[ad_1]

I was 50 years old when I bought my first drone. It required me to learn a whole new set of skills not only in flying and navigating a UAV but also in learning new photographic and video techniques for my eye in the sky.

That was 2017 and last month I was 58 years old. But do you know what? I am still learning new things about photography. It would be cliched to say I learn something new each day, however I think it’s realistic to say I learn something new about photography every week.

There are two reasons for this. The first is that as photography is my primary source of income, it is important for me to keep ahead of new things. The second is the pace of change in photography – and indeed all technology – is phenomenal. It’s both exciting and scary.

Today we are going to delve a little deeper into this and look at why you are never too old to learn new things photography.

The Exponential Curve

My first camera, as some of you will know, was a Zenit 11. It was bought for my 16th birthday way back in 1984. It had zero automation, manual exposure, manual focus, manual metering and of course shot film. My camera as of today is a Sony A7Rv, it’s automatic everything, packed with technology and of course shoots digital.

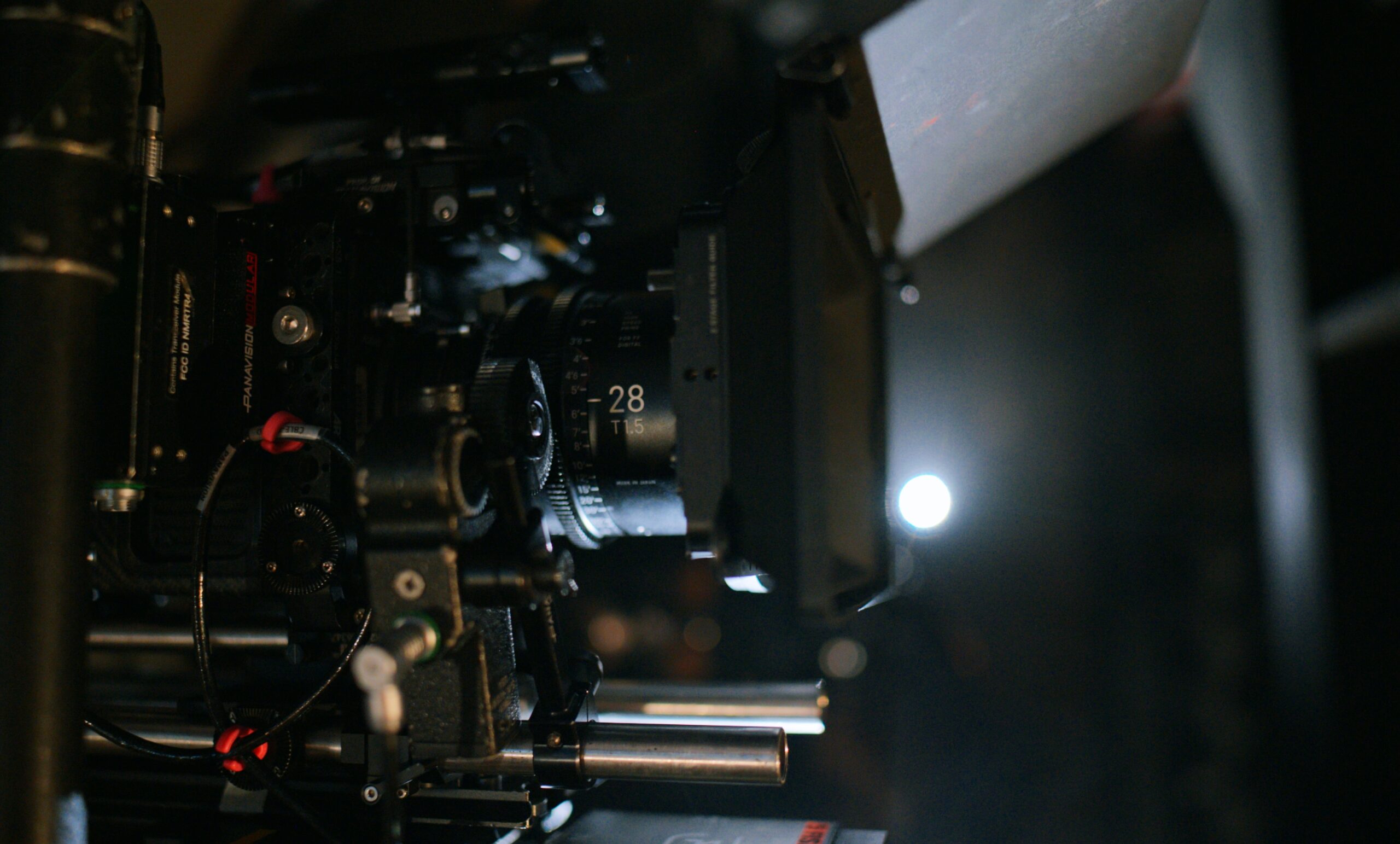

The change between that first camera and my current one has been exponential, so has my learning curve. Whilst the Zenit instilled in me an understanding of shutter speed, aperture, ASA and composition, the Sony has taught me things about AI focusing, the differences in video codecs plus a plethora of other high tech tools that I don’t necessarily need, but certainly would like to know about.

Beyond the actual taking of the image, the way we process those images has changed. My first film on the Zenit went off to Snappy Snaps and came back a week later as glossy 6×4 inch prints. My last “film” on my Sony was uploaded to my computer an hour after I got home, edited in Lightroom and on social media within two hours.

The fact that I could so comfortably upload, edit and publish my images comes from the steep but highly enjoyable learning curve that I undertook right from the very first days of shooting. The keyword is enjoyable.

If You Enjoy Your Photography, You Will Learn

For many of us, photography is not a profession, it’s a pastime. When you use your leisure time to do something, it can feel like somewhat of a chore to learn something new. However, the old phrase, practice makes perfect is not without merit.

The wonderful thing about photography, is that it doesn’t need hours poring over books or watching YouTube videos. All you need to do is get a gist of the new thing you wish to learn about, than simply go out and shoot. The beauty of digital cameras is that we can keep taking shots until we get it right, or until we have learned the technique we wanted.

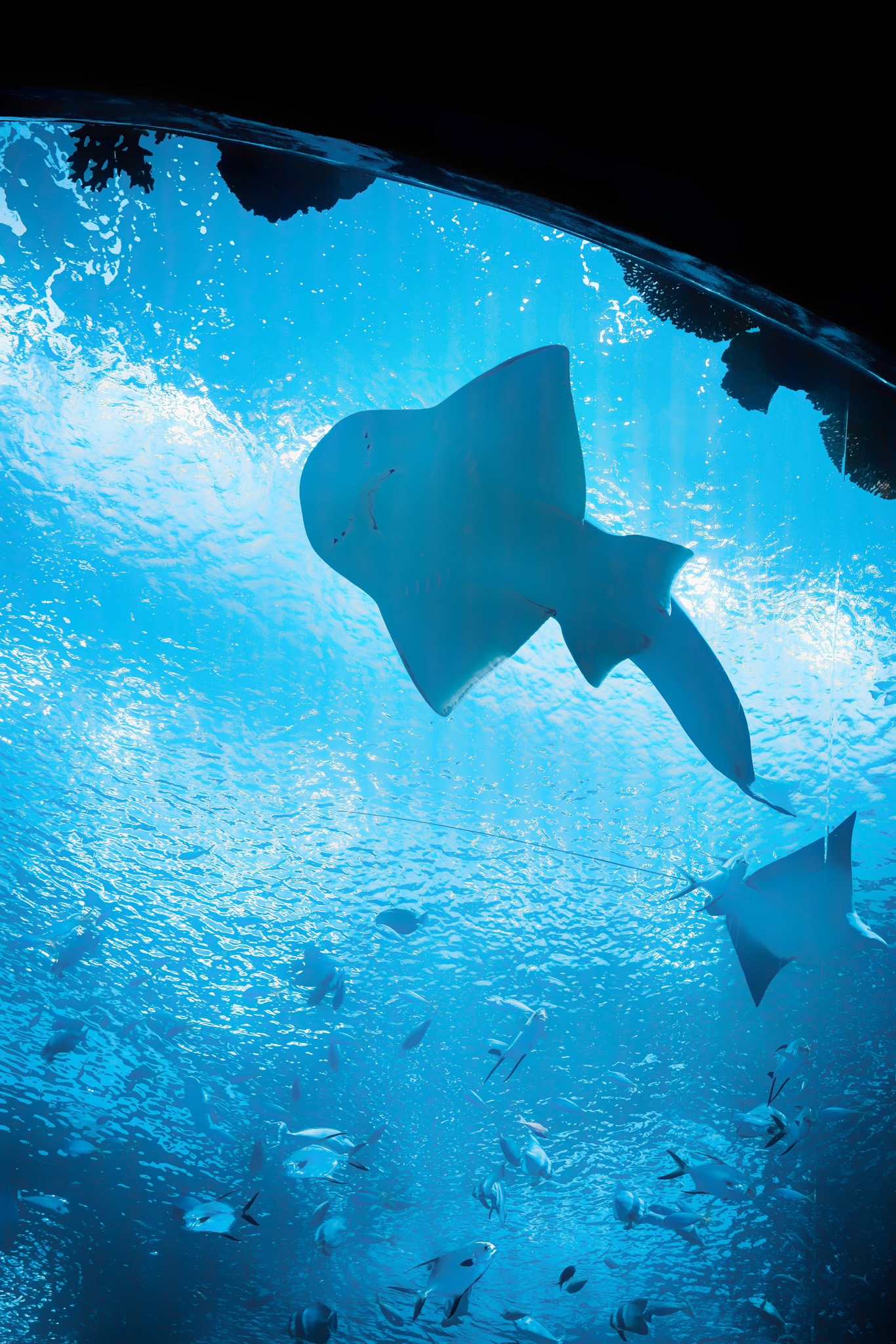

Let’s return to my drone photography. When I first put the drone in the air, the last thing on my mind was taking photos. The main concern was how much this was going to cost me if I crashed. However, within a few flights I found myself enjoying the flying so much that it started to become second nature. So I started to take photos and videos. And you know what? They were awful.

I was at the beginning of a learning curve again. However, the fun factor not only of flying the drone but also of taking photos, drove me on to do better. Slowly, flight by flight, I came to understand the different approaches I would need to take whilst shooting from a drone as opposed to shooting at a fixed location.

My photography improved as did my desire to go out more often with the drone. Incidentally, the biggest mistake new drone photographers make is to take images from maximum altitude. The best shots come from down at mid and low levels. I created a video about that.

The point is that as we all enjoy photography, the learning part of it will come naturally. It doesn’t have to be forced, just go out, practice, practice and practice some more. The end results will keep driving you on to learn more.

Don’t Be Overwhelmed

As I mentioned, the pace of change in photography can seem like it is exponential. That in turn can make you feel overwhelmed at the sheer amount of new stuff you need to learn. Perhaps to a point where you just decide to stay with what you know.

You don’t have to be overwhelmed though. Whilst there are seemingly huge amounts of new techniques and technology that need to be absorbed, some, if not the majority of it may not be relevant to your photography.

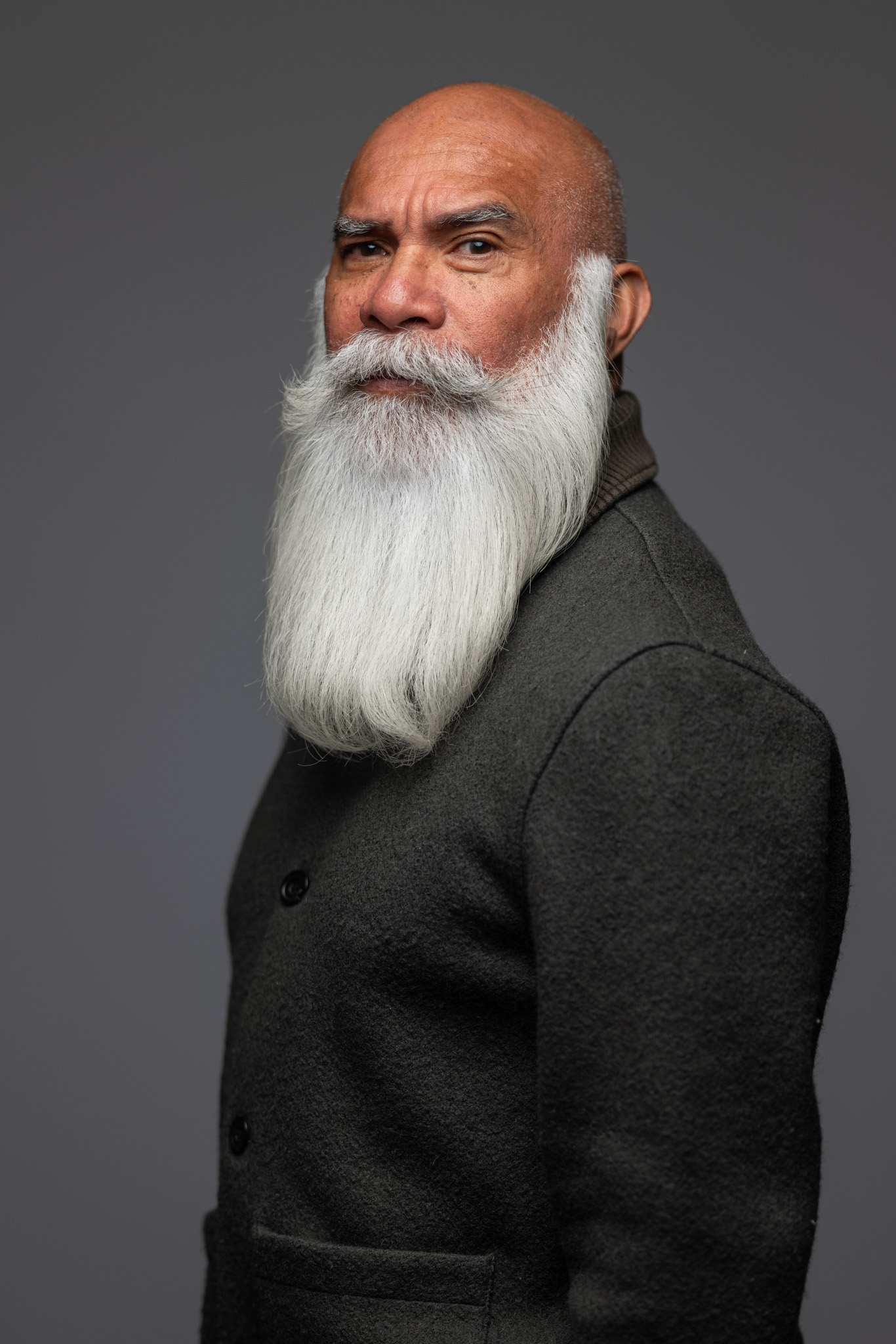

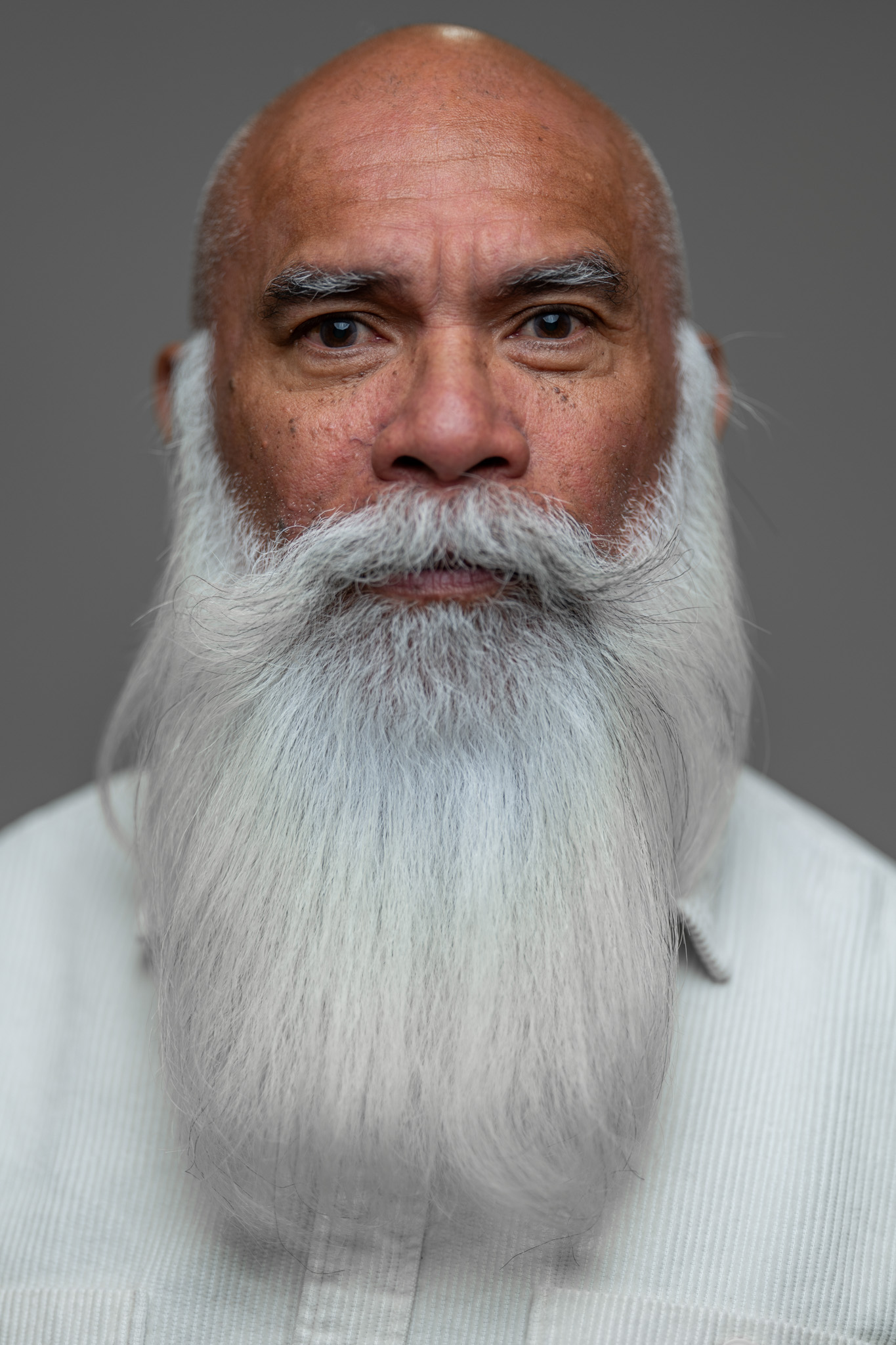

If, for example, you don’t shoot video, any new video techniques, codecs or equipment is going to be irrelevant to you. If however, you are a portrait shooter and a new lighting technique becomes available, that may well be something you want to look deeper into. It’s all about learning the things that will make you a better photographer.

There is another thing to bear in mind, particularly in this short video, TikTok world we live in. That is, viral photographic trends are often just that, trends. They very rarely lead to improved technique or long term betterment of your photography. They are effectively cheap tricks to garner views. Cut this fluff out of your photographic learning process and just concentrate on the information that will improve your creativity.

You’re Never Too Young To Learn

For the bulk of this article I have come at it from the point of an older person. However, I also think many of the things mentioned are as important if not more important to younger photographers. If you are starting your photographic journey today, it is perhaps more vital to try and stay ahead of that ever increasing curve. In the near future, we will have cameras that allow you to change focus and depth of field in editing – we already do with smartphones.

We have the ever increasing encroachment of AI images and with it the moral considerations of using it. The rate of technological change will only increase and with it our potential to be inundated with information that may not be relevant to us.

I would suggest that it’s more important than ever for a younger photographer to experiment with genres, but also to concentrate on one or two they enjoy the most.

Photography is and always will be a lifelong learning curve. Back in the days when I started, it was pretty simple – learn exposure, learn focus and concentrate on composition.

Today, the way we shoot has changed massively and to remain relevant we need to concentrate on learning the things that are most important to our photography. If you can sort the chaff from the wheat, you will find yourself continuing to learn and enjoy your photography.

Further Reading

[ad_2]

Source link