Great product photography doesn’t just make your website look good—it drives clicks, conversions, and customer trust. Whether you’re shooting apparel, jewelry, home goods, or tech, how your products look online directly impacts how well they sell.

But coming up with fresh photo ideas or perfecting your visual strategy isn’t always easy.

That’s why we rounded up 50 ecommerce websites with standout product photography—organized by industry. These examples highlight how top brands use composition, lighting, styling, and editing techniques to elevate their imagery and move more product.

Browse for inspiration. Steal a few ideas. And if you need help turning your own shots into polished product images, we can lend a hand there, too.

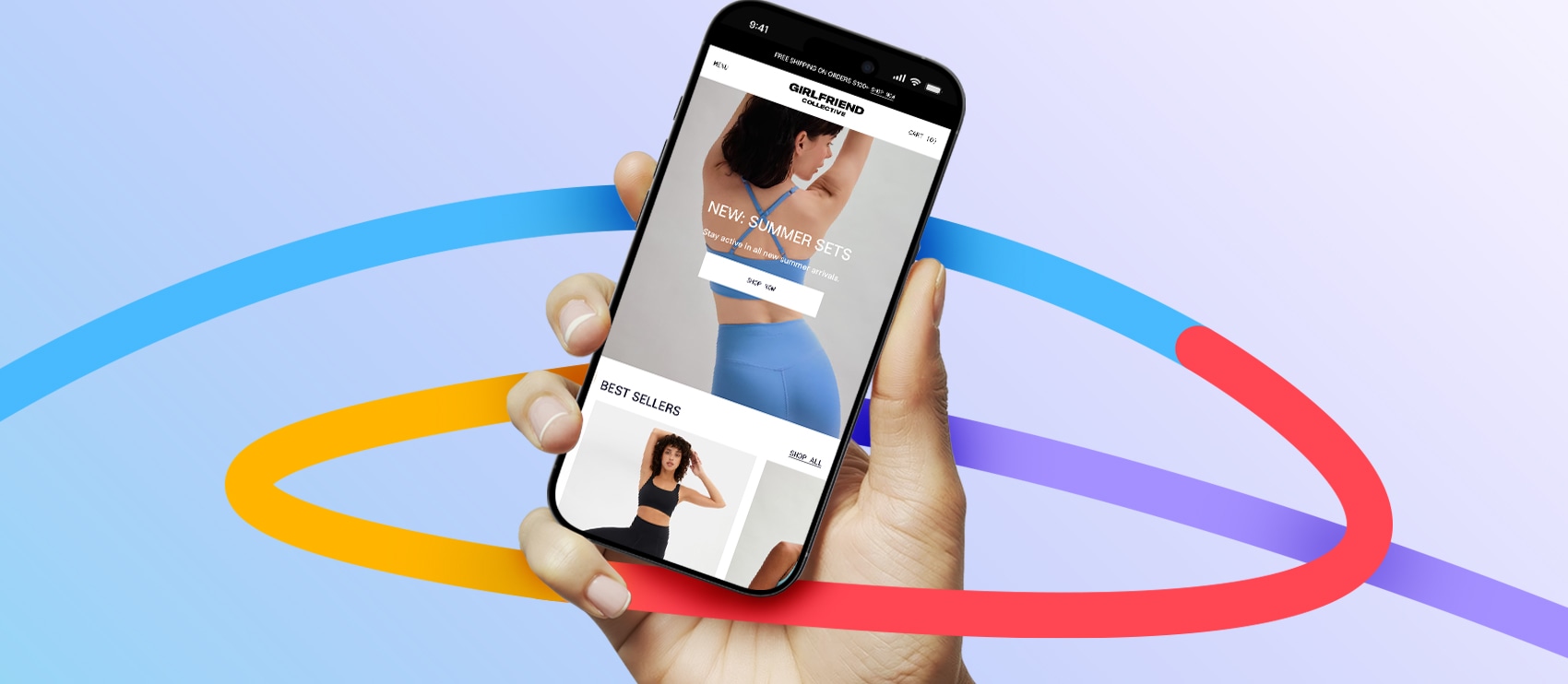

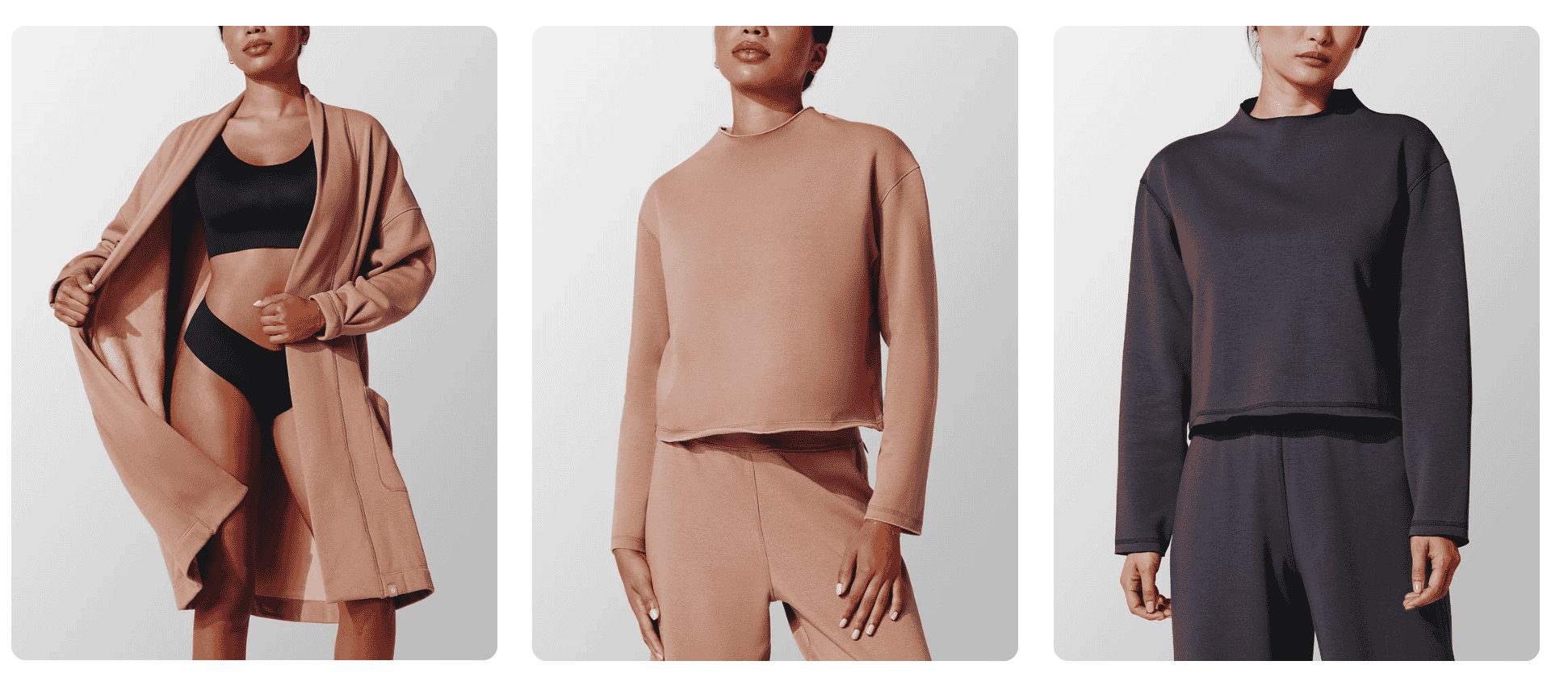

1. Girlfriend Collective

Image source

This set of images features clean, high-resolution portraits of models in active poses, styled against a neutral, seamless background. The garments are front and center, with no distractions from props, textures, or harsh lighting.

This style of photography strikes the right balance between editorial polish and ecommerce clarity—a smart direction for any brand focused on performance, comfort, or versatility.

Start a new order

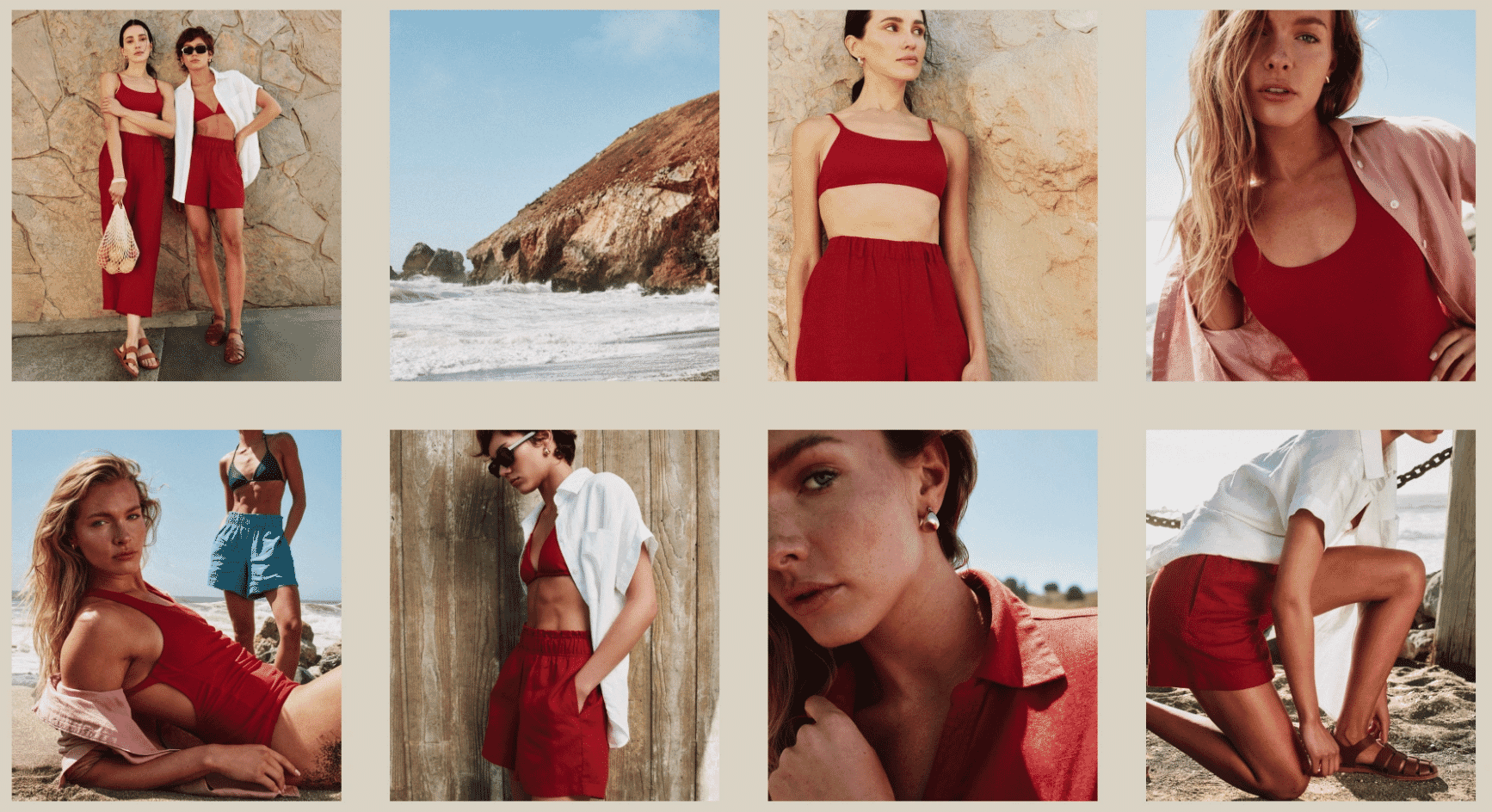

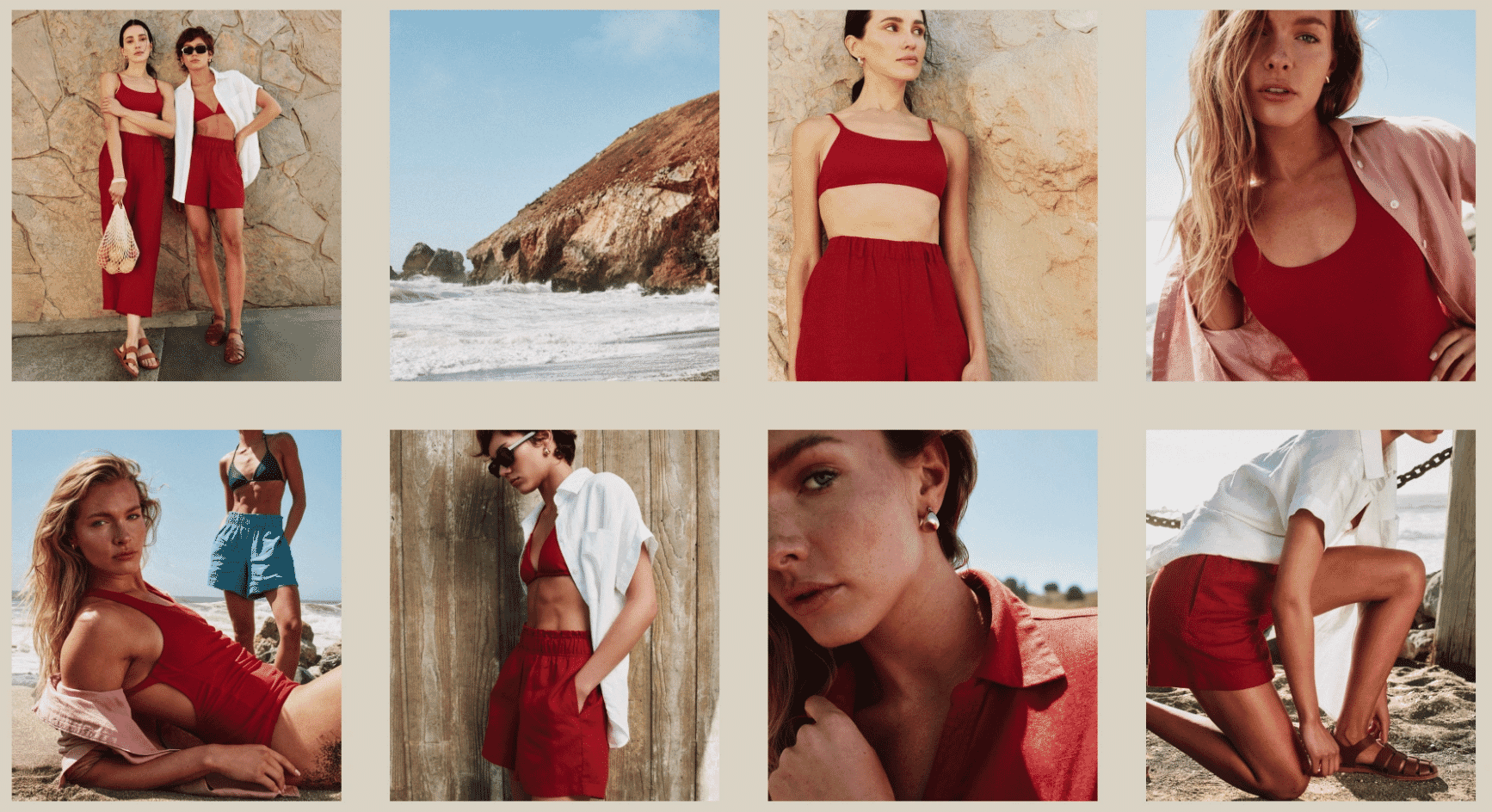

2. Quince

Image source

Quince uses warm, natural light and textured backdrops like stone, sand, and wood) to create a sun-soaked, lifestyle-driven aesthetic. The product photography feels candid and cinematic, blending fashion with storytelling. Clothing is styled casually and captured in movement or relaxed poses, helping customers imagine how pieces feel and function in real life.

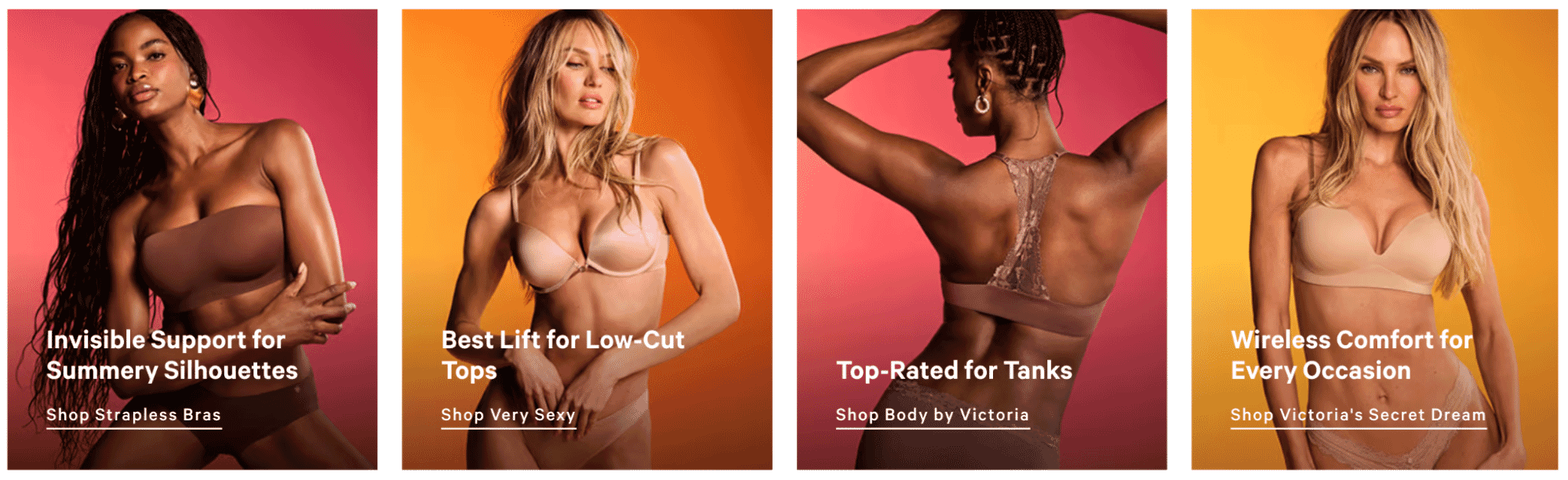

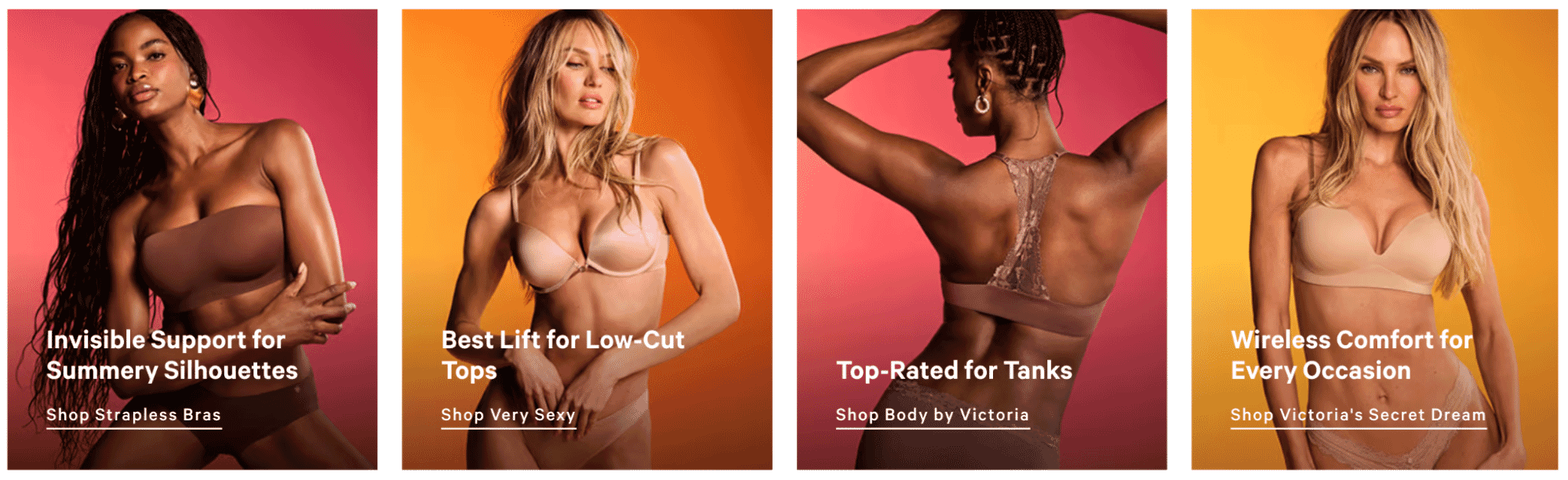

3. Victoria’s Secret

Image source

Victoria’s Secret has secured its spot on the top of the list for product photography for years. It knows how to present their products in a way that speaks to its target audience, and even makes more than 20 million people tune into its annual televised fashion show.

4. ModCloth

Image source

ModCloth shows its products on models of different shapes and sizes, showing the versatility of various items and allowing its customers to better predict how it would look on them. It does the same with color variations, too.

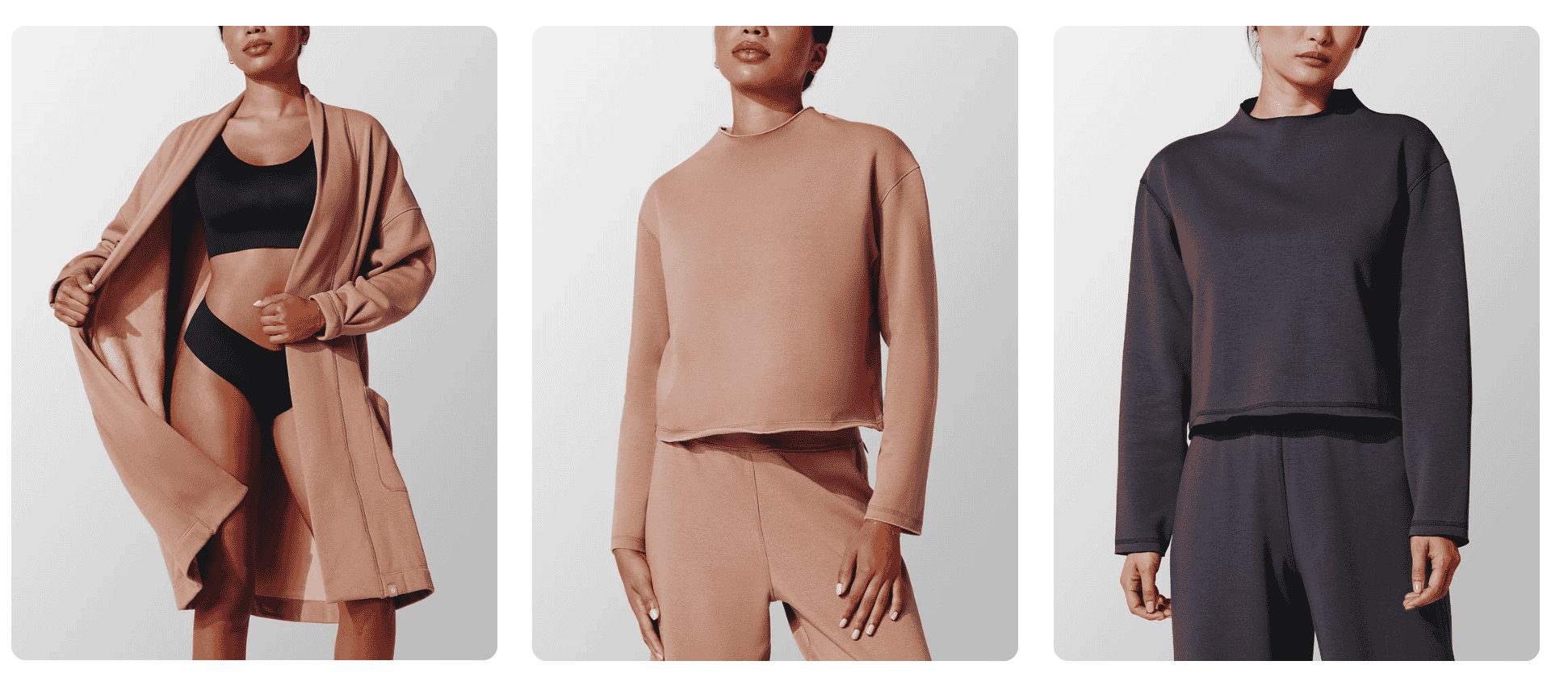

5. Thirdlove

Image source

Instead of using image editing to create color variants for its products, Third Love shoots custom photography for most of the variants. This creates a more lifelike effect that appeals to shoppers.

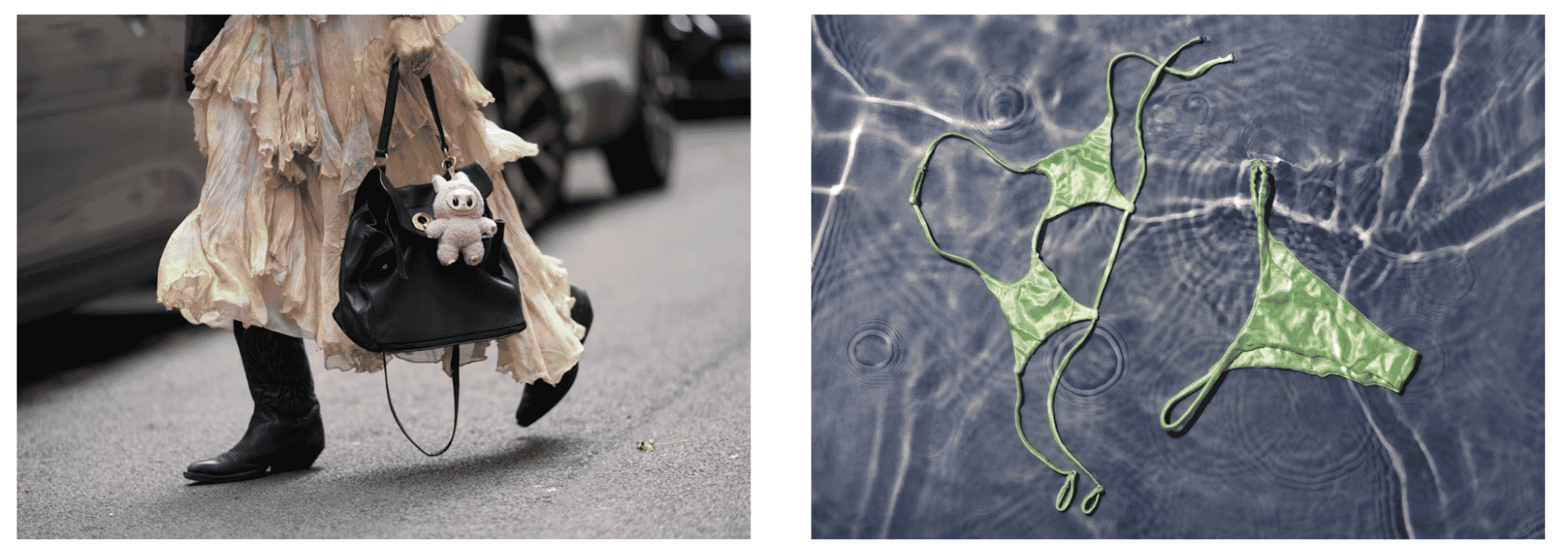

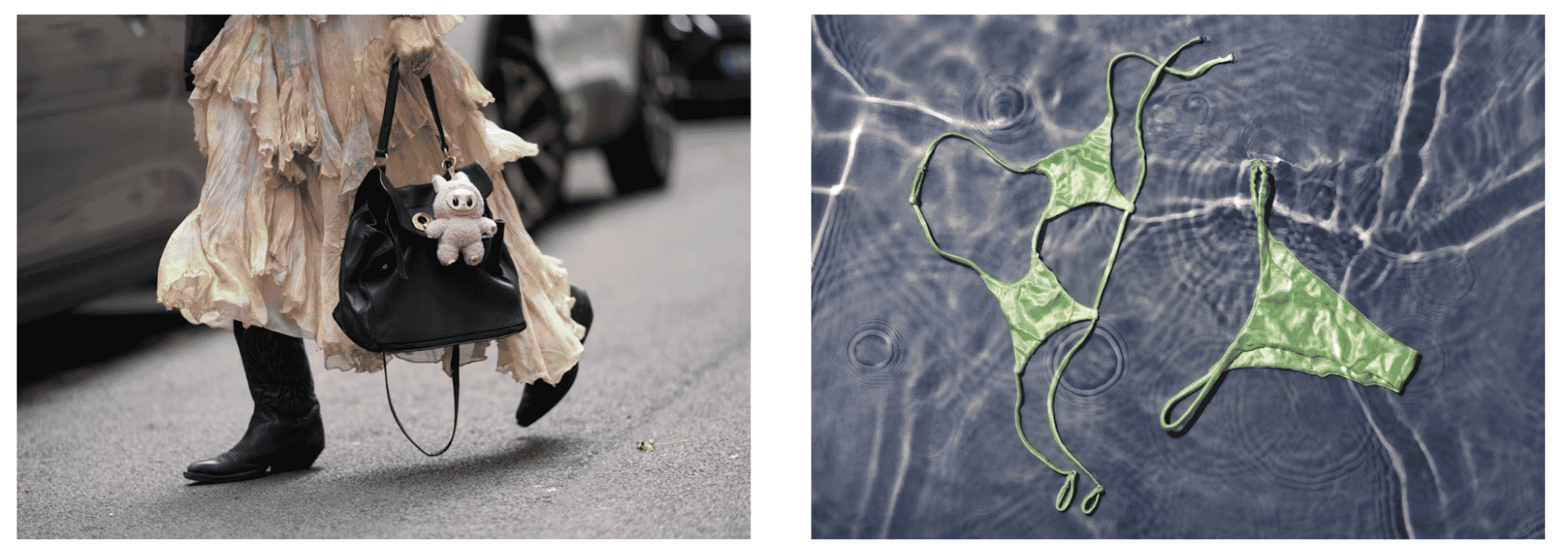

6. SSENSE

Image source

This split-screen from SSENSE showcases the brand’s signature editorial-meets-ecommerce photography style—bold, artistic, and culturally tuned-in.

A street-style inspired shot featuring a flowing, pastel-toned skirt, structured black bag, and plush accessory charm. The blurred background and candid motion capture personality, movement, and context—showing the product in the wild.

The flat lay shows a green bikini submerged just below the surface of a rippling pool. The water distortion and sun reflections turn a simple product shot into an abstract composition. It’s aspirational, seasonal, and emotionally evocative—perfectly suited for a trend-forward audience.

7. Coterie

Image source

These product photos from Coterie offer a clean, clinical, and elevated aesthetic that aligns with the brand’s premium baby care positioning. Shot against a soft, gradient blue background, the diapers are perfectly centered and isolated—creating a sterile but comforting environment that enhances product trust.

What works well:

- Perfect symmetry and clarity: Both the front and back views are shot with precision and balance, emphasizing shape, texture, and material. This symmetry helps customers understand fit and structure at a glance.

- Soft, diffused lighting: Gentle lighting minimizes harsh shadows and ensures every detail of the diaper—such as the elastic bands, fabric texture, and wetness indicator—is clearly visible.

- No distractions: The minimalist backdrop and absence of props keep the focus entirely on the product, reinforcing a sense of hygiene and quality.

🪞 Symmetry sells—especially in fashion. Learn how perfectly mirrored product photos boost conversions and trust.

Jewelry

8. Deliqa Gems

Image source

Each ring is photographed against a seamless white background, allowing the viewer to focus solely on the craftsmanship, color, and cut. This is essential for high-conversion jewelry ecommerce.

The lighting is soft but directional—eliminating harsh shadows while enhancing gemstone brilliance and gold luster. It’s especially effective for faceted stones, making them pop with fire and depth.

Deliqa shows different angles—front, top-down, and profile views, giving online shoppers a true-to-life sense of scale and form, mimicking an in-store experience.

Retouching is used judiciously: reflections are polished, shadows are uniform, and every gem is color-corrected for maximum vibrancy.

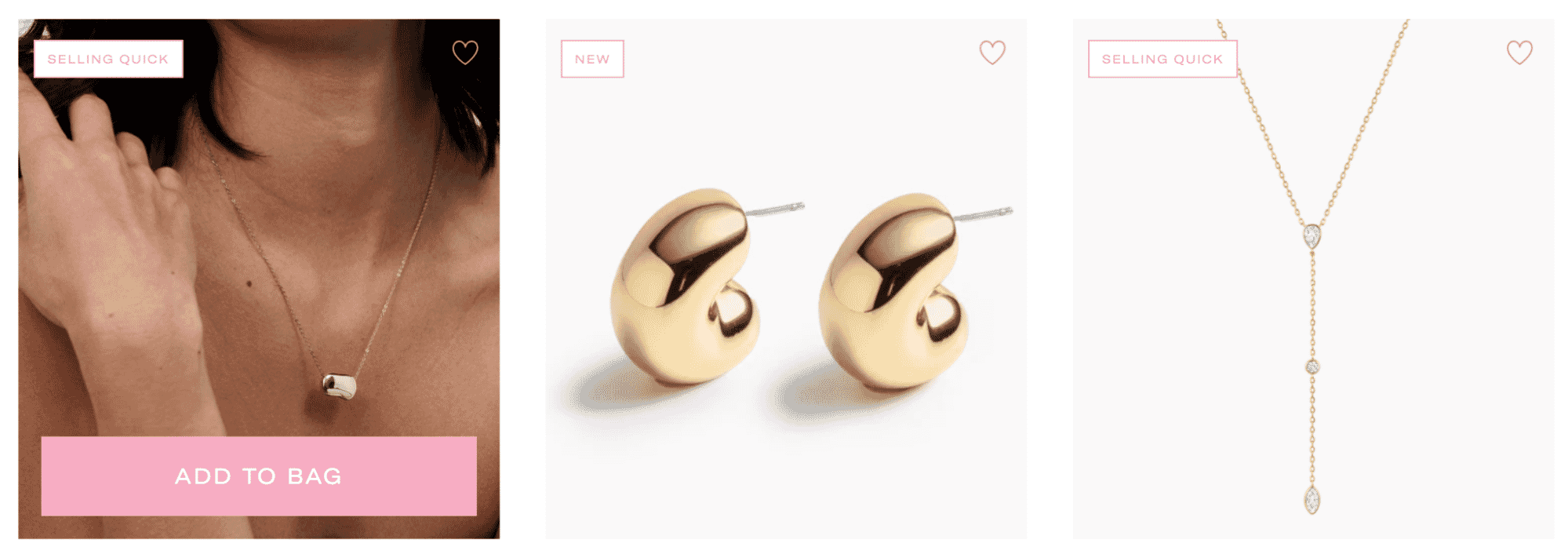

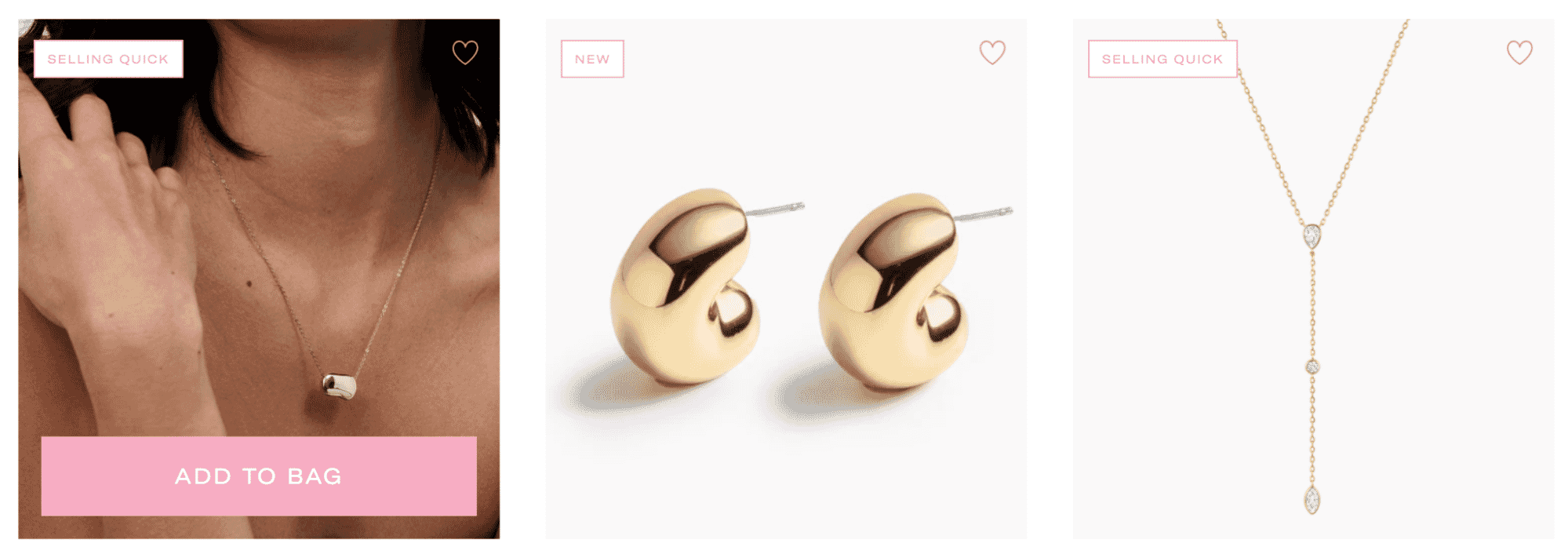

9. Electric Picks

Image source

Electric Picks’s jewelry product photography strikes a perfect balance between lifestyle and studio shots—an ideal approach for modern ecommerce. The left image shows the necklace worn on a model, adding context, warmth, and emotional appeal. The other two are clean studio shots that focus on detail and form. This blend helps shoppers envision the item both in real life and up close.

All three images use natural-looking, diffused light that avoids harsh reflections (a must for shiny metals like gold). The earrings in particular benefit from soft-edged shadows that give them dimension without distraction.

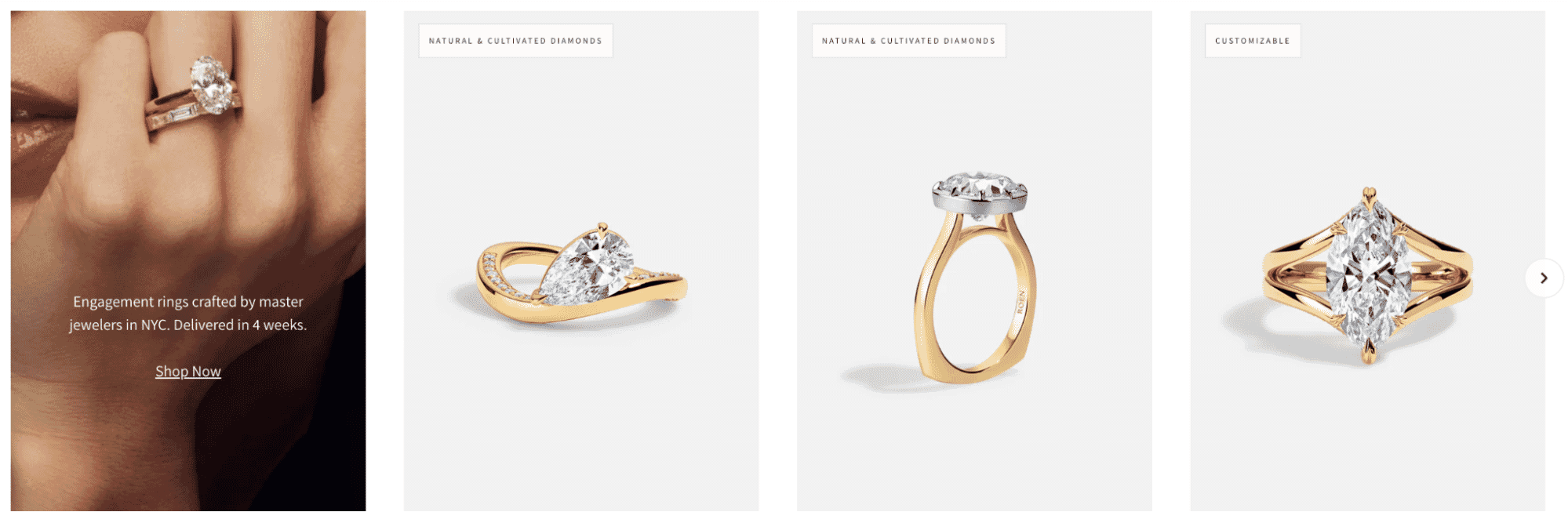

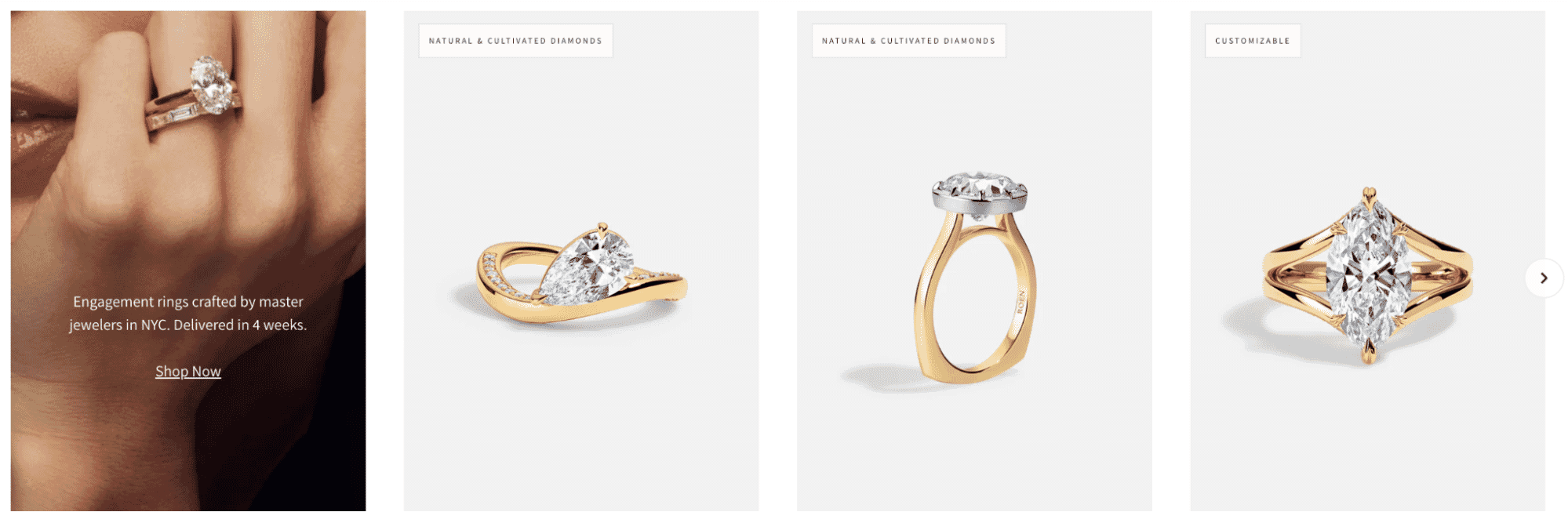

10. ROEN

Image source

ROEN’s jewelry photography example delivers a premium, high-end aesthetic that aligns with luxury engagement ring shopping—balancing emotion, clarity, and craftsmanship.

The leftmost image shows the product on a hand in warm, soft lighting, immediately evoking romance, elegance, and aspiration. It adds emotional weight to the otherwise clinical product lineup.

The remaining three images showcase the rings against clean, light-gray backdrops with subtle shadows that lift the products off the page. Each shot is expertly lit to maximize sparkle, metal luster, and form—especially in the center stone.

Side views, angled shots, and direct front views all help customers evaluate details like band thickness, setting style, and stone cut.

11. Susan Alexandra

Image source

This playful product photo brilliantly blends creativity and humor to showcase a beaded dog leash set. The real dachshund and its beaded twin—linked by matching rainbow leashes—instantly grab attention and make the image unforgettable.

This image is a strong example of how injecting personality and playfulness into product photography can make a brand stand out—especially for fun accessories.

12. OUTOFOFFICE

Image source

This set of product photos uses clean styling and close-up detail to showcase modern jewelry in a minimal, elevated way. Each frame focuses on a different piece—earrings, rings, bracelets, and necklaces—while keeping the background simple and distraction-free.

This style is ideal for luxury, designer, or minimalist brands that want to convey sophistication and clarity in their product presentation.

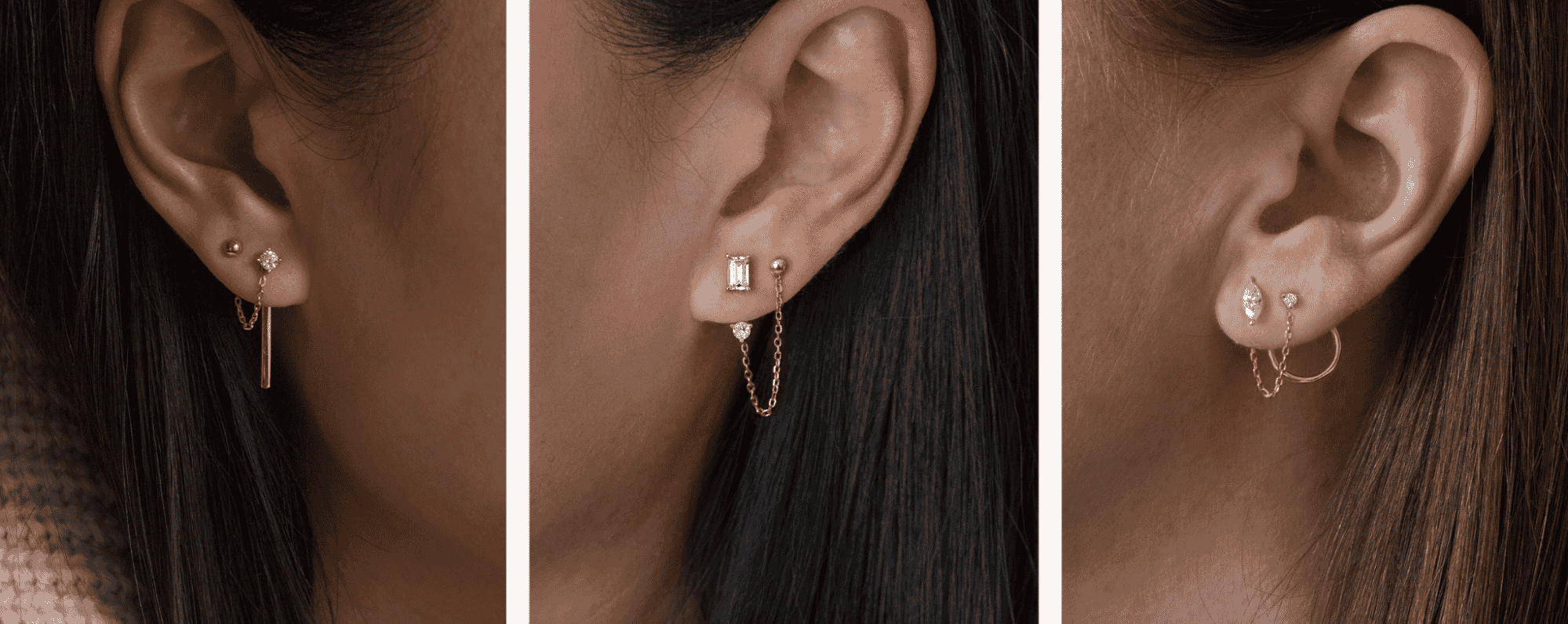

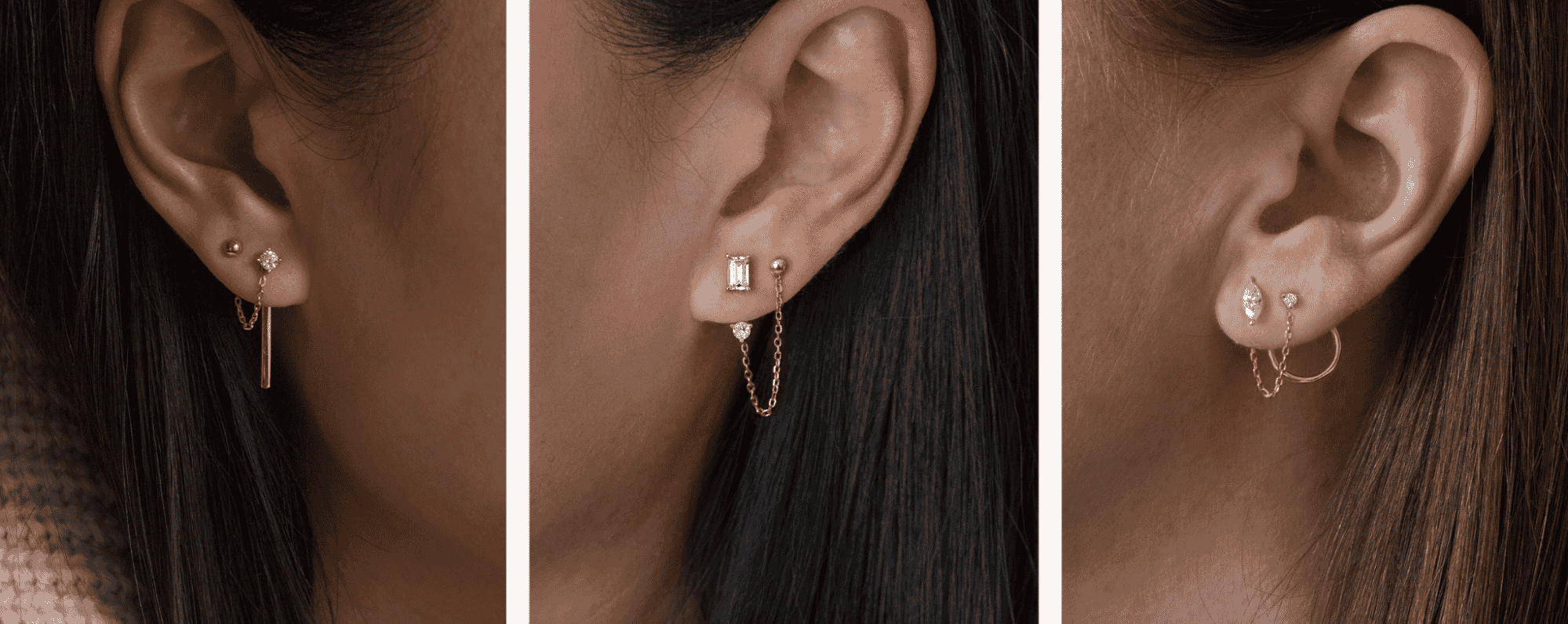

13. Jewels & Aces

Image source

This series of close-up earring shots exemplifies how subtle styling and soft lighting can elevate small, intricate jewelry. Each image highlights a layered ear stack featuring dainty gold chains and diamonds, worn in unique yet coordinated pairings.

Here’s what we like:

- Warm, natural light: The lighting enhances the gold tones and gemstone sparkle without harsh shadows.

- Tight framing: Zoomed-in ear shots keep the focus on detail, allowing customers to see how each piece fits and drapes.

- Consistent tone: The cohesive color palette and similar poses across models create a polished, trustworthy brand image.

💍 Want your jewelry shots to sparkle like ROEN or Electric Picks? Learn the secret techniques for high-converting images in our expert guide: How to Edit Jewelry Product Photos Like a Pro

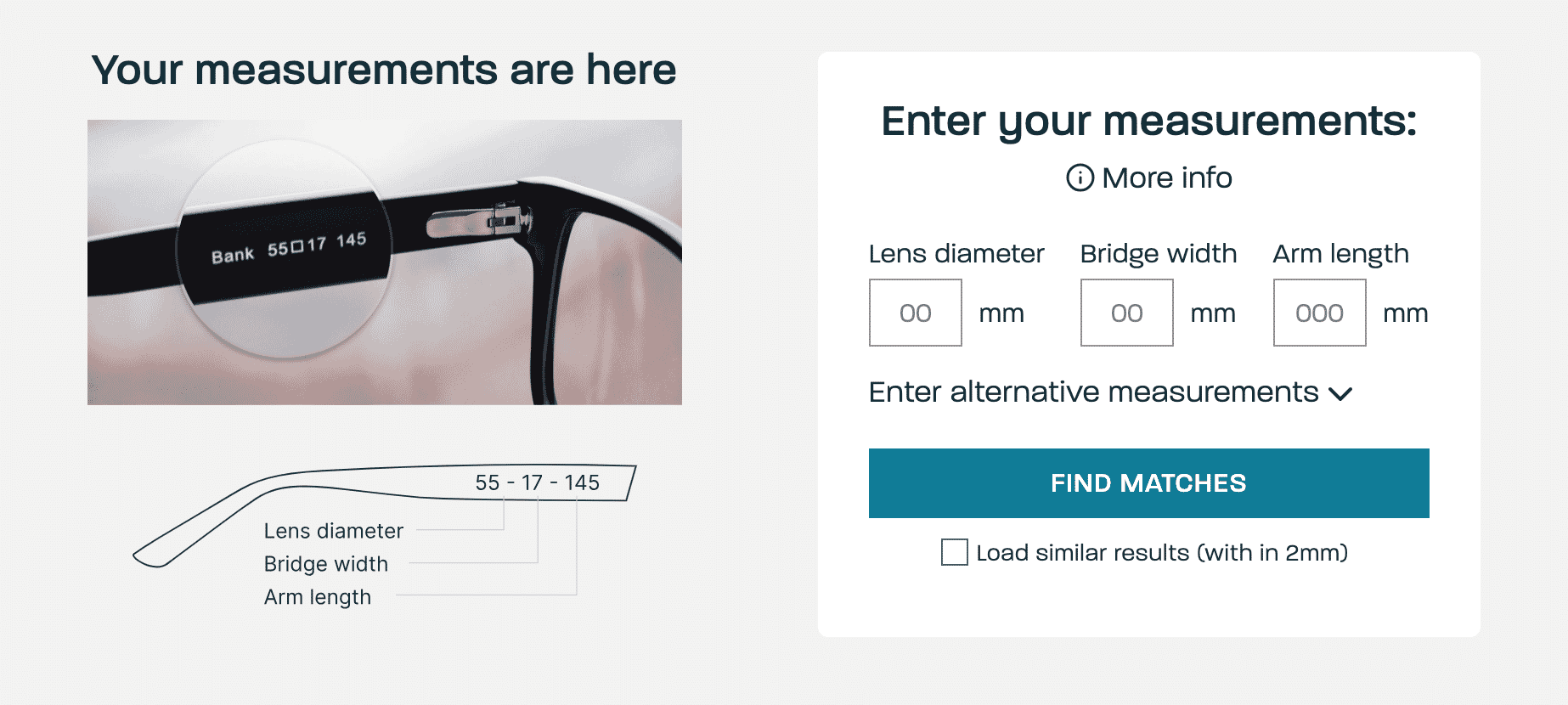

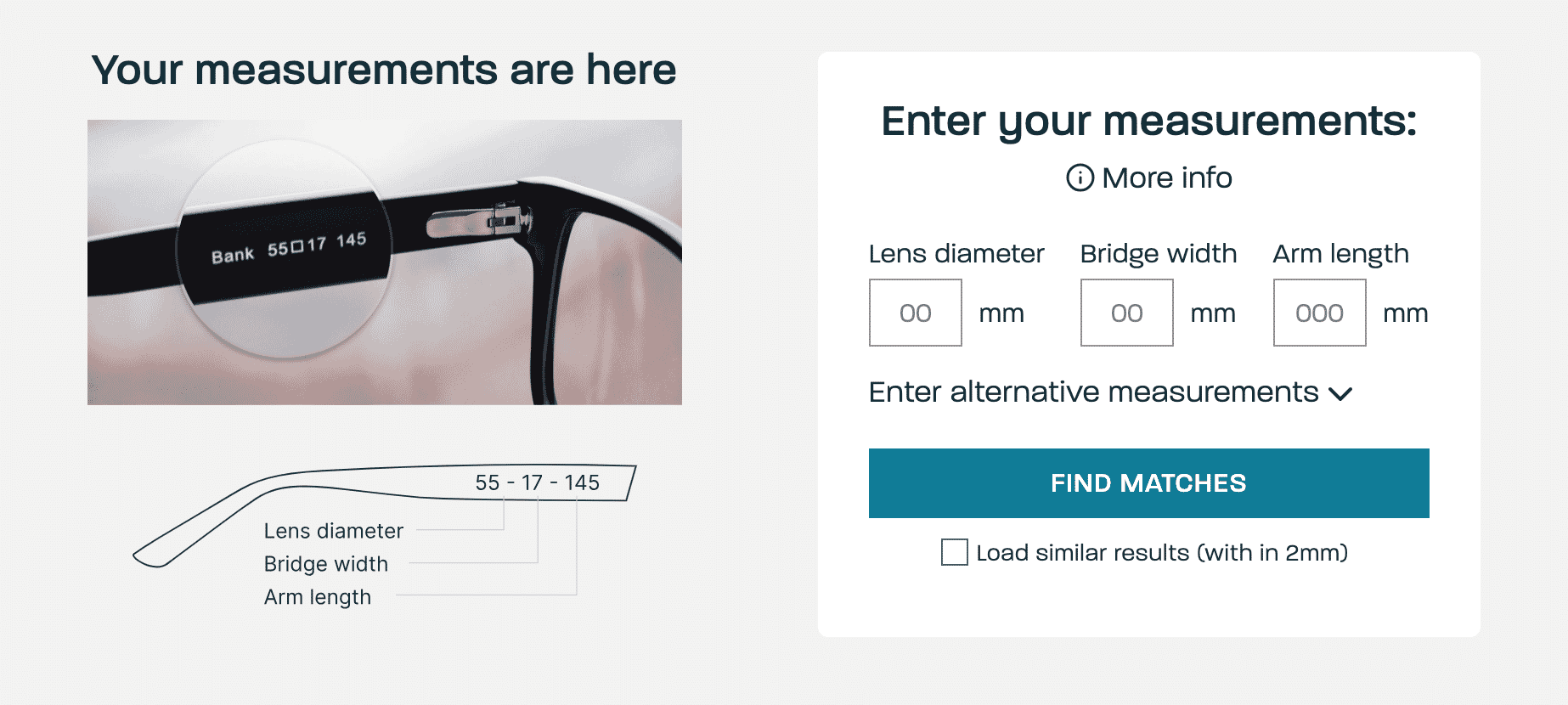

14. Glasses Direct

Image source

While Glasses Direct has straightforward yet beautiful white background product photos, supporting visuals round out the impact for potential customers. Illustrations that outline dimensions help shoppers estimate how the frames would fit on their own faces.

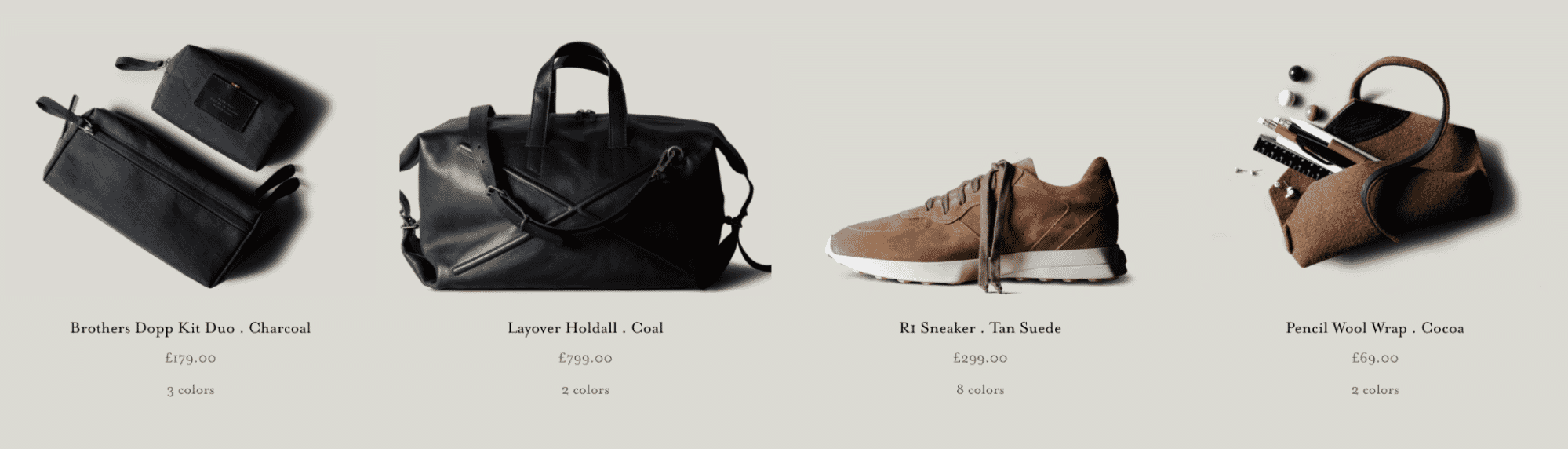

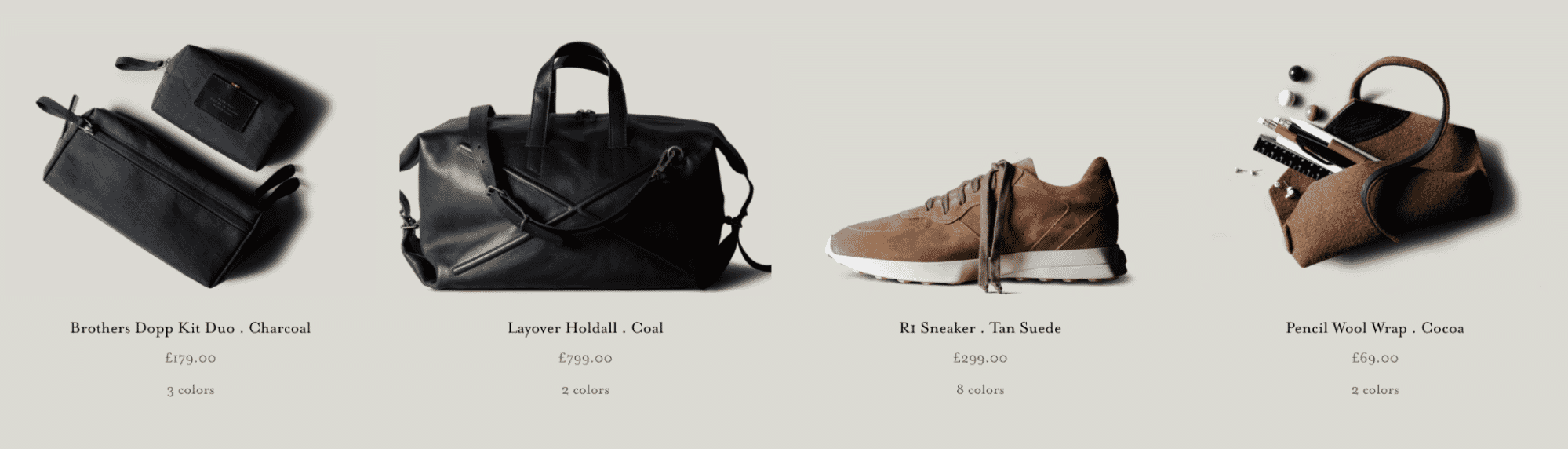

15. hardgraft

Image source

With a muted, desaturated palette and soft directional lighting, each item is photographed with studio precision against a neutral background. hardgraft’s deliberate use of shadows adds depth and dimension without distraction, allowing the tactile richness of suede, leather, and wool to take center stage.

The styling is minimal but intentional—products are cleanly isolated yet carry subtle lifestyle cues, like an unzipped kit or a pencil-stuffed wrap. This clean and cohesive look highlights craftsmanship and quality, appealing to discerning customers who appreciate quiet sophistication.

16. Mulberry

Image source

This campaign showcases handbags in vibrant, outdoor settings that feel both editorial and approachable. Rather than sterile studio shots, these lifestyle images embed the bags into real-world fashion moments—making them feel aspirational yet accessible.

Each look is styled to suggest a narrative—countryside strolls, spring fashion—adding depth and relatability to the product. Shooting outdoors brings out texture and color in the bags, while the blooming florals and tree-lined road evoke seasonal charm. Bold outfits and confident poses draw attention, but the handbags remain the focal point, always held prominently and clearly lit.

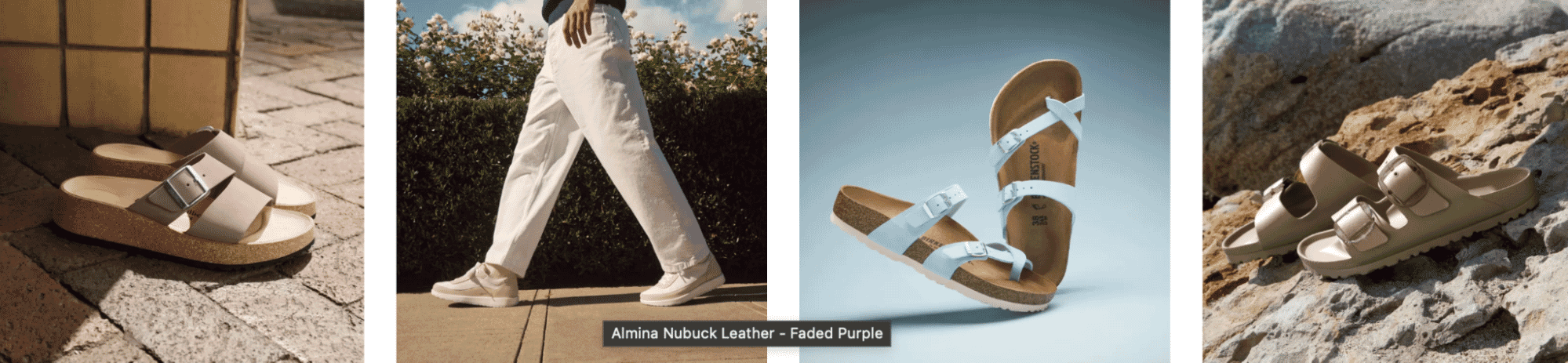

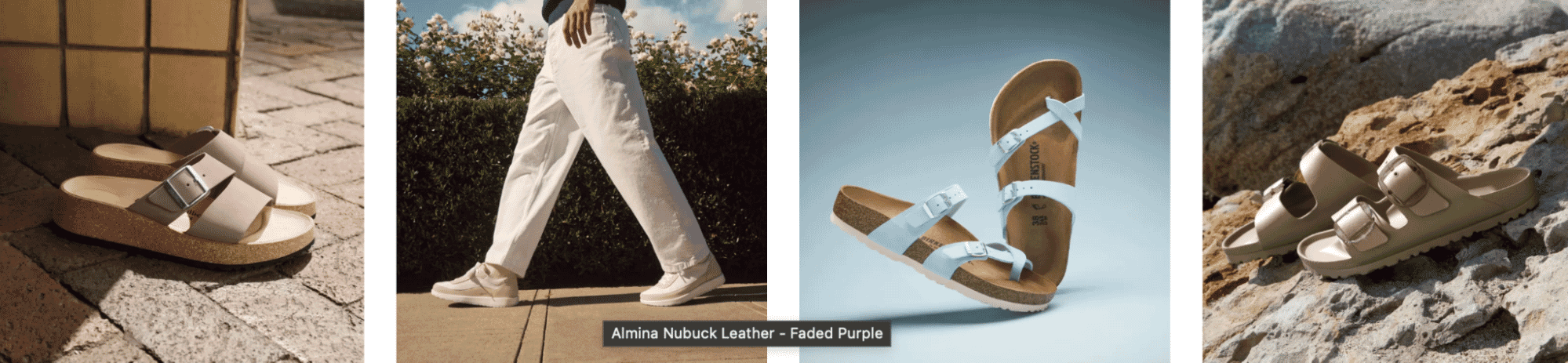

17. Birkenstock

Image source

Birkenstock’s product photography strikes a balance between lifestyle and studio visuals. From sun-drenched sidewalk shots to clean, floating product images, each photo highlights the brand’s signature comfort and craftsmanship. The use of natural textures—brick, stone, and foliage—adds warmth and tactility, making the sandals feel at home in any setting.

Meanwhile, crisp lighting and soft shadows emphasize material quality, like nubuck leather and contoured cork soles. Their floating product shot, set against a cool gradient background, draws the eye to every strap and buckle with sculptural clarity. Birkenstock’s visuals are proof that even casual footwear can look iconic with the right photography.

18. Chalo

Image source

This image series presents handcrafted leather boots through a rich visual narrative that blends craftsmanship, product detail, and styling. From top-down flat lays to styled shots and macro textures, it balances artistic flair with product clarity.

Warm, earthy hues echo the natural materials and craftsmanship, making the entire set feel cohesive and tactile. Including the artisan’s hands working on the leather gives authenticity and emphasizes the handmade quality—connecting product to maker.

Technology

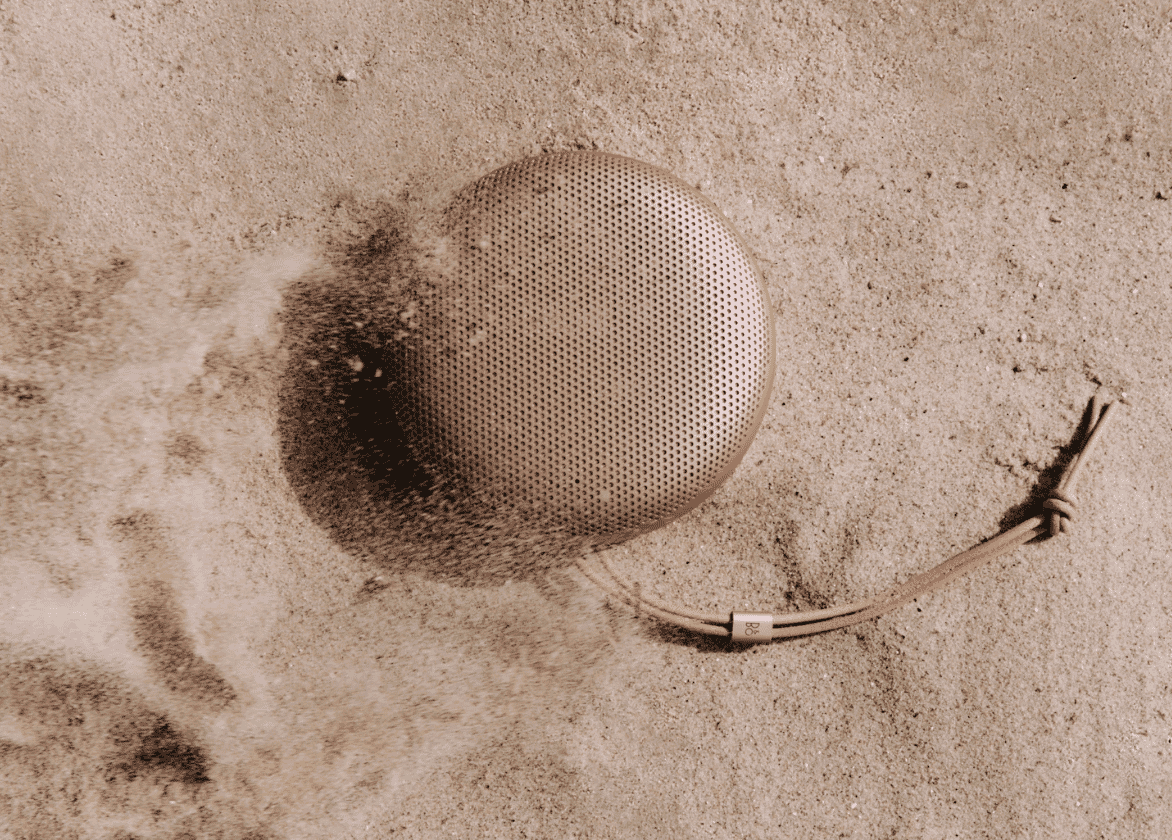

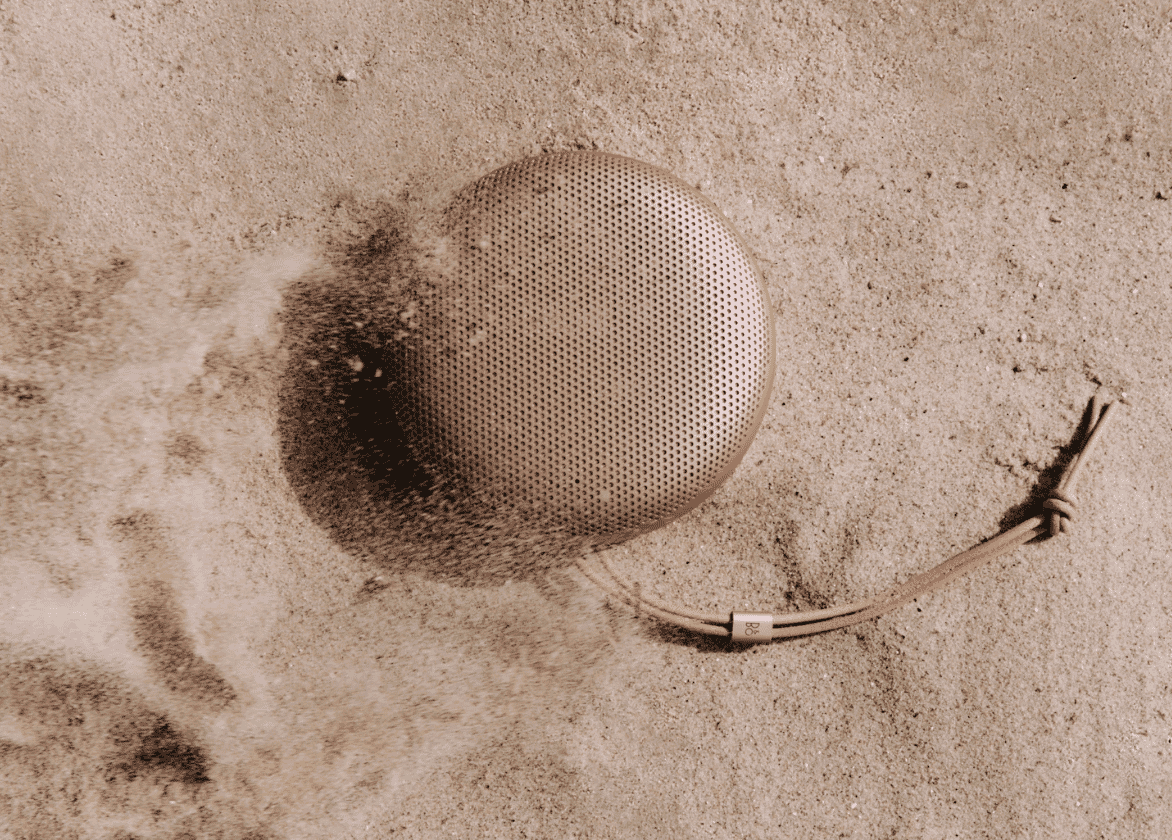

19. Bang & Olufsen

Image source

This photo is a stellar example of minimal, lifestyle-oriented product photography that speaks volumes without clutter—a highly effective way to market portable tech like Bluetooth speakers.

Shooting the speaker partially buried in sand immediately communicates durability, portability, and outdoor utility—perfect for beach days or travel. Plus, the fine mesh texture of the speaker contrasts beautifully with the rough, grainy sand, drawing the eye directly to the product.

The subtle motion blur of sand being brushed aside adds energy and realism, reinforcing the “on-the-go” lifestyle. And the soft pinkish-gold tone of the speaker and tan leather strap blend seamlessly with the neutral sandy palette, creating a warm, aspirational tone.

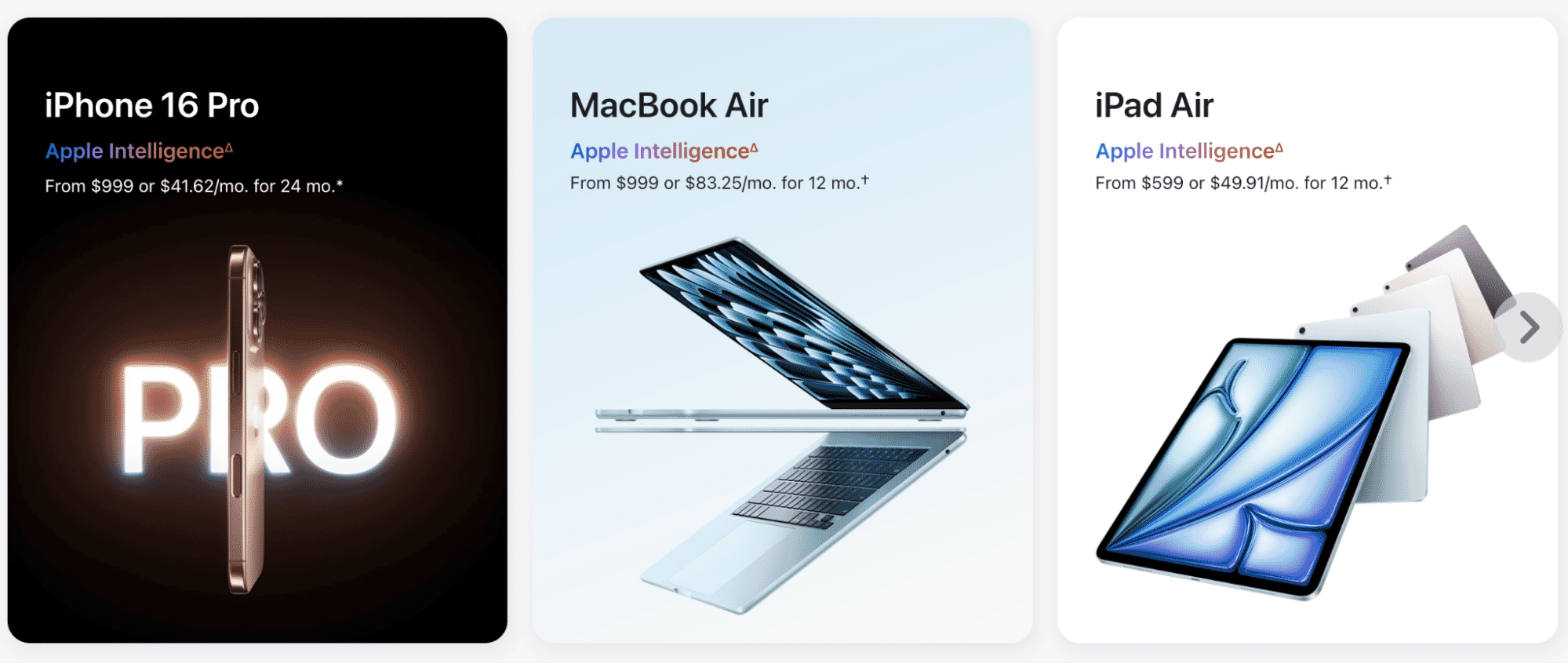

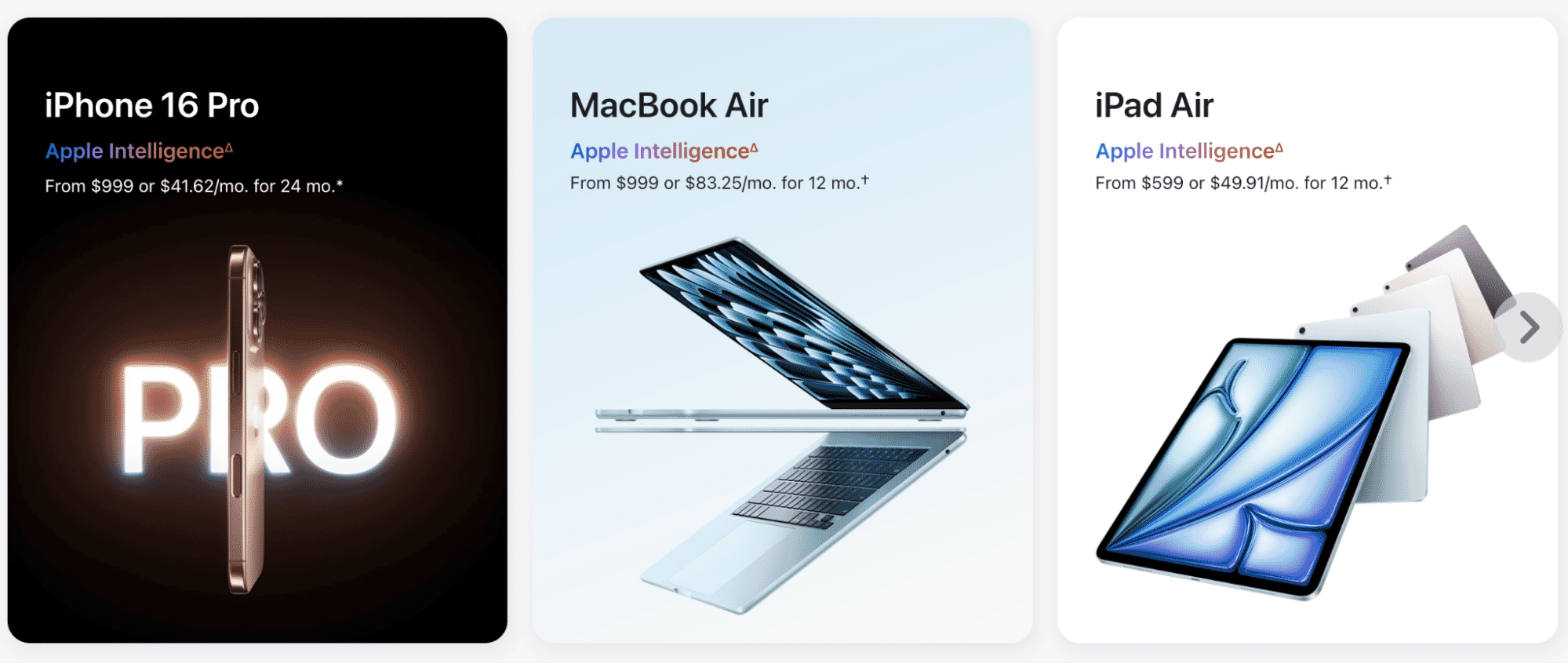

20. Apple

Image source

The iconic tech brand has made smartphones, computers and other tech devices look sexier than ever. The brand has such a strong visual aesthetic, and all product photos support that image—including photos on its distributors’ sites.

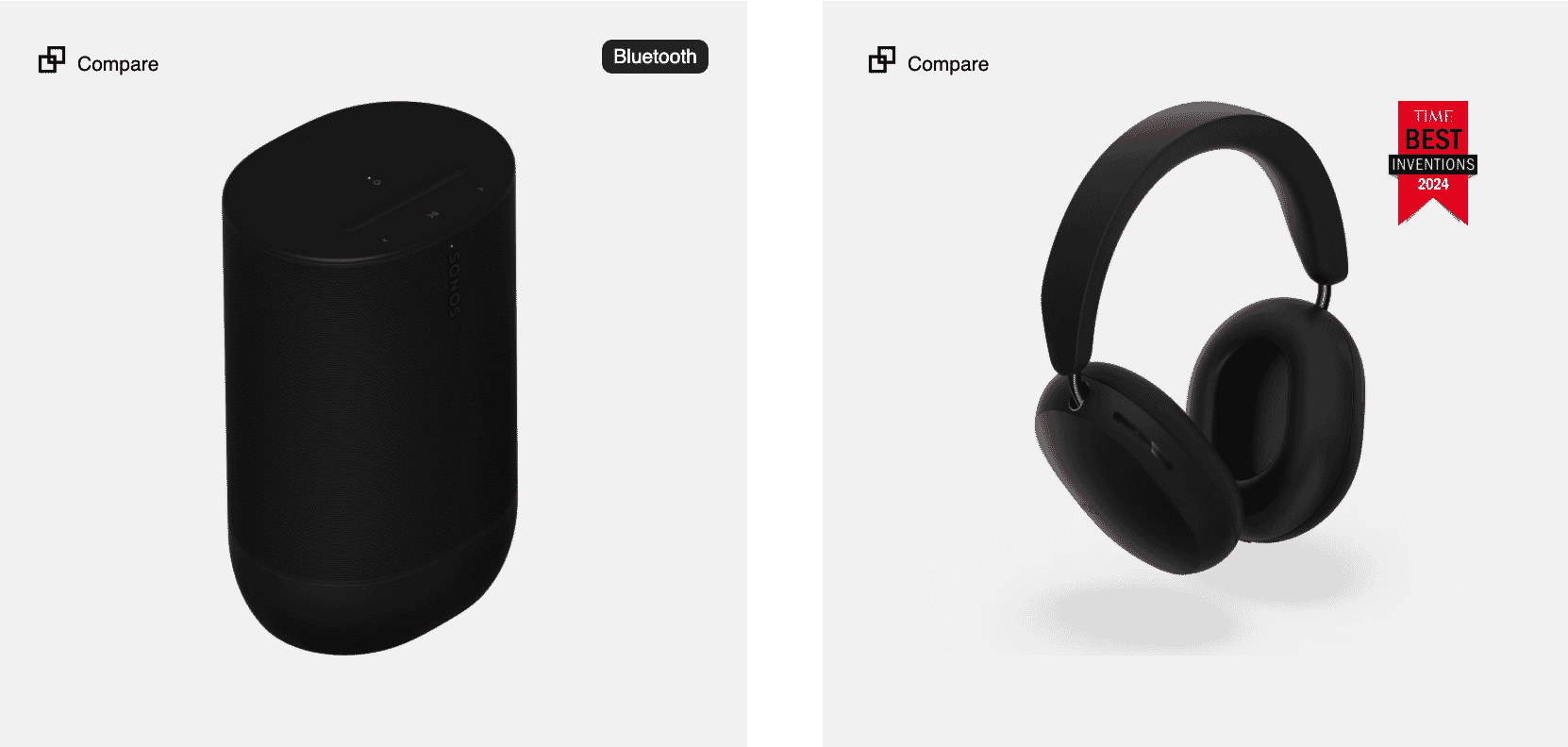

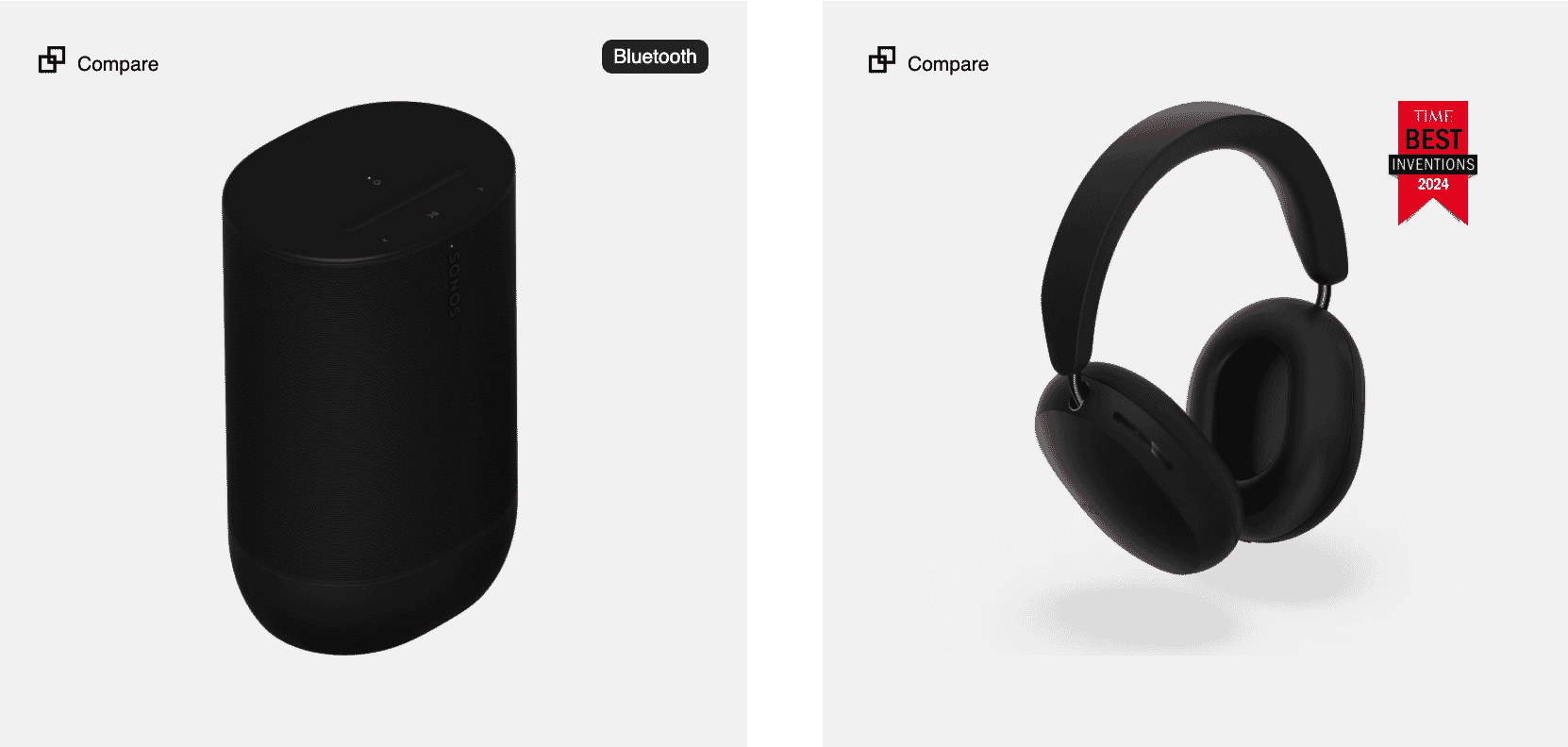

21. Sonos

Image source

This image from Sonos showcases a Bluetooth speaker and a pair of over-ear headphones in a highly polished, product-centric style that’s ideal for ecommerce and tech retail. The clean, white background removes all distractions, keeping the focus entirely on the product design—perfect for a high-end tech brand.

Subtle drop shadows under both products add depth and dimension, helping them stand out while maintaining a crisp, modern aesthetic. The matte black finishes are lit specifically to highlight contours without losing the rich, dark texture—key for showcasing premium materials.

Plus, including the TIME Best Inventions 2024 badge for the headphones subtly reinforces credibility and innovation without overwhelming the visual.

Beauty, cosmetics, and skincare

22. Max Factor

Image source

The bright white backdrop keeps all the focus on the products and makes the colors pop. It’s also super consistent, which is great for brand identity and gives everything a polished, high-end vibe.

Each product is facing forward in a clear, easy-to-identify way. No weird tilts or artsy shadows—just straightforward, scroll-stopping clarity. You immediately know what’s what: foundation, mascara, lip color, and an eyeshadow palette.

Max Factor doesn’t just show product containers:

- The lip color shows the wand and box.

- The mascara is open, showing the brush (which is a key selling feature).

- The eyeshadow palette is open to show the actual shades.

Basically, the photos answer the unspoken “But what does it look like inside?” question before you even have to ask.

23. Essie

Image source

This photo nails the vibe. The mix of bright turquoise, fiery red, and cheery yellow nail art really pops against the warm-toned background. It draws your eye to the nails without needing a spotlight. Each nail tells a mini story—smiley face, abstract flames, a playful “X”—making it feel custom, not cookie-cutter. This is less “salon menu,” more “expression in progress.”

And you get more than just the nails. The texture of the fabric, the paintbrushes, the speckles—it adds a sense of realness and movement, like we just walked in on an artist mid-project.

24. Wiselands

Image source

Wiselands uses rich, moody lighting to elevate its product photography, giving skincare essentials a luxe, tactile presence. The close-up shots highlight the amber glass packaging and gold typography, with warm shadows that enhance the sense of calm and care. Subtle skin contact and soft textures create an intimate, grounded feel—perfectly suited for a brand focused on clean, conscious ingredients.

The lighting is deliberately imperfect, mimicking golden-hour warmth that flatters both the product and the skin it’s meant for. It’s a masterclass in using tone and minimalism to communicate trust and quality.

25. Crown Affair

Image source

The minimalist layout and monochrome color palette for Crown Affair’s product photos ooze luxury. It’s giving calm confidence without shouting for attention.

Each product is centered, evenly lit, and spaced the same—perfect for a sleek grid or product catalog. Cohesion like this builds brand trust fast. And the soft shadows and contrast between black and white bottles add just enough depth to keep things visually interesting without losing the clean aesthetic.

26. Vacation Inc.

Image source

Sunscreen brand Vacation Inc. uses bold, retro-inspired design. The packaging and photo styling lean heavily into a nostalgic ’80s/’90s vacation aesthetic, reinforcing the brand’s identity. Everything from the fonts to the saturated colors supports this.

Despite the vibrant branding, the layout is clean. Products are isolated against a pale gradient background, keeping attention on the packaging.

Outdoors and sporting goods

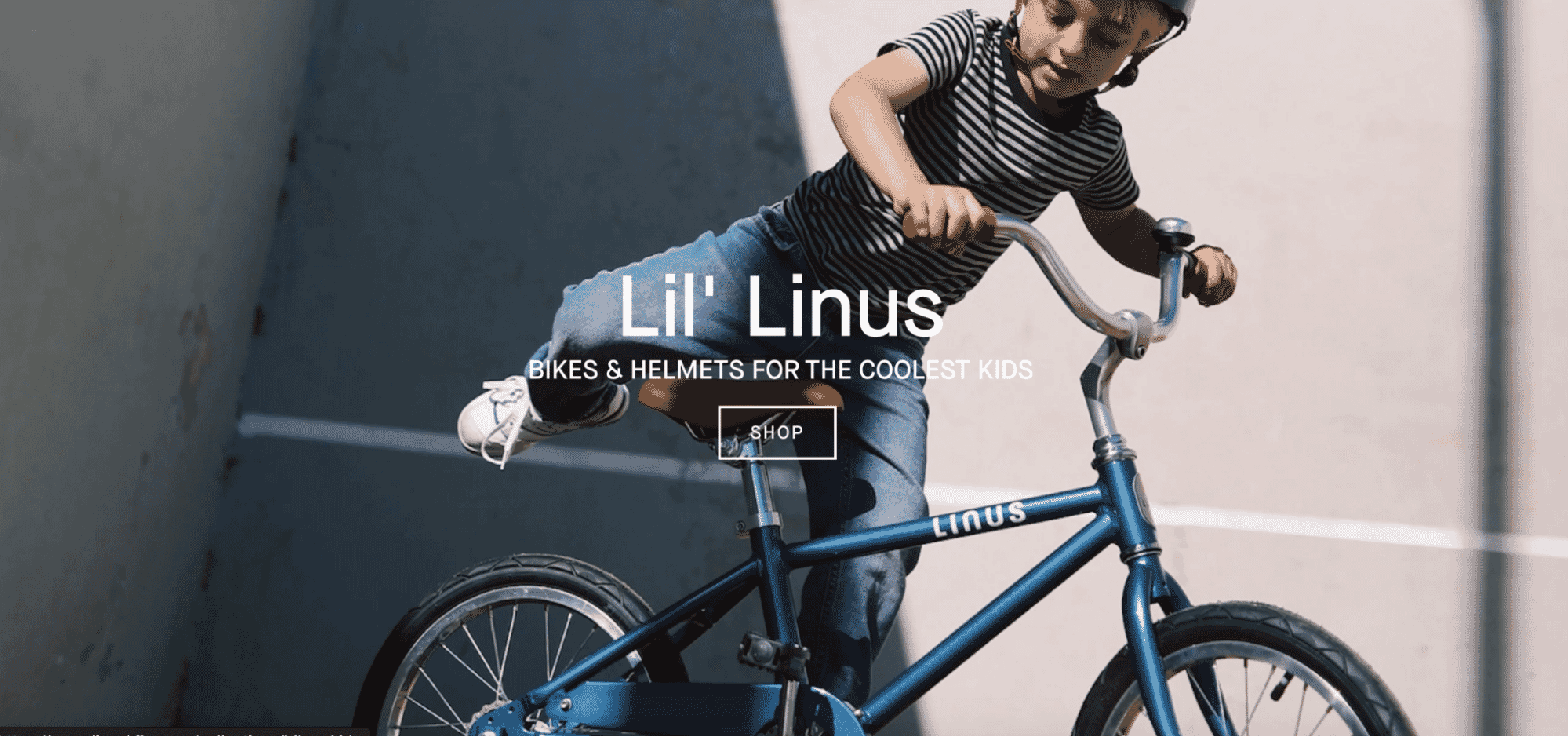

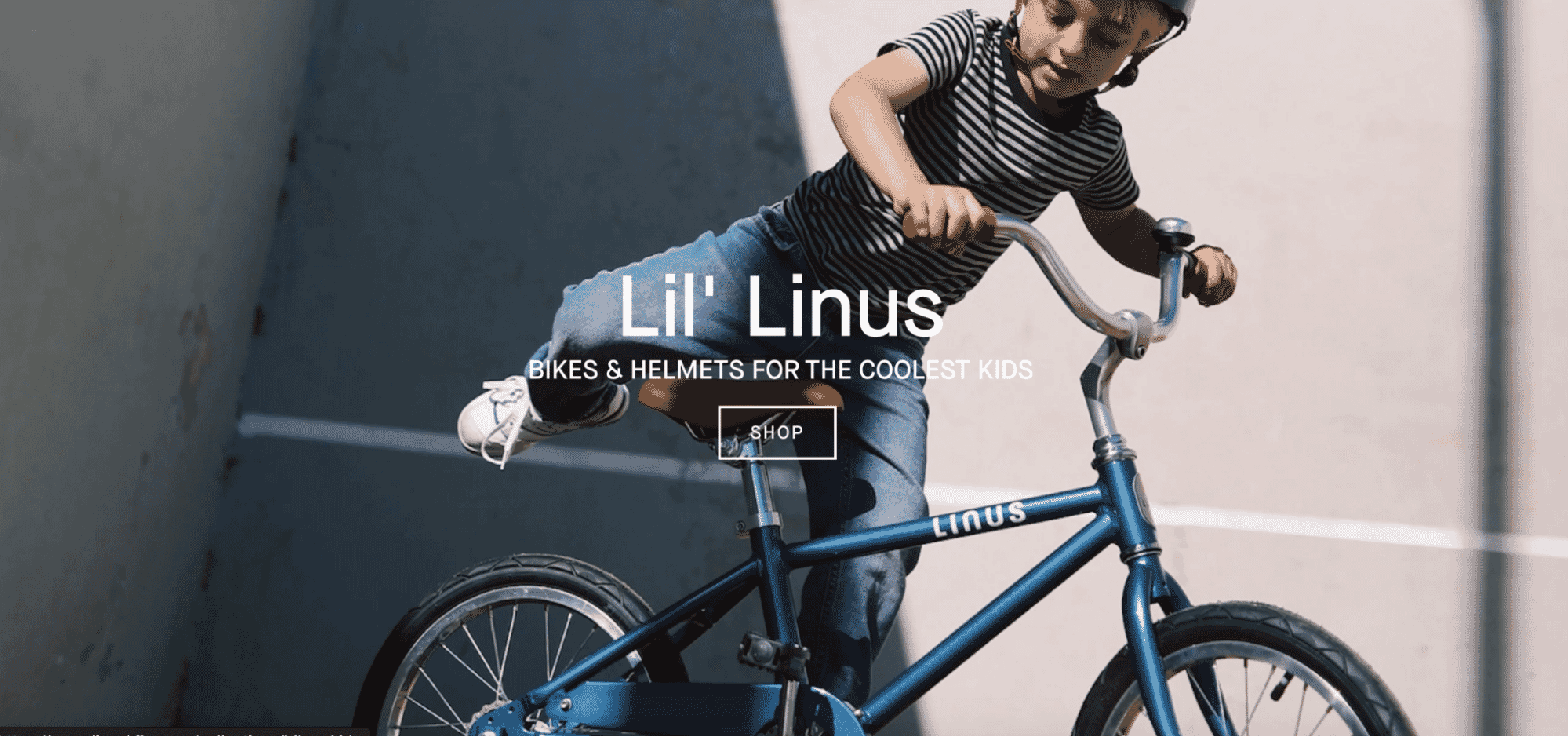

27. Linus

Image source

This example from bike brand Linus takes a lifestyle over product approach. We’re sold on the vibe before the bike. It’s aspirational but also relatable—perfect for parents and cool kids alike.

The mid-movement shot adds energy and makes the product feel fun and adventurous. The text placement is smart: bold, centered, and readable without overpowering the image.

28. Pow Gloves

Image source

Pow Gloves delivers high-impact product photography that leans into performance, texture, and environment. Shot in snowy alpine conditions, its imagery captures real-world functionality while keeping the product in crisp focus.

Frosted lenses, fleecy knits, and matte leathers pop against blurred white backdrops, highlighting both material quality and cold-weather capability. The models are active but cropped, letting the gloves and headwear shine without distraction.

29. Beestinger

Image source

Beestinger’s product photography balances precision and action, capturing the high-performance world of archery stabilizers. Each image speaks directly to its audience—whether it’s competitive target shooters or camo-clad hunters—by showing the gear in realistic, high-stakes contexts.

Sharp detail on textures like carbon fiber, metal finishes, and compound bows communicates quality and durability. Meanwhile, the use of tight crops and dynamic angles keeps the focus on function, not fluff. By pairing lifestyle imagery with close-up product visuals, Beestinger hits the bullseye on authenticity and trust—two essentials in any performance-driven category.

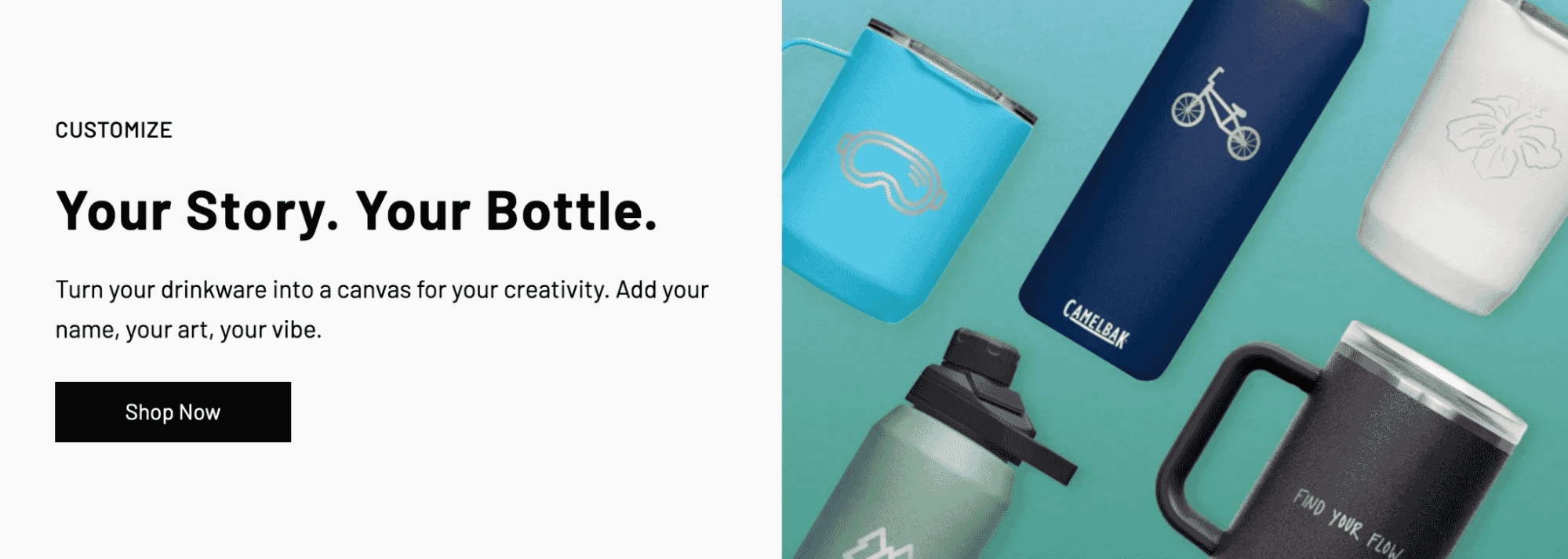

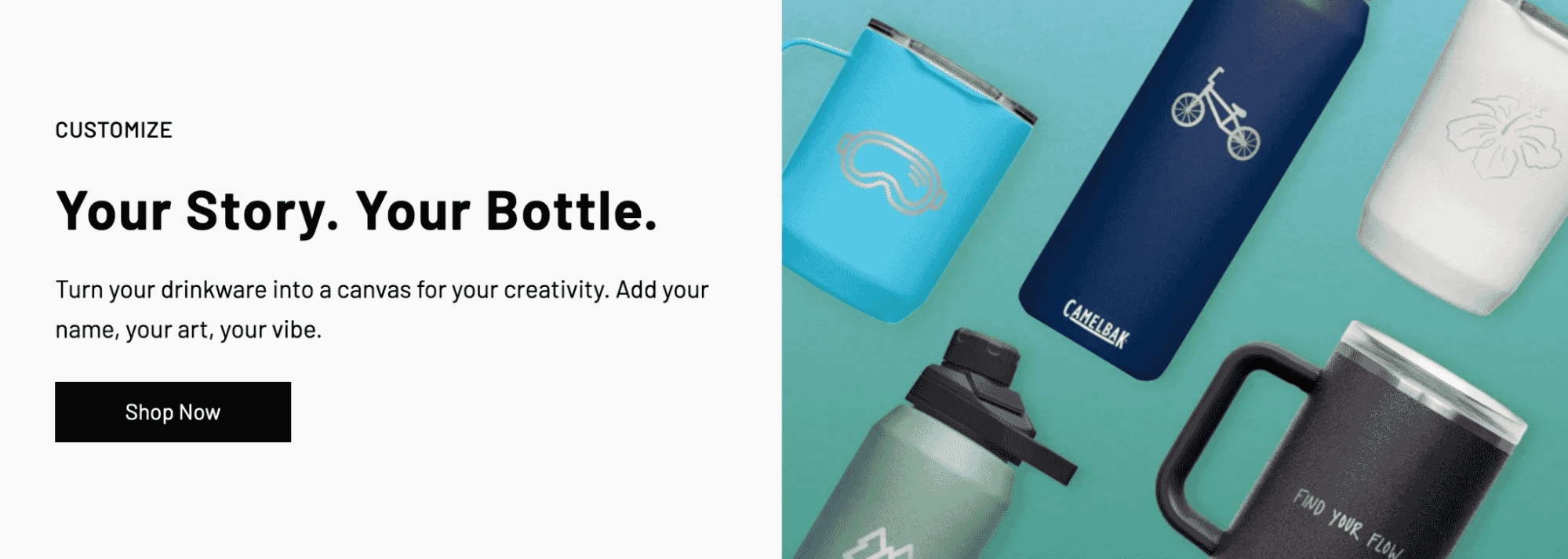

30. CamelBak

Image source

The top-down flat lay showcases CamelBak’s water bottles in a scattered, playful arrangement. Each bottle is angled differently, giving the scene energy and allowing each product to stand out while still feeling part of a cohesive set.

The smooth teal gradient adds visual interest without stealing the spotlight. It complements the product colors and adds depth, helping the matte finishes of the bottles pop.

The lighting is soft but directional enough to highlight the textures—especially the powder-coated surfaces and engraved designs. This gives a tactile sense of quality without relying on close-ups.

The photo manages to feel unified while showing a range of products: mugs, tumblers, bottles—each in a different color and size. It’s a great way to communicate customization options without crowding the frame.

31. Lift Foils

Image source

Lift Foils captures the thrill and elegance of hydrofoil surfing through cinematic, lifestyle-driven photography. Their imagery effortlessly blends action and atmosphere—highlighting both product performance and the aspirational lifestyle that surrounds it.

From crisp shots of foil boards slicing through tropical waves to grounded moments of riders gearing up at the shoreline, every frame conveys motion, freedom, and connection to nature. The gear is presented in real use, allowing water, sunlight, and setting to act as natural visual enhancers. This approach not only showcases the quality of the product but also sells the lifestyle it unlocks. It’s adventure marketing at its finest.

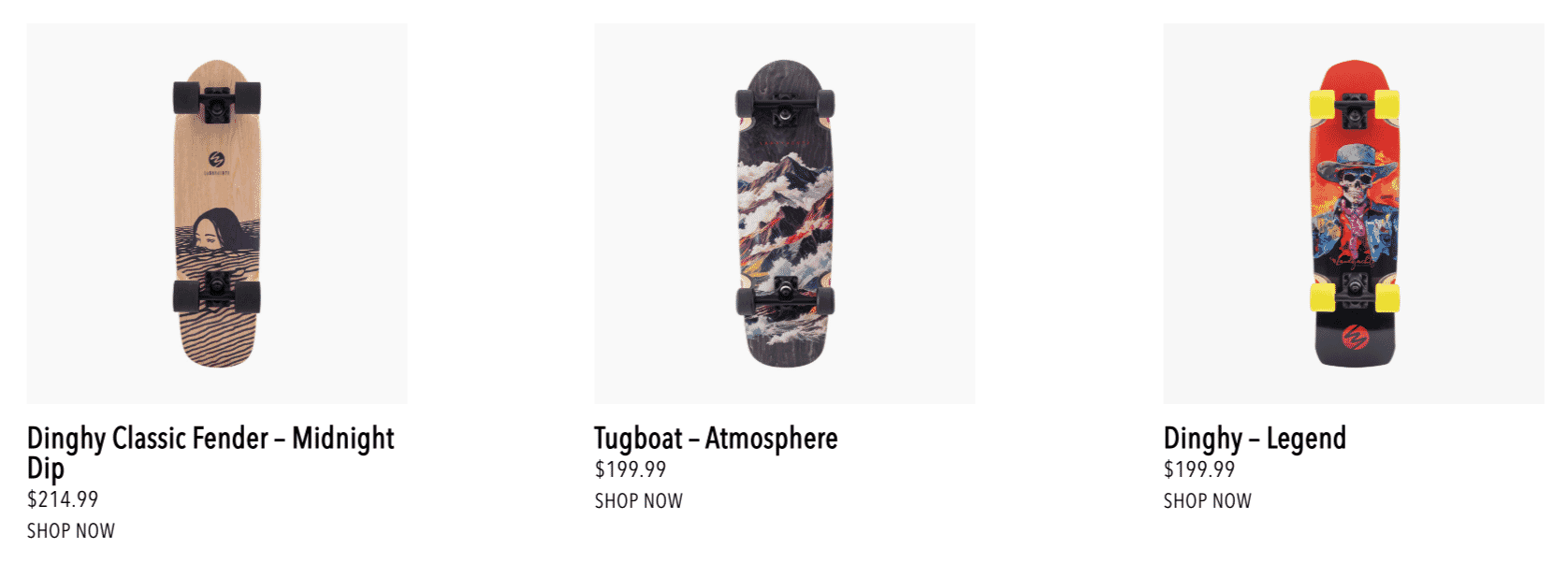

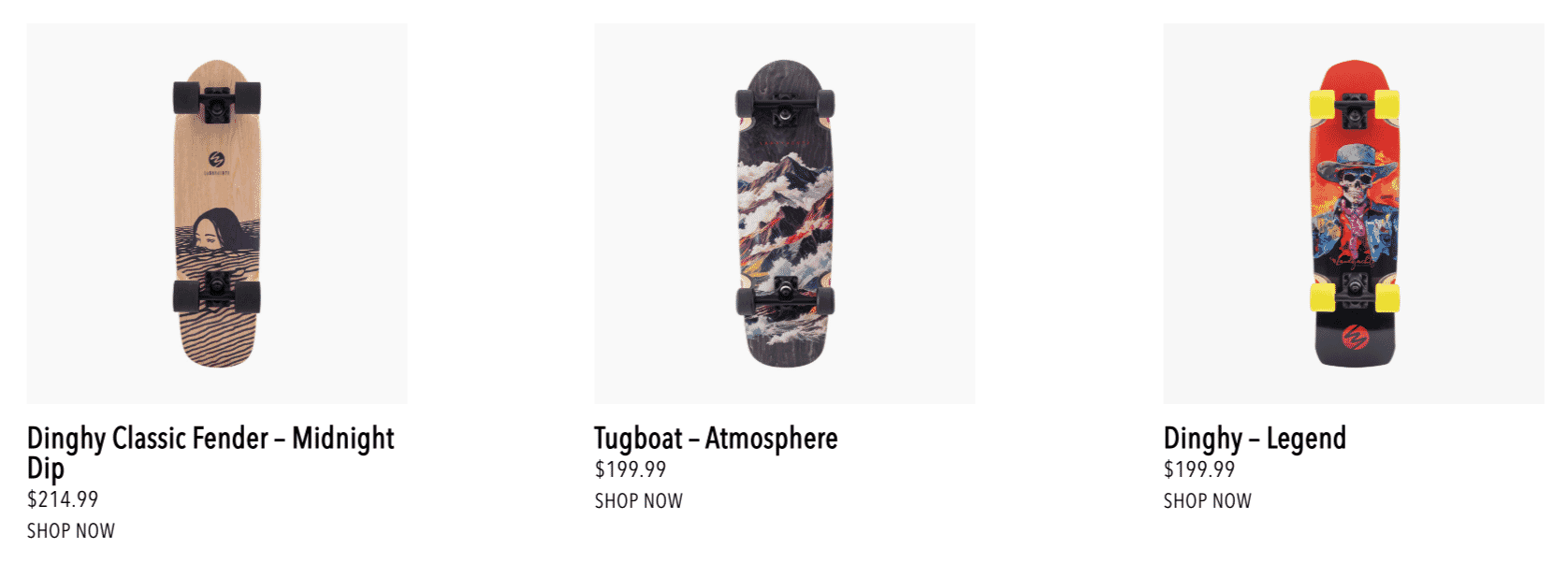

32. Landyachtz

Image source

Landyachtz uses clean, minimal product photography to make bold skateboard designs pop. Set against bright white backgrounds, each board is perfectly centered and evenly lit, allowing the intricate deck artwork—from hand-illustrated mountains to surreal portraits—to shine without distraction.

This studio-style approach highlights every detail of shape, texture, and color, making the craftsmanship unmistakable. The consistency across the images also creates a seamless browsing experience, while the sharp, high-resolution shots invite zoom-level inspection. It’s a textbook example of how white-background photography can still feel expressive and brand-forward.

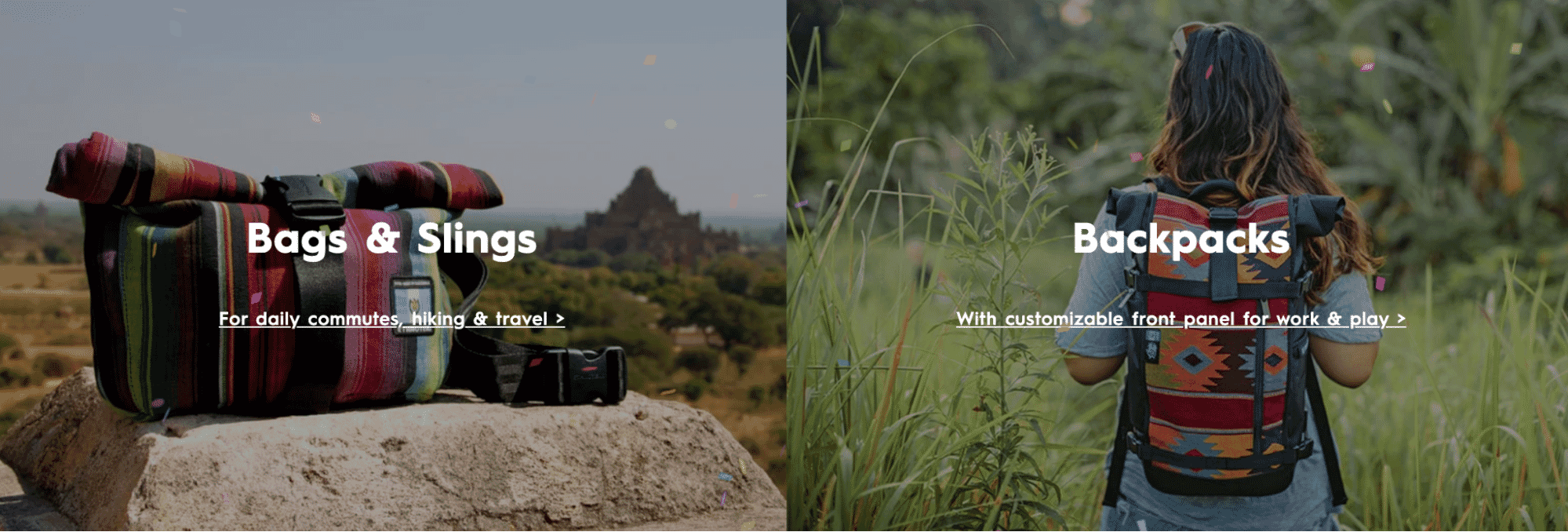

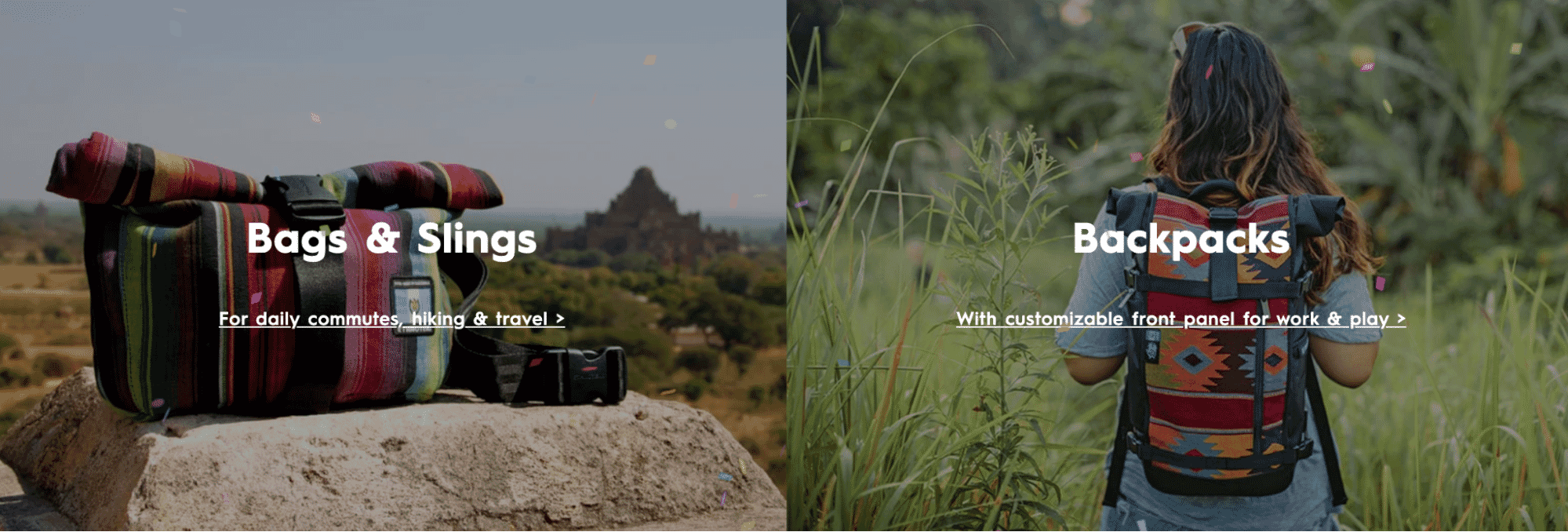

33. Ethnotek

Image source

Ethnotek’s product photography perfectly reflects the brand’s vibrant, adventure-ready identity. Shot in natural, wild settings, their bags are photographed in real-world use—slung over shoulders, perched on rocks, or trekking through fields.

This lifestyle-forward approach puts the product in context, emphasizing durability and design for travel and outdoor enthusiasts. The saturated colors of the bags stand out beautifully against the natural backdrops, and each shot is carefully composed to showcase both form and function. The result is photography that feels aspirational, authentic, and deeply connected to the brand’s do-good, go-anywhere ethos.

Furniture and home goods

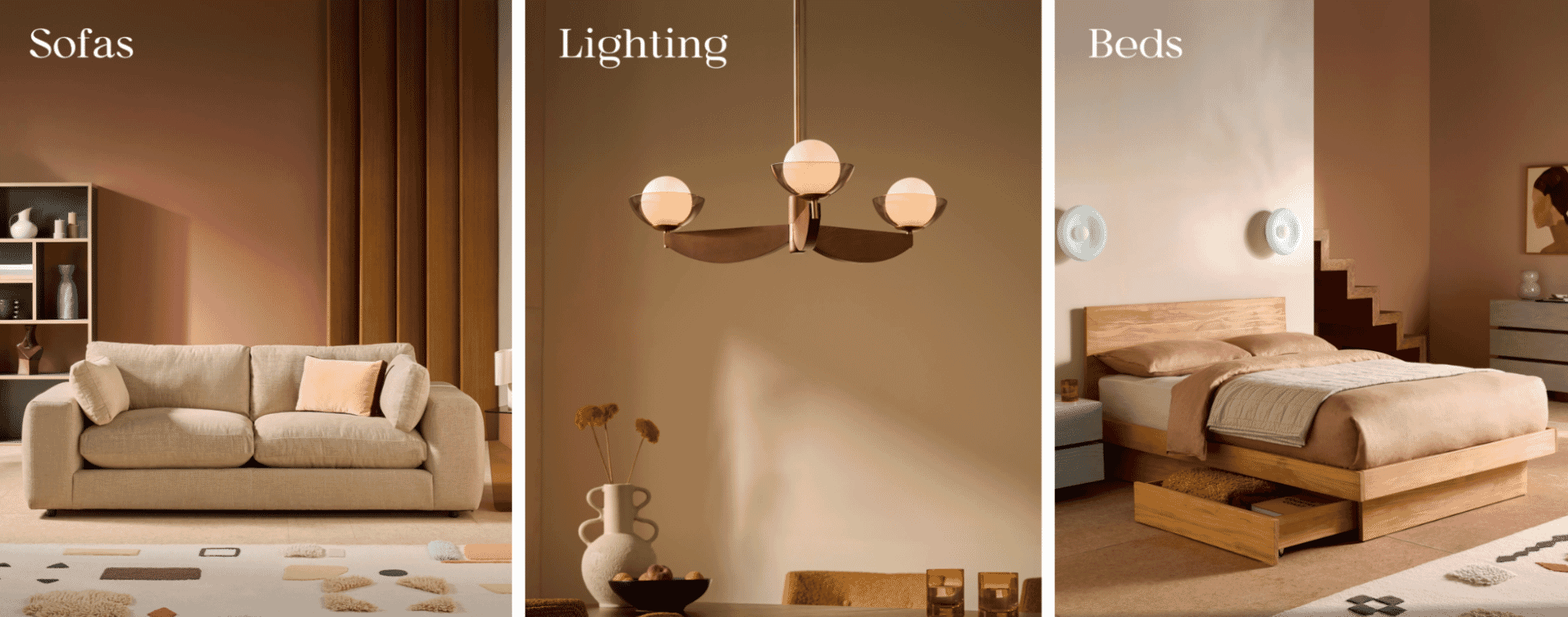

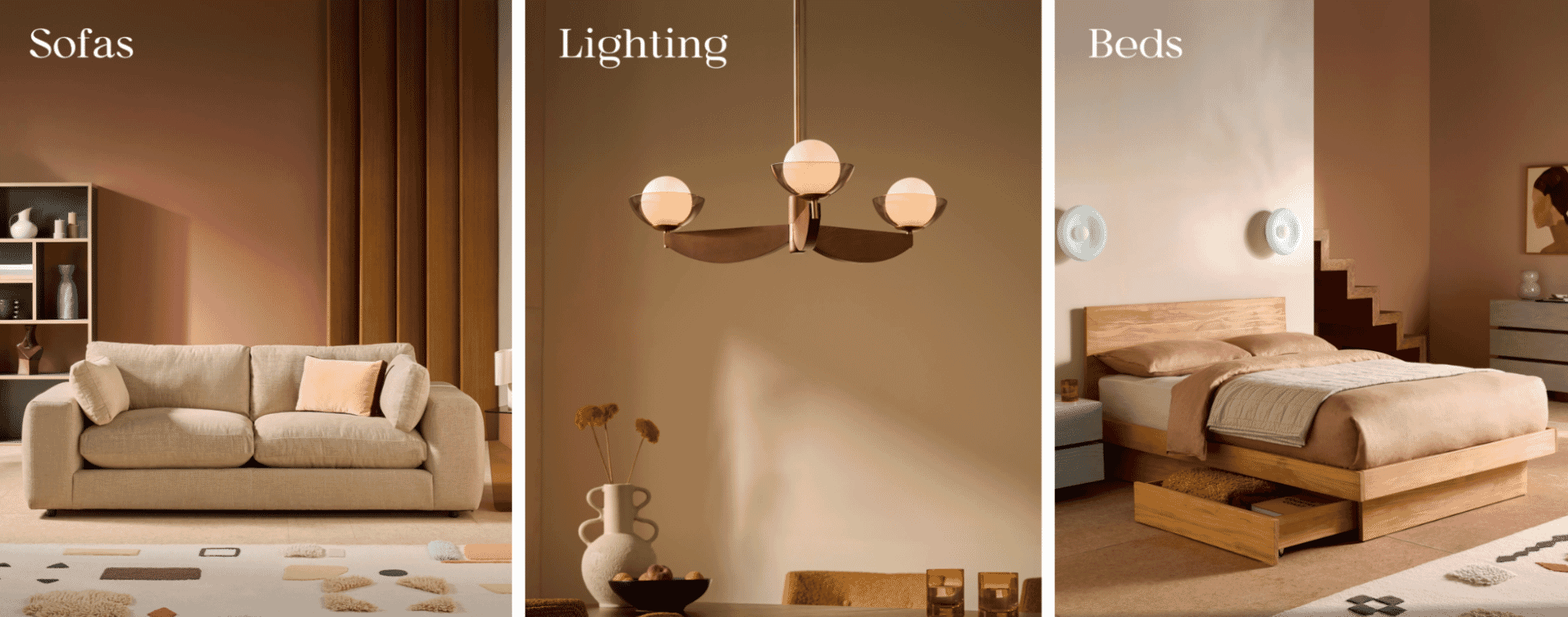

34. MADE

Image source

MADE’s product photography captures the harmony of modern living with a refined, editorial edge. Each image is carefully styled to showcase not just the product—sofas, lighting, or beds—but the ambiance they create. The lighting is soft and consistent, emphasizing texture, shape, and color in a natural way. Warm, muted tones pair with clean architectural lines, drawing the eye through the space and highlighting each design detail without distraction.

The result is an inviting, aspirational scene that feels livable yet elevated. MADE’s photography doubles as interior inspiration, turning every product into part of a cohesive lifestyle story.

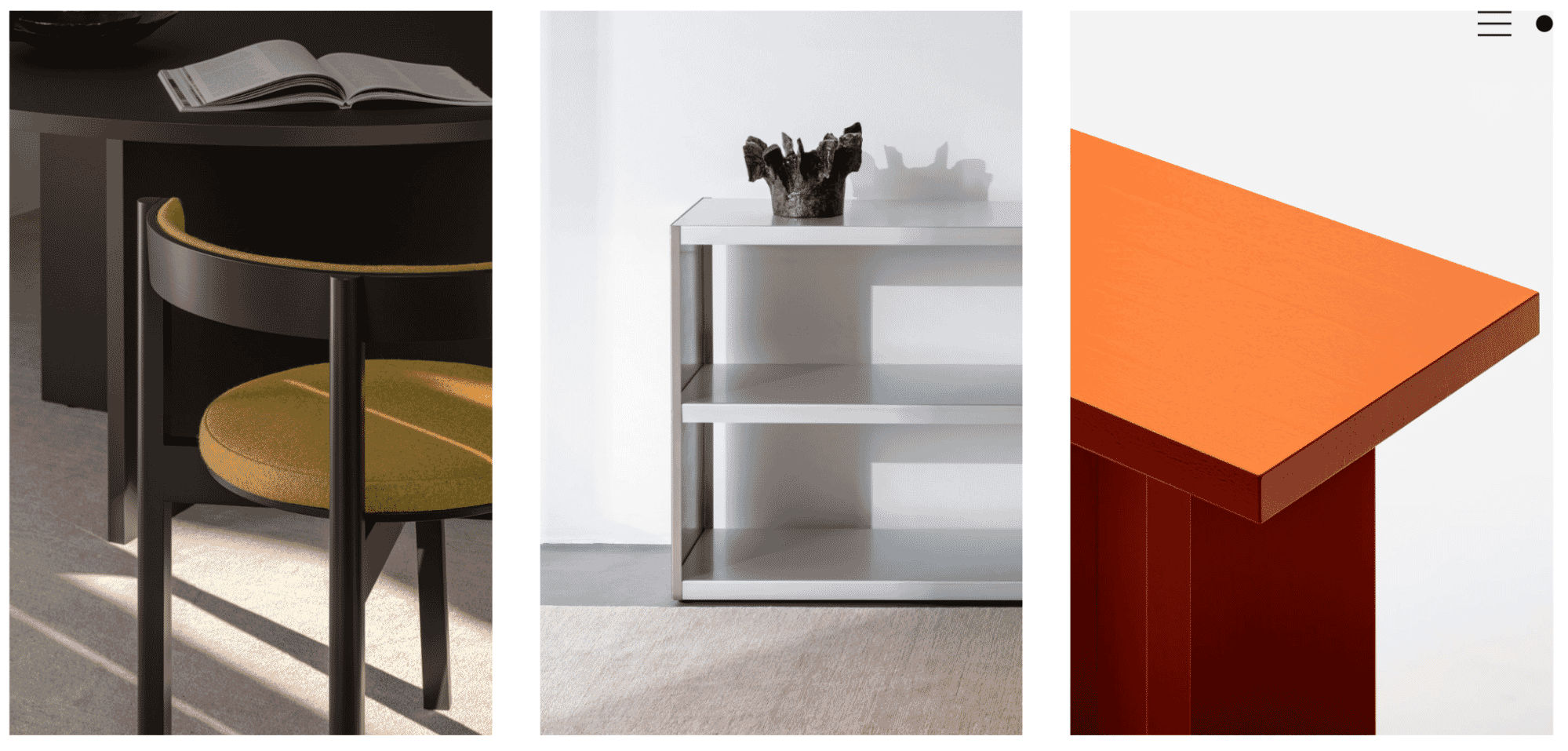

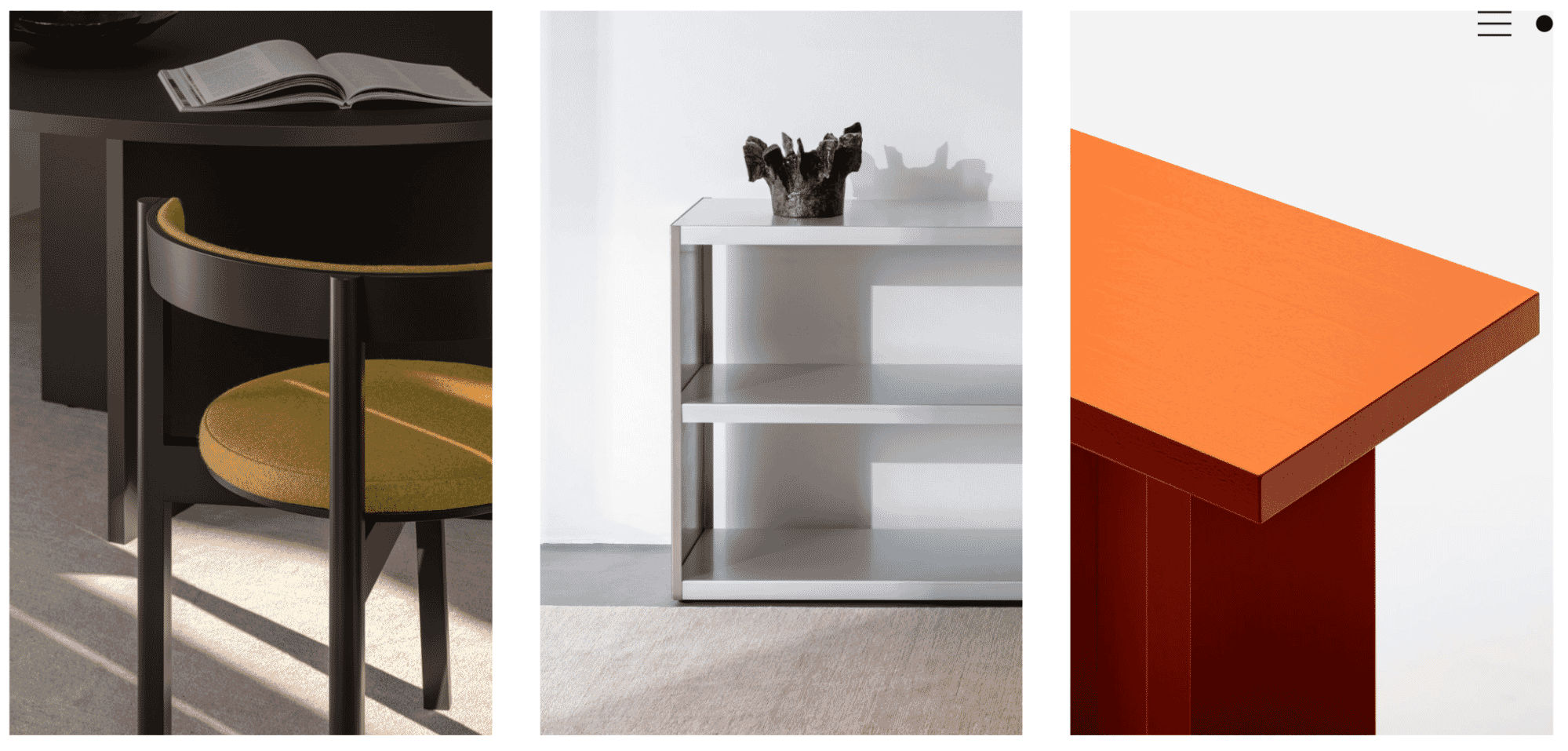

35. LOEHR

Image source

LOEHR’s product photography is a prime example of modern minimalism. With sharp, architectural compositions and pristine lighting, each image distills furniture design down to its purest form.

Materials and textures are foregrounded—brushed metals, matte lacquers, and soft upholstery—without unnecessary staging or visual clutter. The crisp shadows and natural gradients from ambient light add depth while preserving the clarity of shape and line.

The result is bold, geometric forms. LOEHR’s photography doesn’t just display a product—it reflects the brand’s design philosophy: functional, thoughtful, and quietly radical.

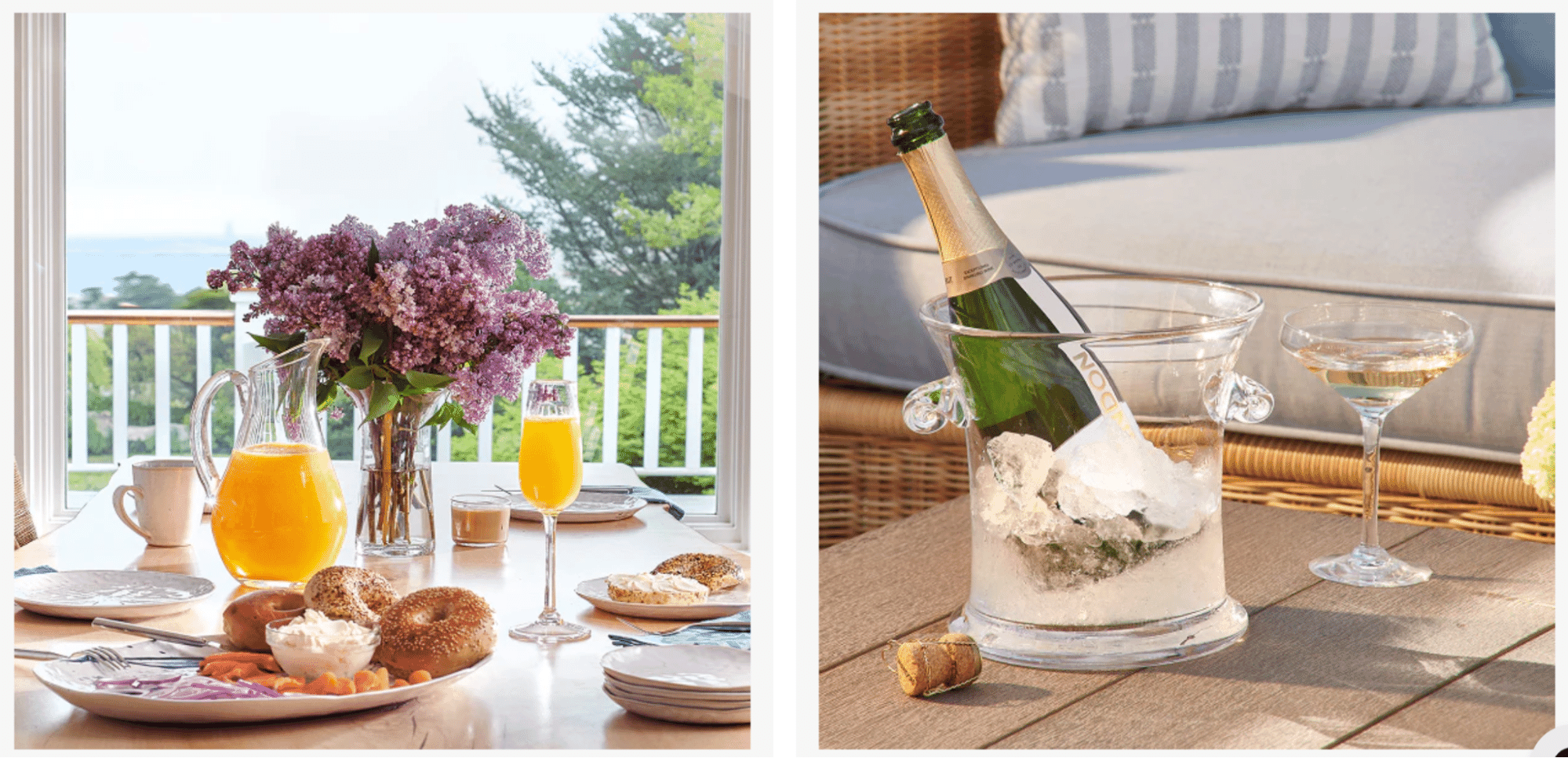

36. Simon Pearce

Image source

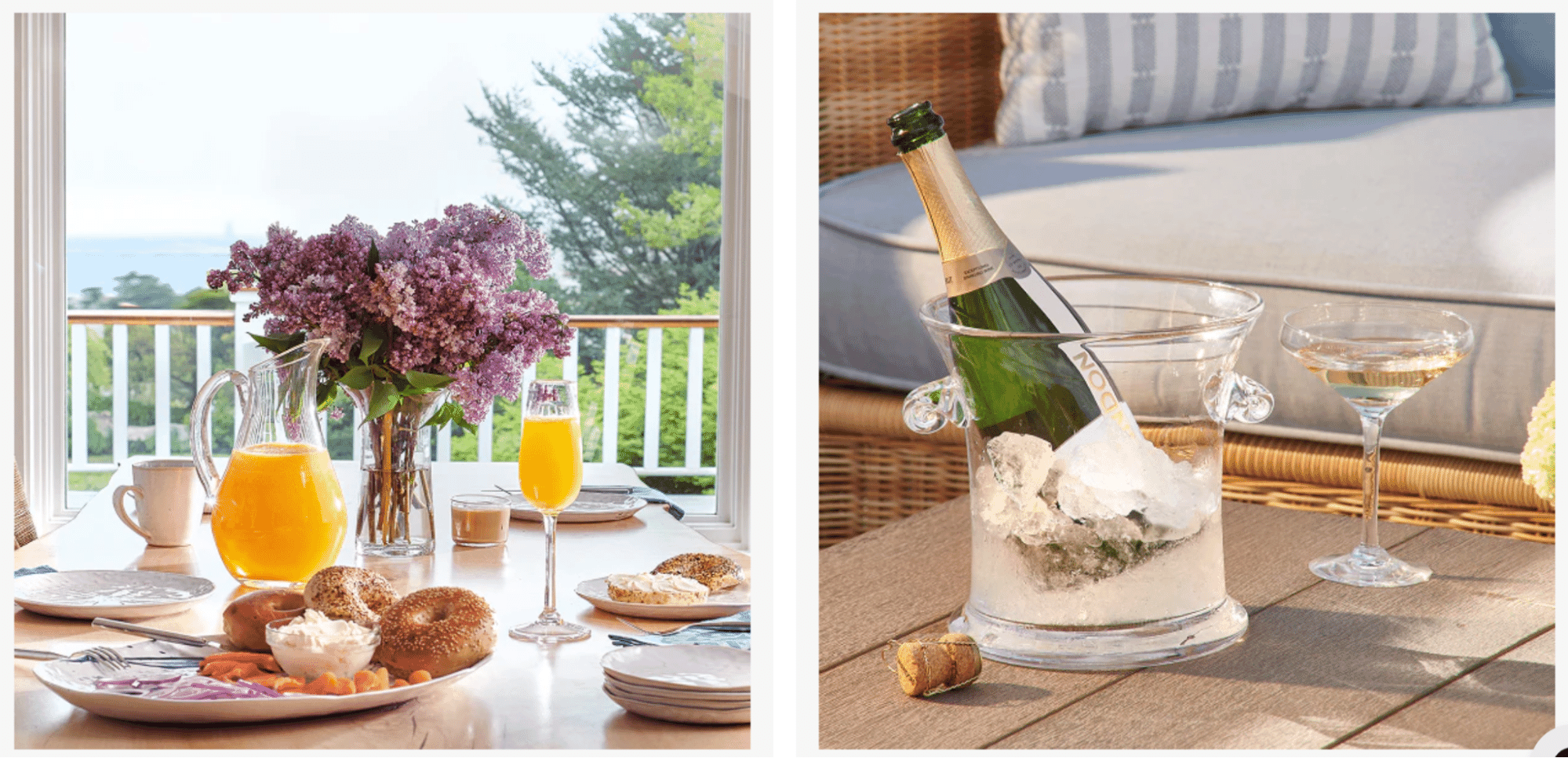

Set against airy, sun-drenched environments, Simon Pearce’s imagery brings out the artisanal quality of each glass and ceramic piece. The clear sparkle of handblown glassware, the creamy textures of stoneware, and the golden tones of sunlight on surfaces are all captured with refined precision. Lifestyle compositions feel warm and inviting—perfectly styled without feeling staged.

Whether it’s a mimosa brunch or champagne on the patio, the photography captures the brand’s essence: craftsmanship, comfort, and understated luxury. This is storytelling through light, texture, and good taste.

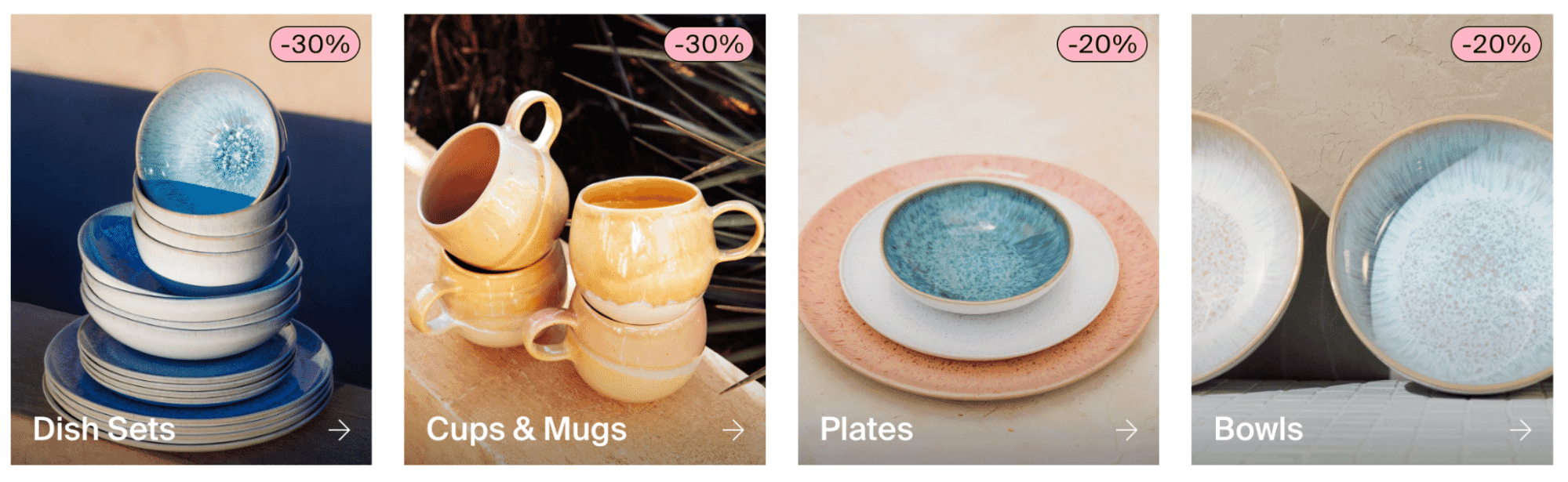

37. Motel a Miio

Image source

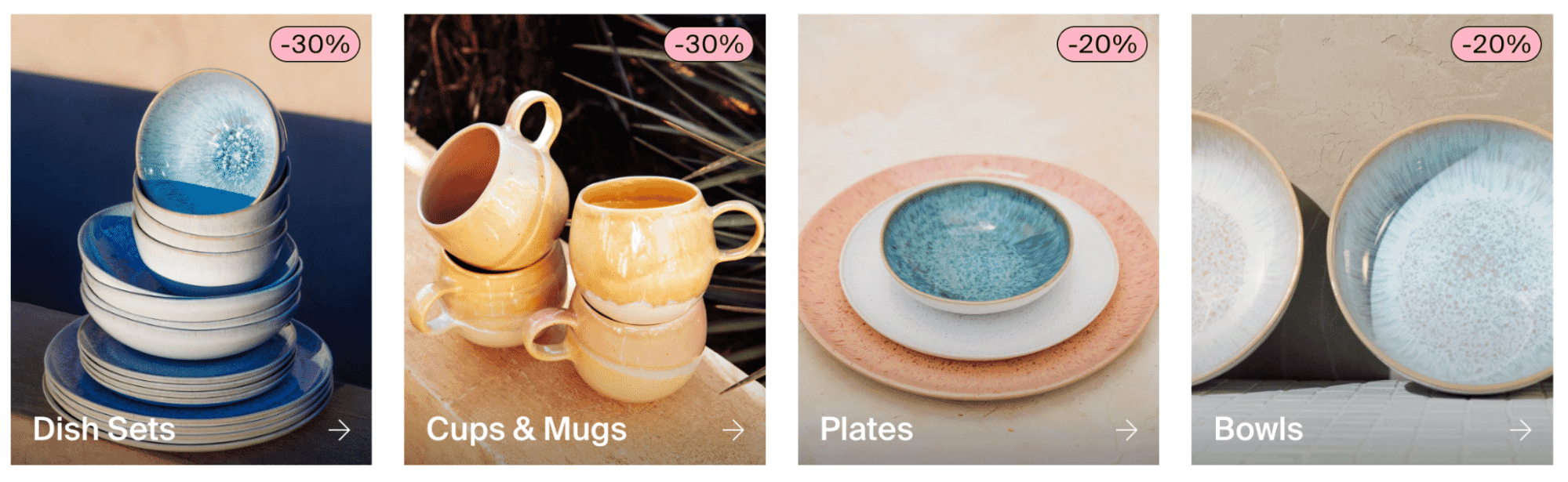

Motel a Miio’s product photography bursts with color, warmth, and Mediterranean charm. The brand highlights the artisanal quality of its handmade ceramics through rich textures, sunlit surfaces, and thoughtful arrangements.

Each image showcases the uniqueness of glazing and form—from the dreamy aqua blues of bowls to the peachy-pink blush of plates. Natural shadows and earthy backdrops give the shots a tactile, sun-kissed feel, inviting viewers to imagine relaxed outdoor dining or cozy kitchen moments. The photography is not just beautiful—it’s transportive, evoking a laid-back, design-forward lifestyle rooted in craftsmanship.

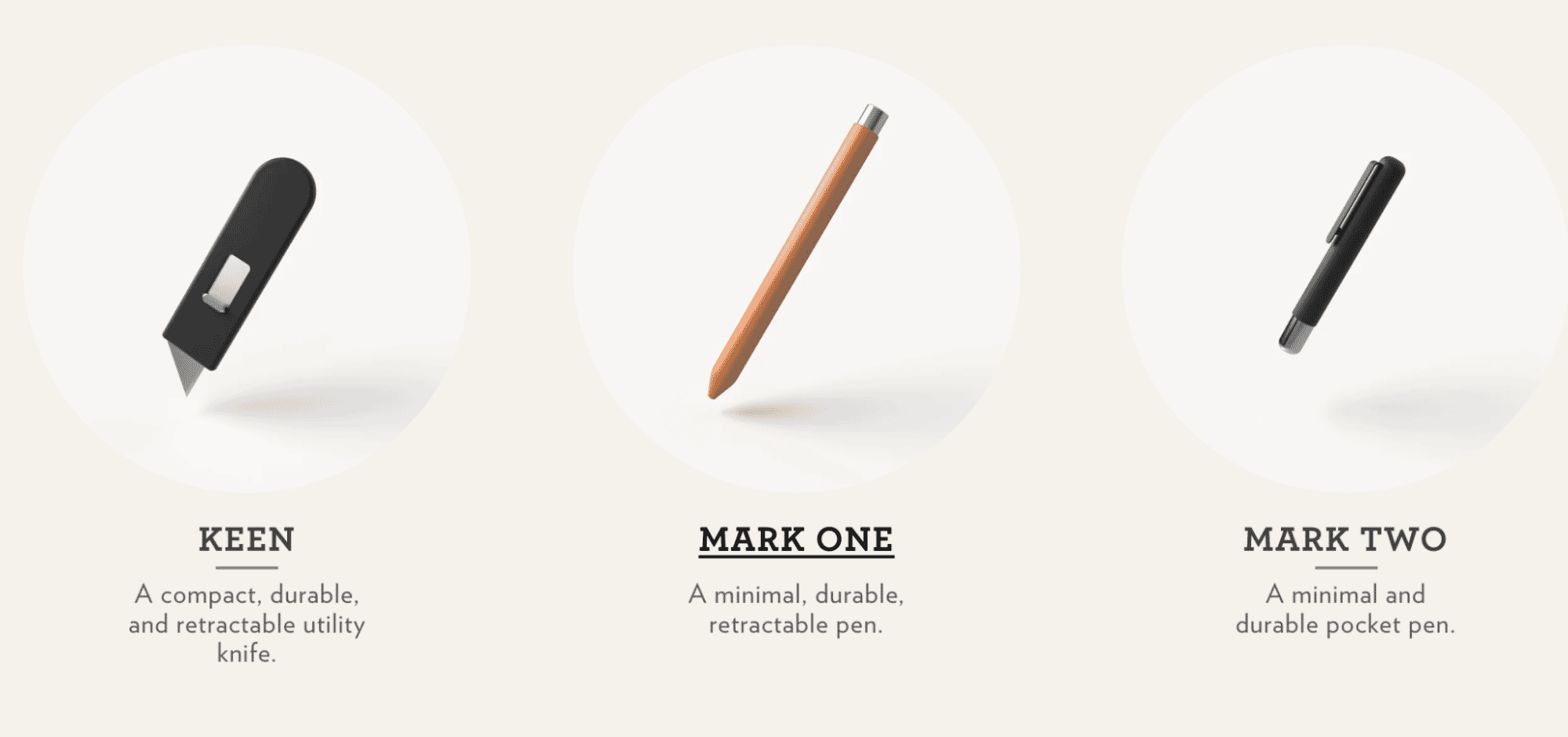

38. Studio Neat

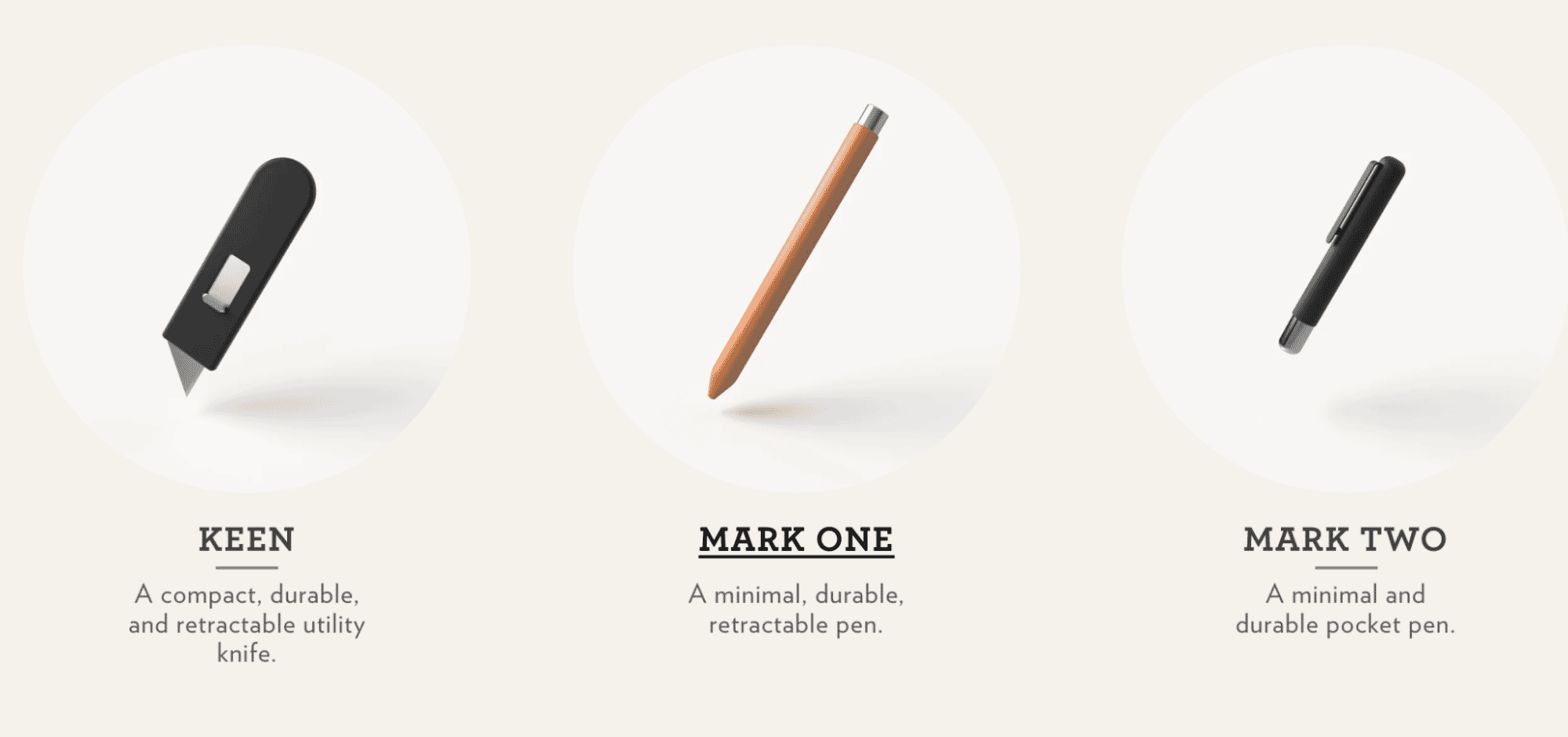

Image source

Studio Neat uses minimalist product photography. In this example, each item is suspended against a clean, white backdrop with gentle shadows, emphasizing their streamlined form and material finish. The floating composition gives the products a modern, weightless feel, aligning with their functional and design-forward ethos.

Every visual choice—neutral lighting, soft gradients, centered framing—supports a sleek and utilitarian aesthetic.

Cars and automotive

39. Carvana

Image source

Carvana takes a clean, uniform approach to product photography by displaying each vehicle category in profile against a pure white background. The consistency in angle, lighting, and car color (white) helps customers compare models quickly while reinforcing trust through visual clarity.

For ecommerce brands managing large SKUs or configurable product categories, this style benefits from clipping path, retouching, and shadow effects to ensure clean, scalable presentation across all digital platforms.

40. CarBahn

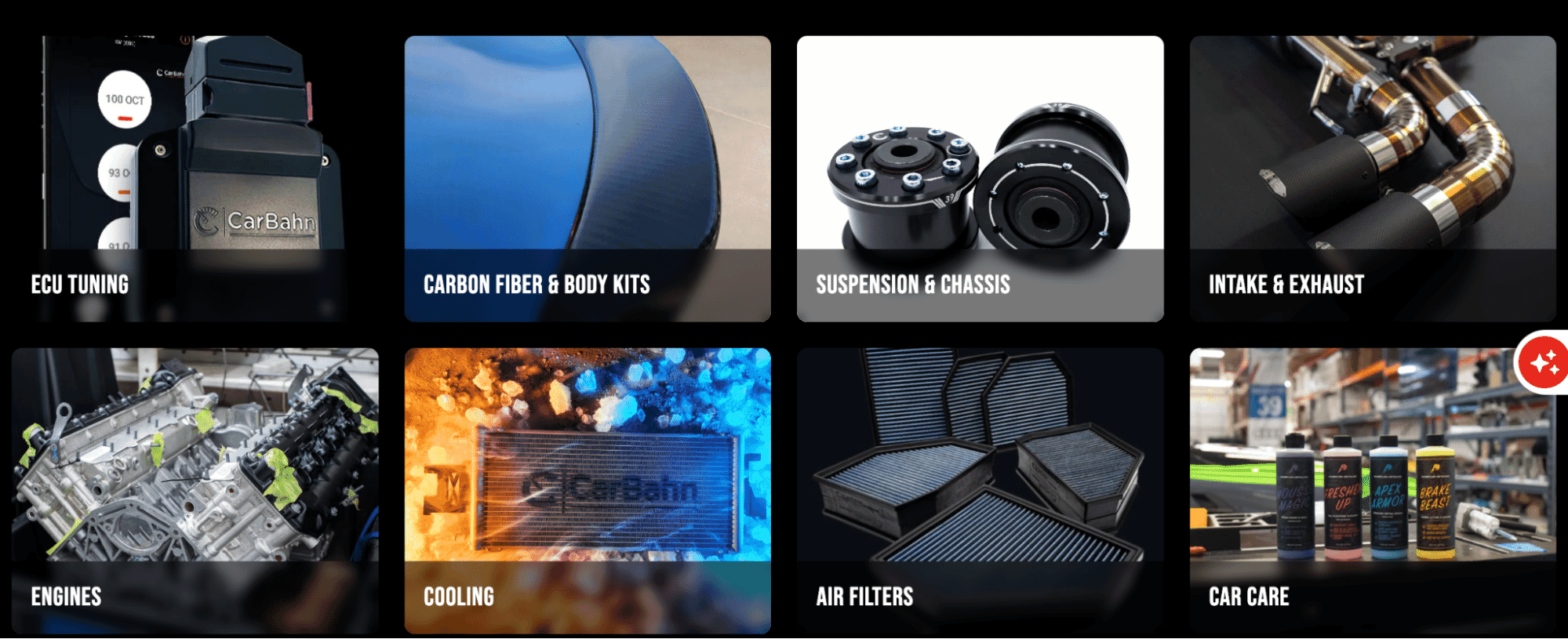

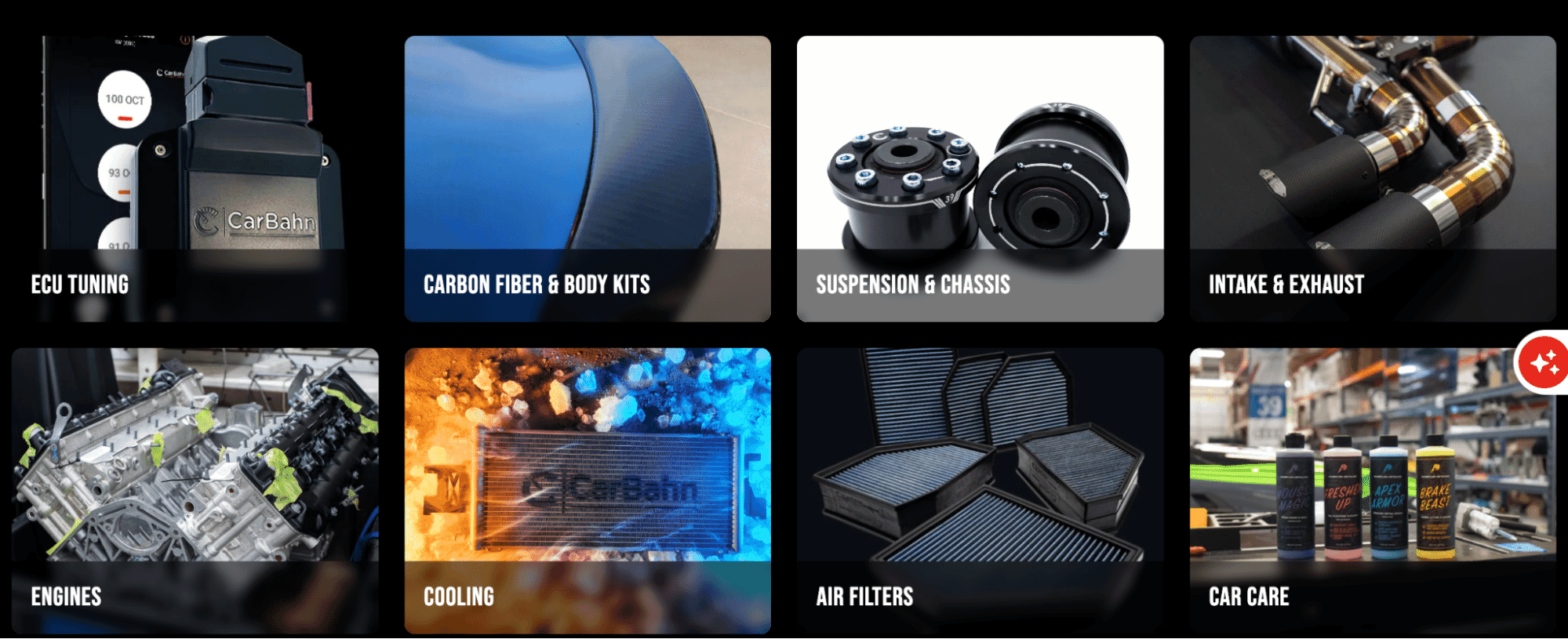

Image source

CarBahn’s product photography leans into a high-performance, gearhead aesthetic with bold contrast, sharp lighting, and industrial backdrops. Each category image emphasizes material texture and mechanical precision. There’s a tactile, real-world feel, with shots that oscillate between clean studio setups and gritty workshop environments.

This style is ideal for performance auto brands. Related edits might include color correction, reflection and glare removal, and precision shadow work to enhance contrast and depth without over-editing the hardware’s raw appeal.

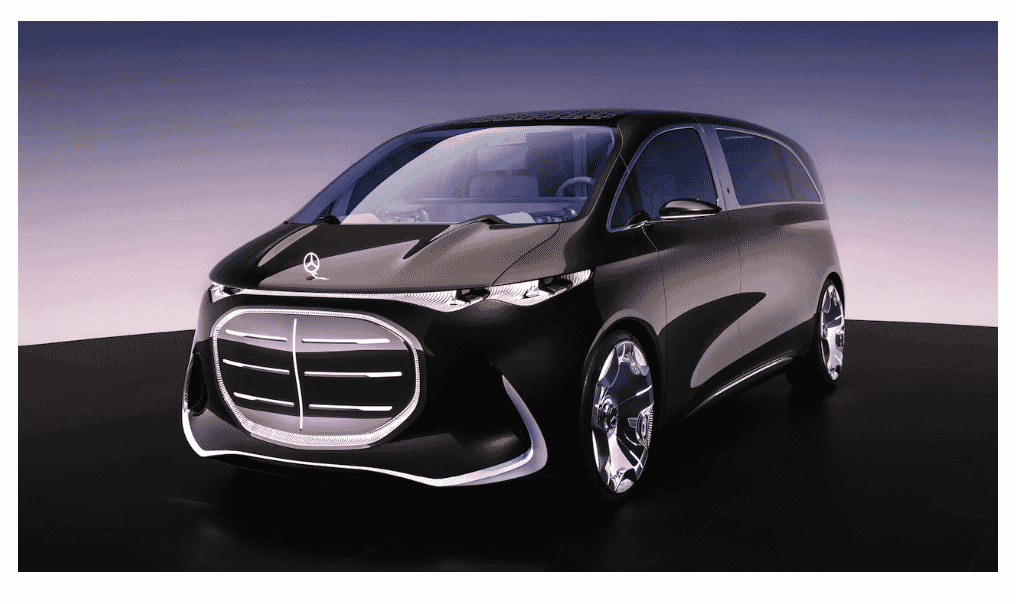

41. Mercedes-Benz

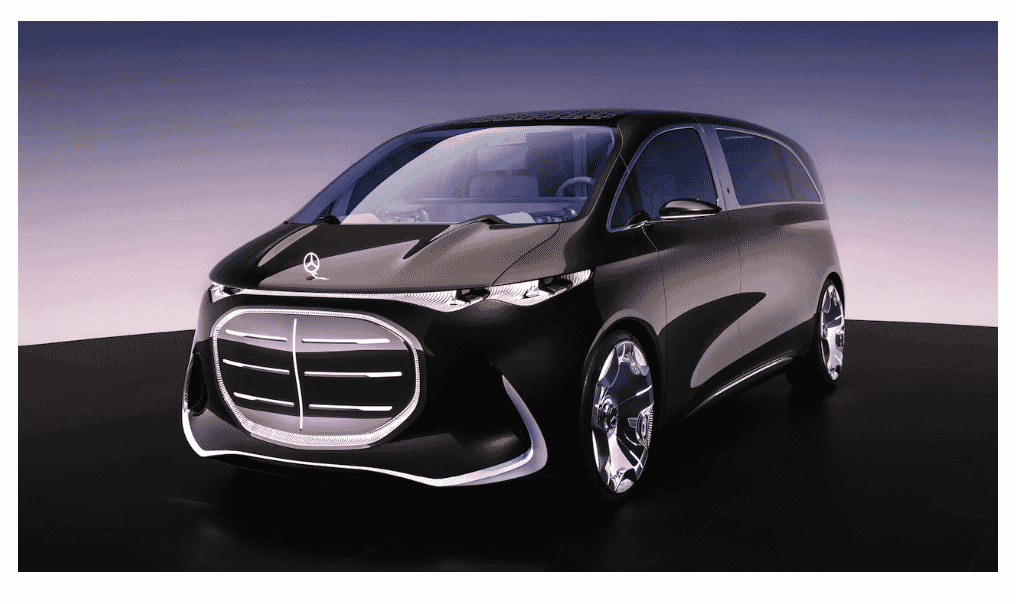

Image source

Mercedes-Benz’s product photography captures futuristic elegance with cinematic precision. This concept vehicle is shot under ambient, gradient lighting that complements the sleek contours and metallic finish, making it feel like a luxury object from the future. The low angle and subtle reflections emphasize design innovation—fluid lines, illuminated details, and aerodynamic form—while keeping the focus on craftsmanship and vision.

Lifestyle and miscellaneous

42. StickerBrand

Image source

StickerBrand’s product photography transforms wall decals into immersive, real-life design statements. Each wall is staged in context—whether it’s a moody café corner or a leafy bedroom escape—so shoppers can picture the product in their own space. The lighting is soft and natural, allowing the decals to blend seamlessly with furniture, textiles, and finishes while still standing out with crisp lines and vibrant color.

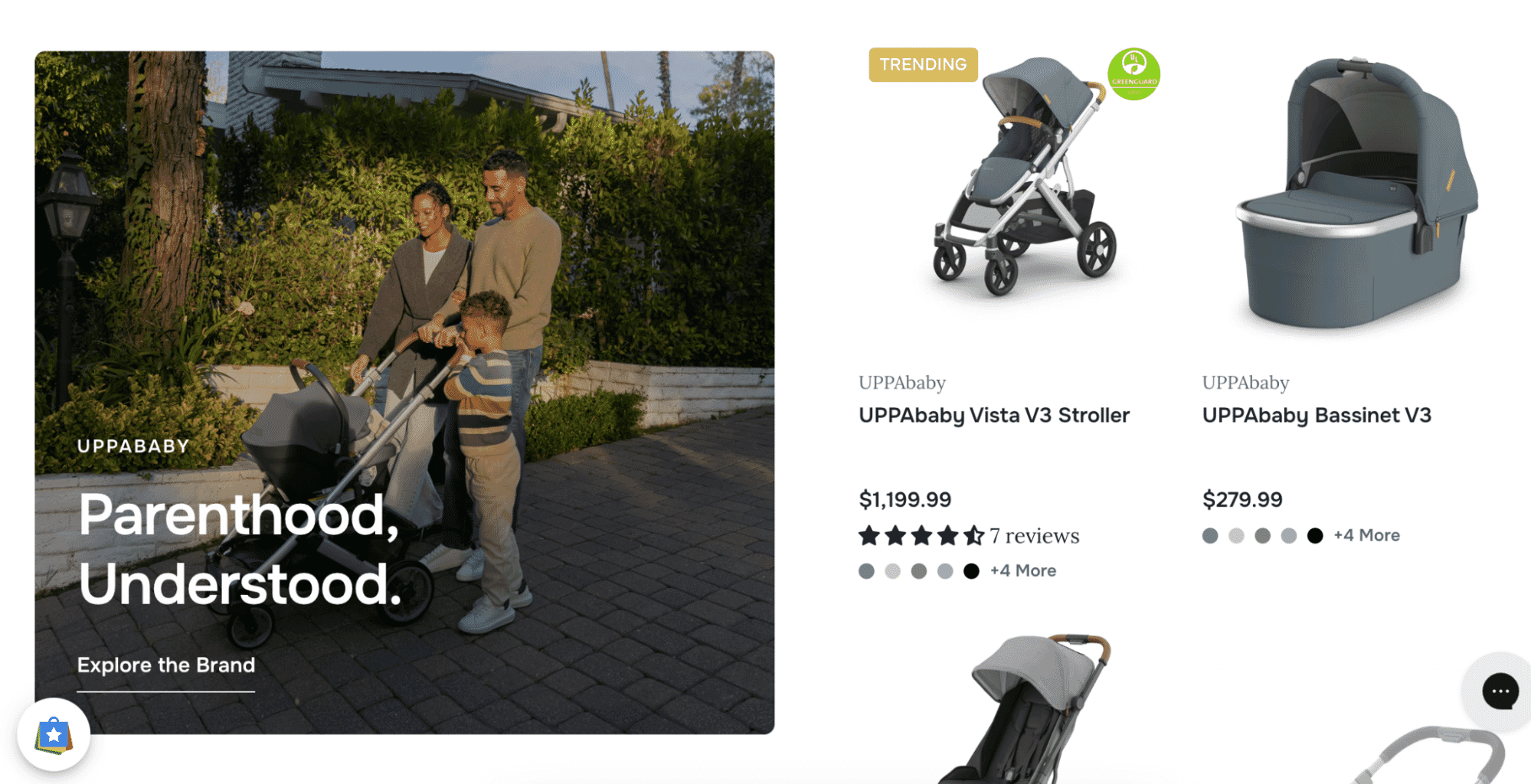

43. Bambi Baby

Image source

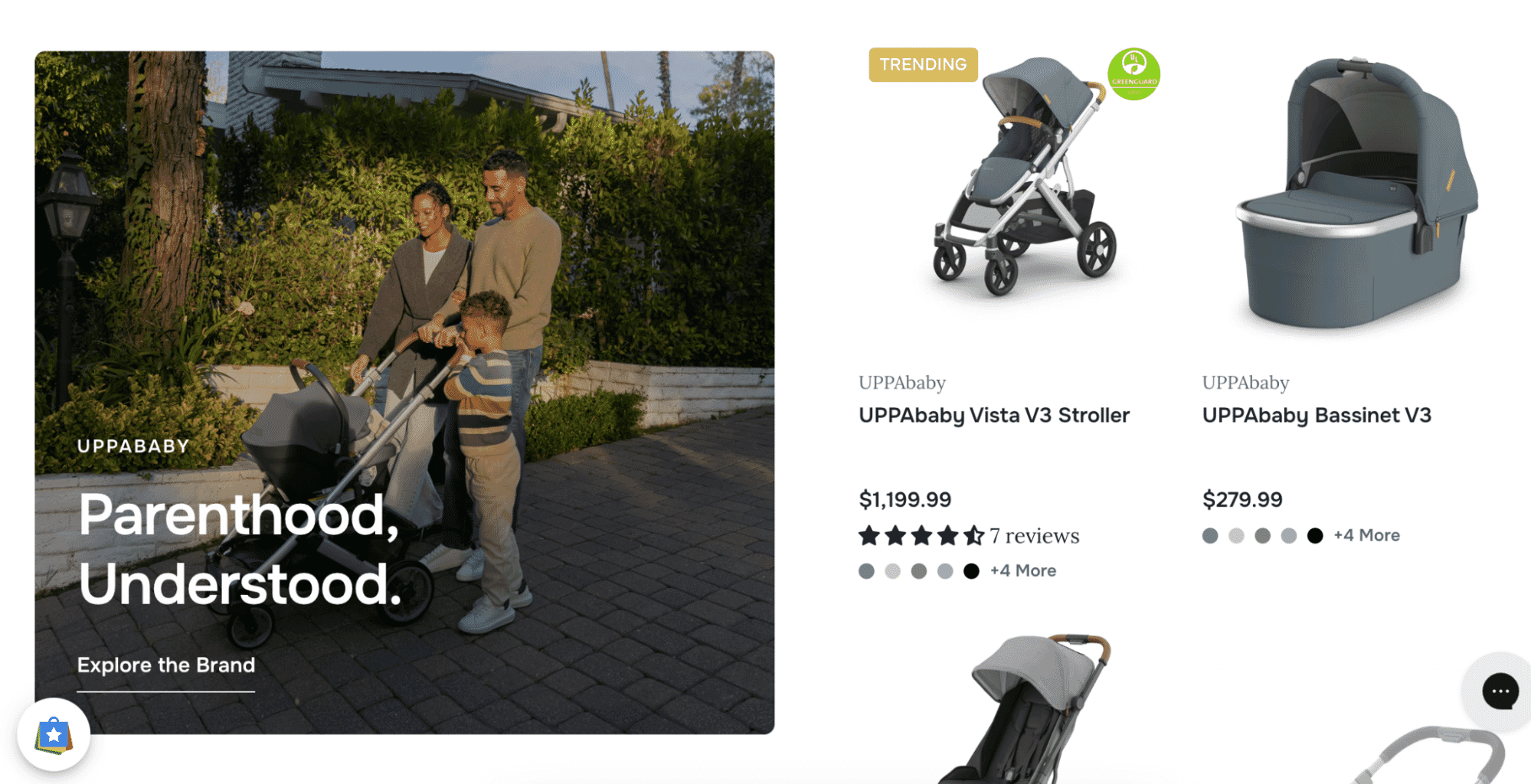

Bambi Baby’s product photography blends lifestyle and catalog styles to showcase both the function and feeling behind its premium baby gear.

The left side of this example shows a warm, everyday moment—a family on a walk at golden hour. This emotional lifestyle shot balances beautifully with the crisp, isolated product shots on the right, which highlight detail, color variations, and pricing. This dual approach supports both storytelling and conversion.

44. Bentley

Image source

Bentley’s luggage line embraces bold, clean, and ultra-modern product photography that celebrates color as a core brand identity. The suitcases are displayed in a tight lineup with seamless lighting and minimal shadows, highlighting each hue without distraction. The gradient floor and backdrop also complement the tones of each suitcase.

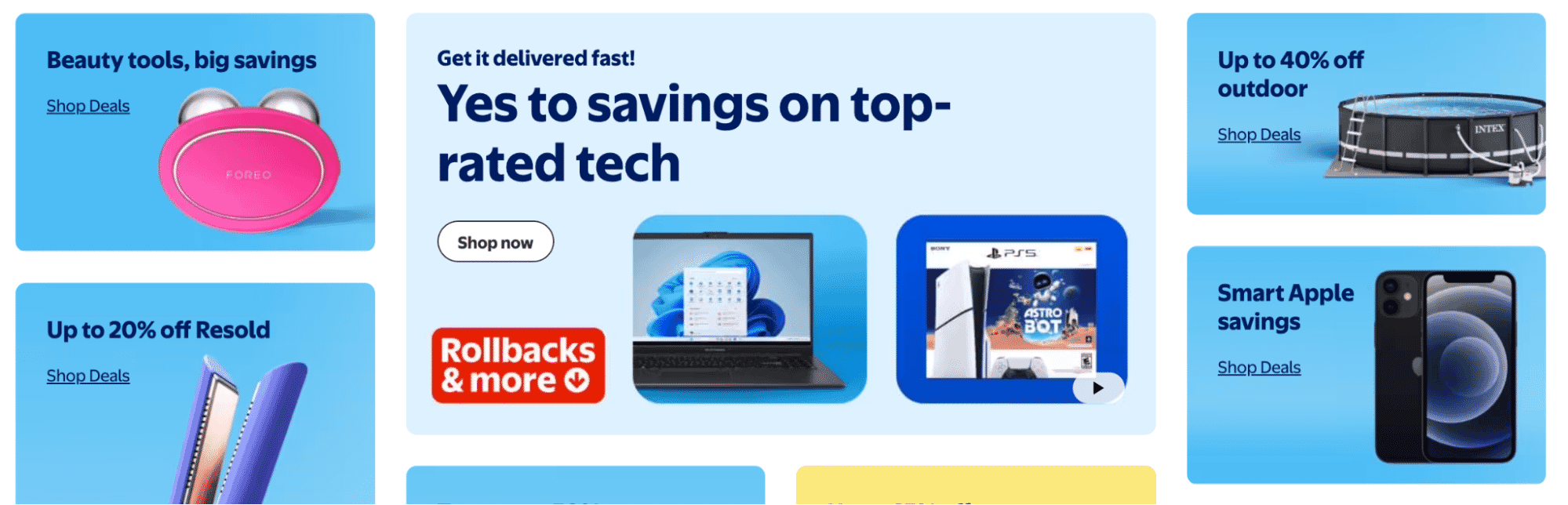

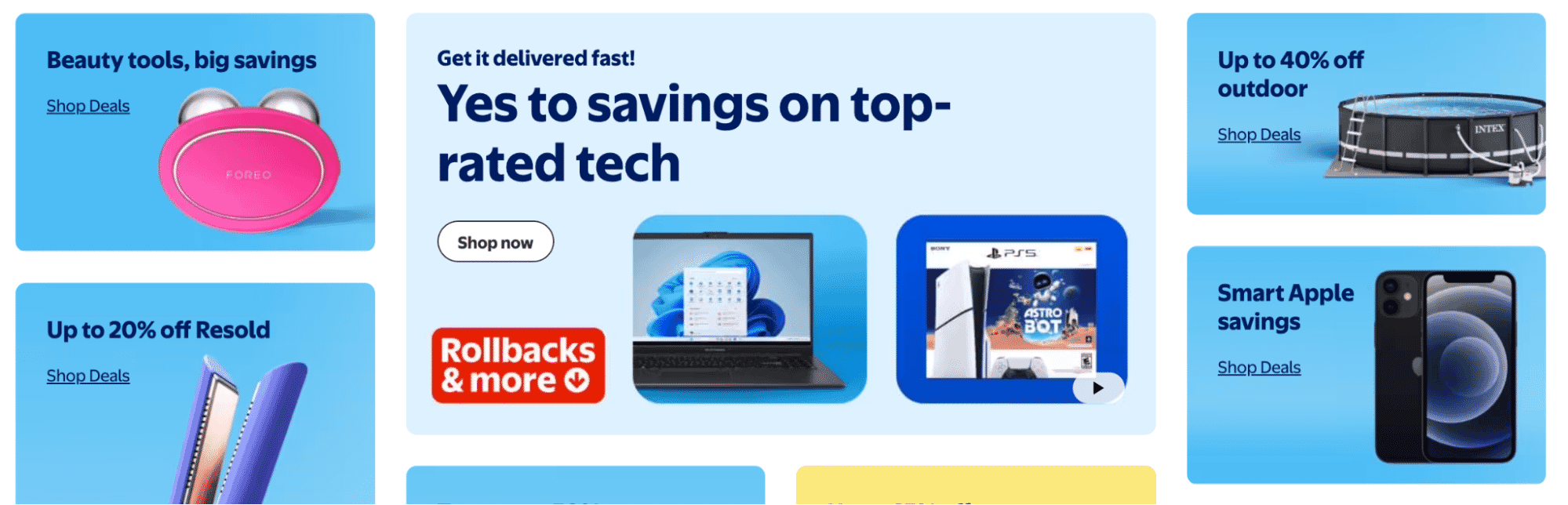

45. Walmart

Image source

Walmart uses bright, consistent, and brand-forward product photography to energize its promotional graphics. Each product—from beauty tools and smart tech to outdoor gear—is presented against soft, uniform color backdrops that create an airy and cheerful visual experience. Items are expertly isolated, often enhanced with clipping paths, drop shadows, and vibrant retouching to make them pop while maintaining a cohesive brand aesthetic.

Food and drink

46. Candy Club

Image source

Vibrant gummies, chocolates, and sour belts spill playfully from jars across a crisp white background, letting the intense colors and textures take center stage. The overhead layout creates a sense of abundance, while the neatly styled candy piles maintain a polished, crave-worthy aesthetic. Candy Club’s photos are a visual sugar rush that makes every sweet treat look like a party.

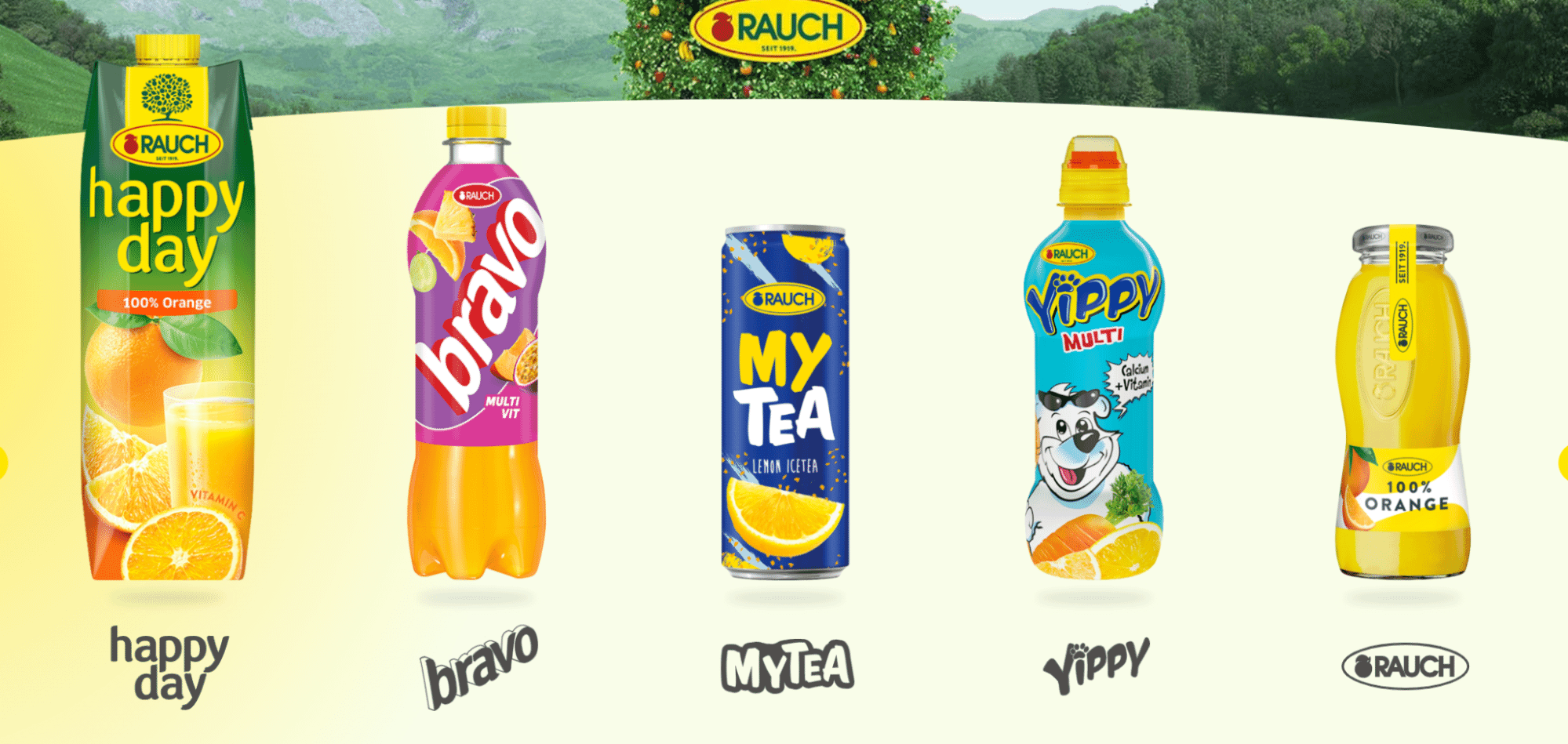

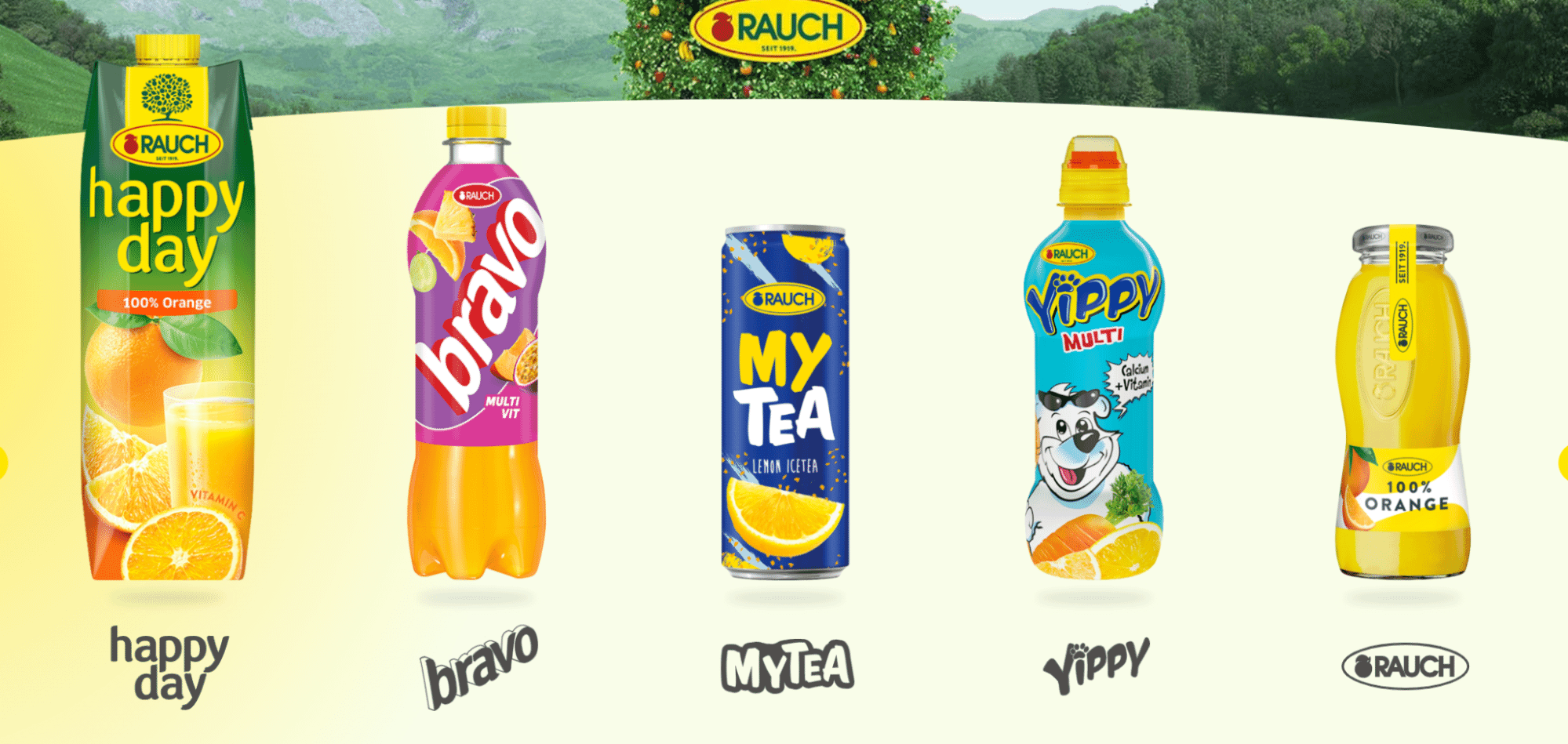

47. Rauch

Image source

Rauch brings a playful, shelf-ready polish to its product photography. Against a smooth gradient backdrop that shifts from citrus yellow to cream, each beverage line is given equal spotlight with symmetrical placement and minimal distractions.

Each product floats with a subtle shadow, allowing vibrant packaging to take center stage. The lighting is soft yet evenly distributed, enhancing the saturated colors and fruity visual cues without harsh glare.

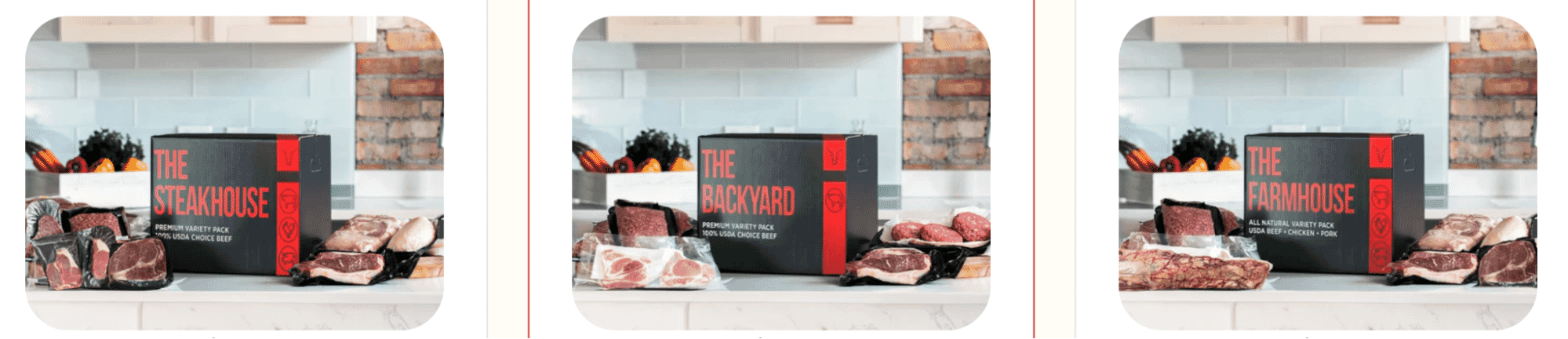

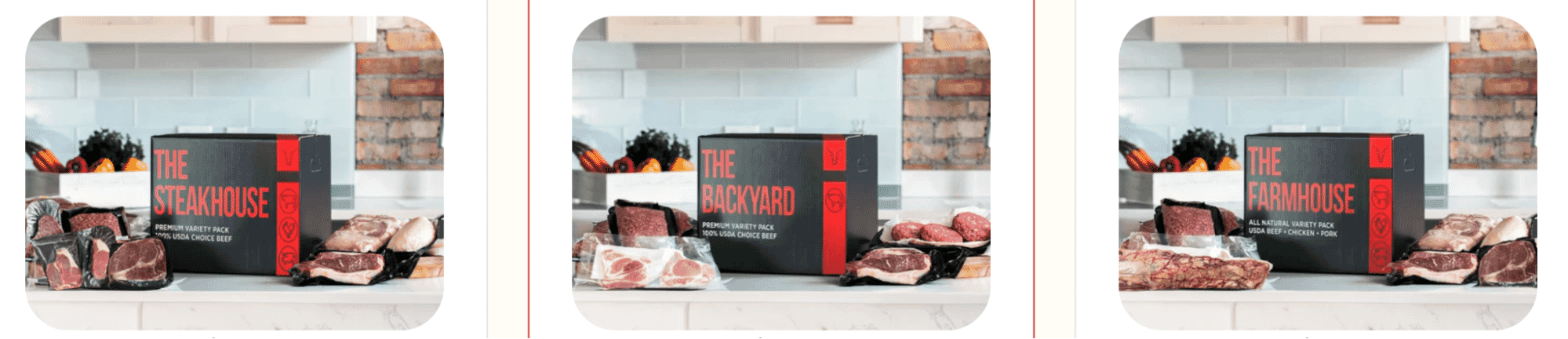

48. Backyard Butchers

Image source

Backyard Butchers nails a clean, trust-building presentation that’s perfect for high-value food subscriptions. Its product photography highlights premium meat packs in pristine kitchen settings with natural light, fresh produce, and minimal props—immediately reinforcing freshness, quality, and home delivery convenience.

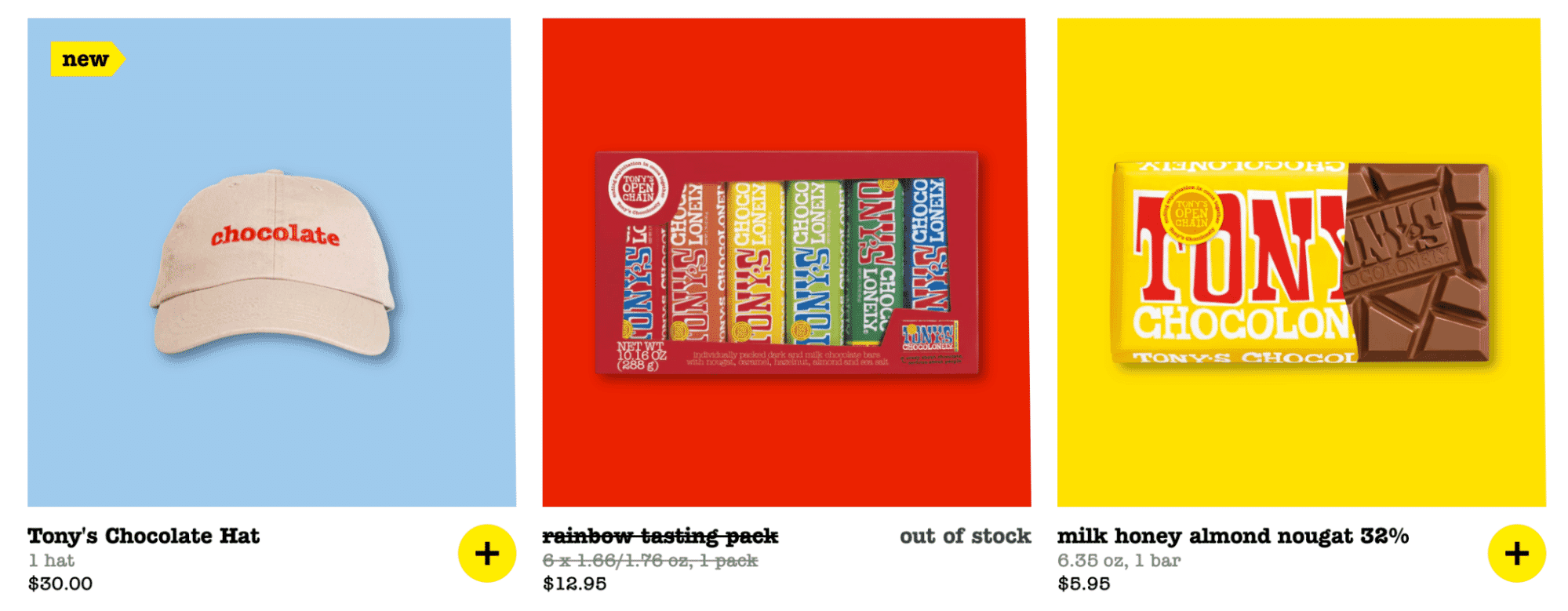

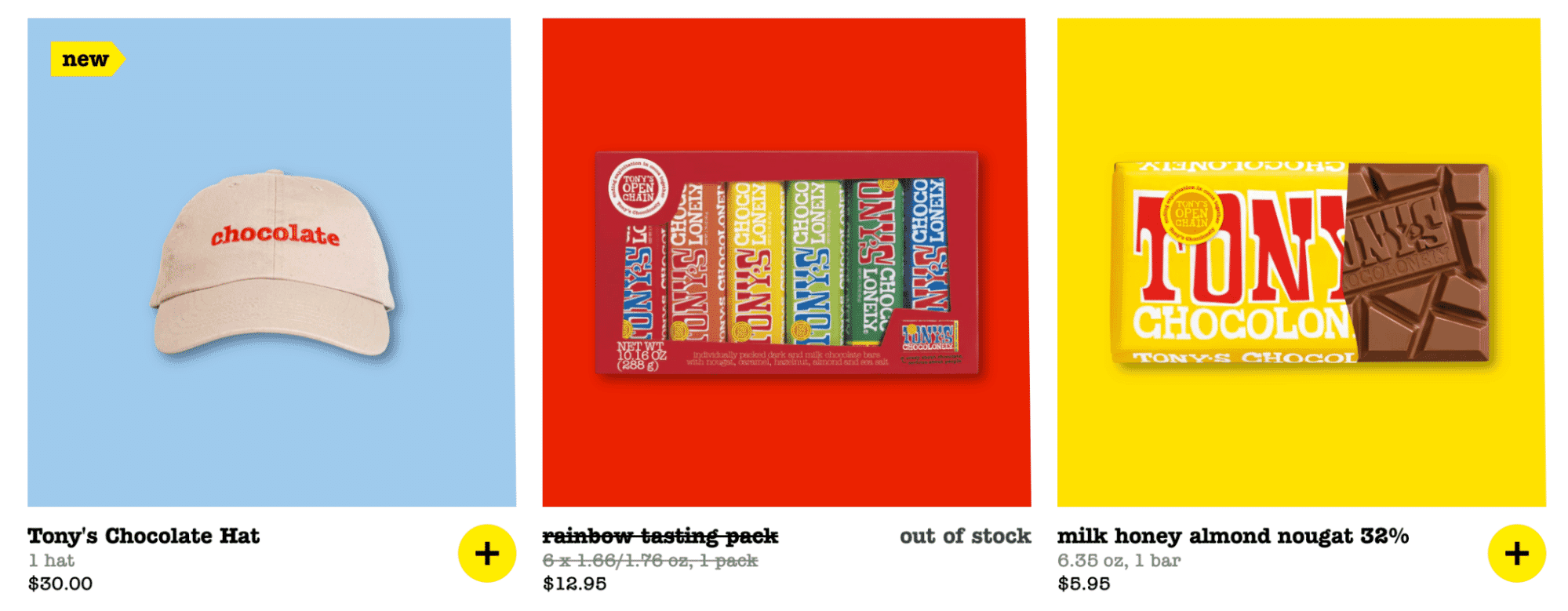

49. Tony’s Chocolonely

Image source

Tony’s Chocolonely brings the same bold, joyful energy of its packaging into its product photography. Vibrant, solid-color backgrounds create instant visual impact while keeping the focus squarely on the products. Items are shot straight-on with clean clipping paths and slight shadows to create a floating effect, lending a sense of playfulness and modernity. Every shot is bright, color-blocked, and punchy enough to pop in any feed or grid.

50. Ghia

Image source

Set against a creamy, sunlit backdrop, Ghia combines perfect product symmetry with unexpected moments—like a pour shot mid-air or cans balancing precariously on glassware. The lighting is soft yet directional, giving glass and liquid a gentle glow while letting label colors pop with vintage flair.

Create your perfect product photos

Great product photography doesn’t just capture what you’re selling—it captures why someone should care. Across industries, from fashion to food to tech, the most successful ecommerce brands use thoughtful visuals to build trust, spark desire, and drive conversions.

If you need help making your own photos stand out, we’re here to help. From background removal and retouching to full-on image enhancements, our team can take your product photos from functional to phenomenal.

Ready to elevate your product visuals? See how our photo editing services work and get started transforming your images today.