[ad_1]

We had the pleasure of chatting with Kaya & Blank about their latest project, Intermodal. Their salted prints don’t dramatize—they speak with crisp, architectural clarity. Paired with the nighttime footage of shipping ports, their work turns industrial sprawl into a sensory, mesmerizing experience.

Heidi: Intermodal captures monumental operations in a minimalist way. As photographers, how do you decide when to let scale speak for itself versus when to intervene with framing?

Kaya and Blank: We tend to approach these sites with a sense of stillness rather than trying to dramatize them. The scale of the ports is already overwhelming, with endless cranes, container stacks, and ships, so often our role is simply to frame the scene in a way that allows the scale to register without distraction. At the same time, we think carefully about vantage points, how much of the surrounding environment is visible, and how the image is layered. Sometimes bringing in an extreme close-up, like the corner of a container and the dust it expels when being stacked, or a tight shot of the cable systems that, when looked at closely, resemble waves, can shift the way a viewer reads the space.

When we first started filming for Intermodal, we were not able to film much that made us feel truly excited. After several nights of filming and reviewing the footage, it felt like something was missing. We eventually decided to invest in an extreme telephoto lens, and that completely changed the perspective. The way the lens compresses distant layers became the perfect visual equivalent of what ports do to the world; they collapse space. And once we found that look, the video component of Intermodal really began to take shape.

We do not usually think in terms of narrative when we edit, but we do work toward a sense of flow. The video is shaped with certain key points, like a beginning and an end, and the end point often defines how the structure unfolds. We think in chapters rather than isolated scenes, allowing each segment to develop its own tone and rhythm while still being part of a larger whole. The connections between these chapters are built visually, through echoes of motion, color, or atmosphere, rather than through plot, inviting viewers to navigate and assemble their own experience of the work.

The Port of Los Angeles can feel like a fortress, especially at night. Were you surprised by how much access you were able to get?

Yes, absolutely. The first time we filmed in the ports was actually for our previous project, Crude Aesthetics. There are several oil derricks inside the port area, and that is what first brought us in. While it is true that most of the port is inaccessible, there are public parks, waterfront walkways, and fishing piers tucked inside the industrial zones. Over the two years we worked on Intermodal, we returned to some of these spots again and again, usually in the middle of the night, to capture the operations. Over the course of two years, we only ran into access issues once, which is remarkable given the scale and security of these sites.

Photography has always been about light transforming matter. Your processes range from bitumen to salt and UV light. How does your process push against the digital era?

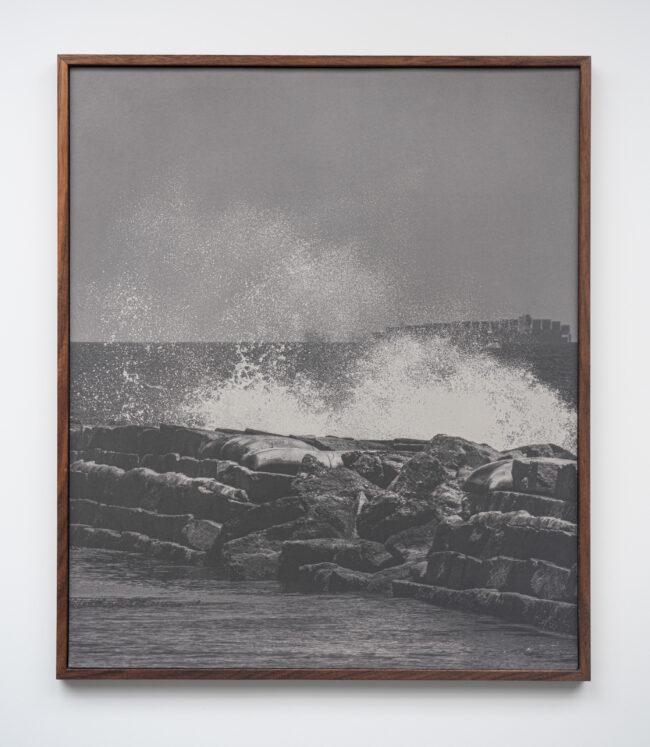

Our interest in these processes come from making the materiality of the image part of the work. Historical processes like heliography (bitumen) and salted paper printing remind you that a photograph is not just an image, it is a physical object shaped by chemistry, light, and time. Each print can have unpredictable qualities, shaped by the environment and the materials at hand.

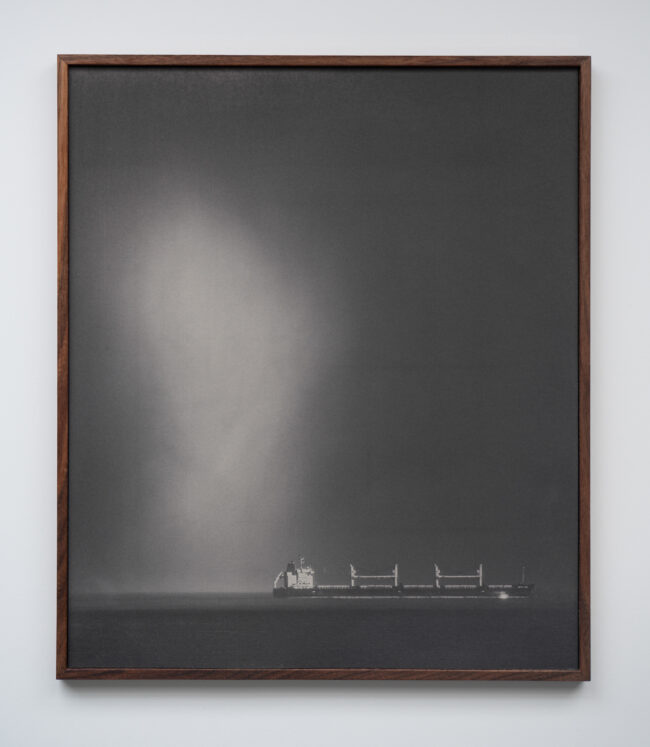

Filming digitally and creating photographic objects require two completely different modes of engagement. All of our video work is filmed at night, while the photographs for the salted paper prints are taken during the day. In a way, that separation echoes the relationship between digital and analogue, they are as different as night and day, yet part of the same cycle, and together they form a more complete picture of the subject.

19th-century salt prints were about light, time, and trace minerals. Your salt prints were created using water collected from the Port of Los Angeles. How did the chemical or environmental qualities of that water influence texture and unpredictability of the prints?

The port water definitely had an influence. It carries sediment, minerals, and pollutants that interact with the chemicals in subtle ways, sometimes creating speckling, sometimes altering the tonality. It is not something you can fully control, which is part of the appeal.

When we first started working with salt prints, we tried dipping the paper directly into the port water. That much salt built up in the fibers created results we did not enjoy, the images lost too much contrast and sharpness. It became a back-and-forth question, how much of the site do we let into the process, and how much control do we want to keep? We eventually settled on brushing the port water onto the paper in the studio. That gave us a balance we liked, the physical presence of the place still embedded in the print while making it light sensitive, but with a lot more clarity and contrast.

How did using your still photography embed movement into a transient subject?

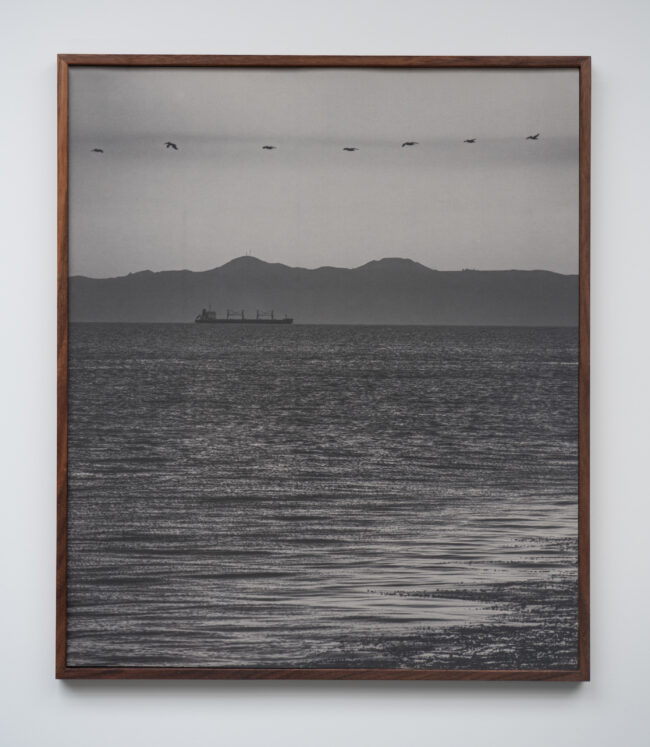

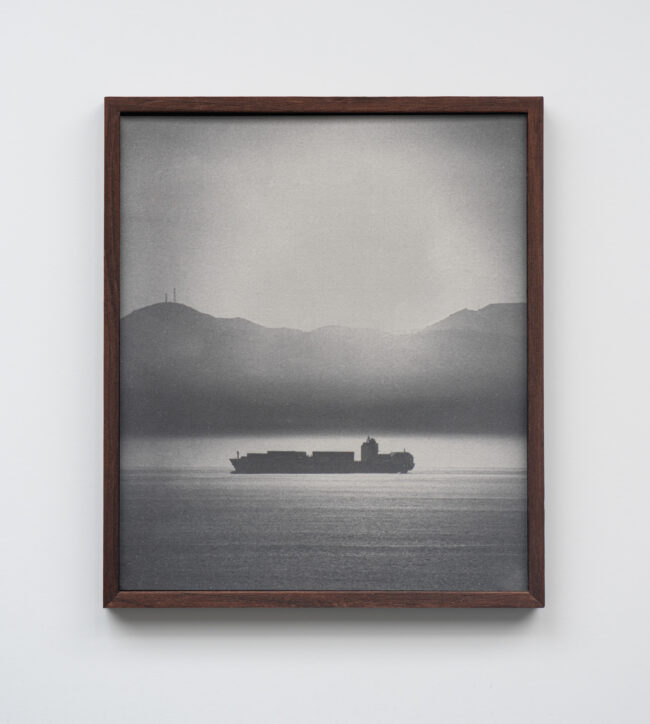

The installation is divided between the video, which shows the intermodal operations of containers being loaded and unloaded up close, and the salted paper prints, which return the focus to the land, or rather, the seascape. The video places you in the midst of a giant machinery, surrounded almost entirely by containers, cranes, and movement. The salted paper prints reverse that perspective. The ships become distant silhouettes on the horizon, and attention shifts to the environment in which they operate.

We aim to balance formal qualities in our installations. Working with both moving image and still photographs allows us to focus on different aspects in each. While the video exists only as light projected onto a surface, the prints have a tangible presence in space, their textured fibers, weight, and scale create a physical encounter that the immaterial image cannot. This difference in materiality shifts the viewer’s experience from an enveloping, ephemeral flow of movement to a slower, tactile engagement. The salted paper prints share the same aspect ratio as shipping containers, and some are divided into stacked segments that echo the appearance of how containers are organized on ships and in the ports.

The ports are powerful symbols of global commerce, efficiency, and environmental cost. How do you balance creating visually compelling images with raising critical questions about our complicity in these systems?

We do not think those two aims are separate. The beauty of the port at night, the lights, the scale, the choreography of movement, is part of its seduction. At the same time, we are aware that all of this efficiency is tied to systems of extraction, exploitation, and environmental damage. We try to present the images in a way that allows both responses to exist at once, the fascination and the unease.

Art can be a space for ambiguity, and that is something we value, especially with complex topics like global trade and our own roles in a consumer society. We do not want to offer one-dimensional answers, instead, we would rather make work that leaves room for viewers to sit with conflicting impressions. That complexity feels more honest to the way these systems are experienced in real life.

The endless movement of cargo can be both awe-inspiring and anxiety-inducing. What was your hope for viewers to feel when engaging with your work?

We do not expect everyone to feel the same way, but we hope viewers take the time to really look. The work is not meant to deliver an instant message; it is more about creating space for sustained attention. For some, the scale and complexity might inspire awe. For others, the relentlessness of the activity might spark discomfort or questions about what drives it.

After the opening, someone told us that the video felt very visceral, and that for the first time they might have experienced something close to megalophobia, the fear of large objects. That reaction stayed with us, because it is exactly the kind of physical, emotional response we hope the installation can create. If the work can hold that duality, fascination and unease, then it is doing what we intended.

[ad_2]

Source link

دیدگاهتان را بنویسید